EVENING WILL COME: A MONTHLY JOURNAL OF POETICS (ISSUE 19: JULY 2012)

Noah Eli Gordon

from Dysgraphia

My mother tells me a story. I was saving your name. It was going to be your older brother’s but I was afraid it might be a curse. A book by Josh Greenfeld, A Child Called Noah, gave me the idea, but that Noah was autistic, so I used Josh instead. He turned out fine, and we gave you the name. You were two or three months old when I took you to see your grandparents in Lexington, Kentucky. I was alone, holding you in my arms, when something on the bookshelf caught my eye. The Rabbi by Noah Gordon. “Oh no,” I said out loud, pointing to the book, suddenly crestfallen. Everyone ran into the room. I asked if anyone knew about this. I asked if I knew about this.

*

My mother writes my name with nail polish on a lunchbox. The applicator is imprecise, smearing a few letters. We eat lunch on the playground. Afterwards, someone points at the box. Who’s Nola Gordox? He’s the river monster, someone else says. Run! Here are the rules to the Nola Gordox River Game. All of the woodchips are lava, a river of lava. If you step in it for more than ten seconds you burn to death. Nola Gordox lives in the lava. If he grabs you you’re dead. There is no loitering. If you’re standing on one piece of equipment for too long you’re dead. Too long is too long and you’re dead. You have to move across the river and all around the jungle gym or you die. The game lasts until recess is over or everyone is dead. You can’t kill Nola Gordox. No one can.

*

I am part of an error at the Forbes Library in Northampton. Wait, I have a fine on my card? But I don’t even have any books out. Nope. No. I never checked that out. Yes. Yes, I’m sure; I’m positive! Uh huh. Yes. Yes, Noah Gordon. N-O-A-H G-O-R-D-O-N. No, I live in Northampton, just down the street. Oh, okay. Well, that makes sense. I guess there are a lot of us out there.

*

The famous poet tells me a story. A more famous poet was at an award ceremony with the most famous poet. The most famous poet told the more famous poet that he felt like a fraud. The more famous poet told the most famous poet that we’re all frauds. Months passed. I thought about this story often. Although the details were masked, everyone was given pseudonyms, and the events were allegorized, when the more famous poet published a new book, I recognized immediately this story in one of the poems.

*

It was lunchtime. My sandwich was peanut butter and jelly—two pieces of perfectly intact bread. I was baffled. How could I eat this? Why hadn’t my mother cut my sandwich? The teacher told me to get a knife from the drawer and do it myself. There are three instances thus far in my life of a concentration so extreme on a single image that I can recall it with photographic detail: the hour I spent watching a spider spin an entire web outside of my front door; standing in front of Van Gogh’s L'église d'Auvers-sur-Oise until my own breathing seemed to be that of the woman in the painting with her back turned toward me; and the wholeness of this sandwich, obscured only by the white, plastic knife I dare not move.

*

In 1906, William Elvis Sloan founds the Sloan Valve Company, selling exactly one Royal Flushometer, his newly invented valve system for urinals, intended to replace bulky toilet tanks. The following year he sells two. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp creates Fountain, a urinal turned 90 degrees, and signed “R. Mutt 1917”. Duchamp submits the piece under this pseudonym to an exhibition, where it is ultimately hidden from view during the show. Every time I’ve looked at the metal valve above a urinal, I’ve seen the name Sloan etched somewhere on its surface. Although Duchamp’s original Fountain was lost, replicas he’d commissioned in the 1960s are still on display. Sometime in the 80s, my grandfather tries explaining to me the workings of the stock market. If I had the money, I could think then of only two companies whose stock I’d buy: Nintendo and the Sloan Valve Company. In 1990, we move into the house on Cassia Terrace. The bathroom closest to my bedroom, the one I use most often, has a shower with a sliding door, which is perpendicular to the toilet. A metal bar runs horizontally along the door’s midpoint. I rest my hand there whenever I take a leak. In 1993, French performance artist Pierre Pinoncelli urinates into a copy of Fountain. This same year, I am standing at a urinal in a busy restroom, men to my left and right, several others in line behind us, when, suddenly, I realize I have developed a habit, a crutch; I have to touch something metal before I can piss. Normally, I’d tap the handle above the urinal, but the act would no doubt appear odd, and in such cramped quarters I don’t want to risk it. In 2000, Chinese performance artists Yuan Chai and Jian Jun Xi may have urinated in the Tate’s copy of Fountain. Six years later, Pierre Pinoncelli takes a hammer to the Centre Pompidou’s copy of Fountain. Today there are millions of Royal Flushometers in use around the world. According to their website, the Sloan Valve Company is privately held and family-owned. I’m looking down. My fly is open. The restlessness of the line behind me is overwhelming. I’ve developed a method. I tap the zipper, touching metal.

*

I’m seventeen. It’s a few weeks before our first show, the first Bingomut show. I can’t sing, but that’s what I do. I’ve been practicing in my room, practicing along with an Iron Maiden tape, not because we’re a metal band, but because their singer, Bruce Dickinson, is nearly operatic, and I think it might help me learn to push sound out from somewhere deeper than my mouth. I don’t tell anyone I’ve been doing this. We’re a punk band, a punk-ska band, and such an admission would no doubt be followed by gratuitous teenage ridicule. The guy at the tattoo shop asks me how old I am. Eighteen, I say. After he tattoos the griffin on my calf, he asks me how old I really am. Eighteen, I say, again lying. The griffin is done in black ink, and so irritates my body that for weeks it looks red. We share our warehouse with Marcus’s brother’s band. A few days before our show together, they’ll name themselves Puddle, but for now they’re called Fudgie the Whale, a kind of ice cream cake and also a joke about the FTW tattooed on my shoulder. What I can’t figure out is why my mouth is filling with sores. They’re lumpy and irritating, covering the inner skin of my lips. I know there will be hundreds of people at our first show—and there are. The next day the sores are gone. When another band forms at our high school, they decide to call themselves Noah’s Red Tattoo.

*

During the car ride, my father tells me a joke to pass the time. The joke requires a lengthy exposition. It is, in fact, all exposition. Johnny is a good boy. On his fifth birthday, his father allows him to decide on a gift, any gift, anything he wants, anything at all. Johnny wants 1,000 purple ping pong balls. He refuses to tell his father why. Okay Johnny, okay. So be it. For each subsequent birthday, my father repeats this exchange, modifying it slightly. Here and there the father pleads; you’re sixteen now, what about some wheels? Now that you’re eighteen, something a bit more grown up? Johnny’s desire is firm: 1,000 purple ping pong balls. Five minutes go by. Ten. Twenty. We pass fields, bridges, long brick buildings, intersecting highways. “In the structure of the Time through which life moves,” writes Paul Valéry, “are curves leading imperceptibly from the impossible to the real, from the unthinkable to the achieved.” The sun dips lower, is bounced back at us from the rear windows of the cars ahead. My father is still talking. It’s Johnny’s birthday again. Again, the ping pong balls. The joke ends with Johnny being struck by a car, his father rushing into the street, lifting his son’s head, and asking for an explanation before the boy’s inevitable death. I just… I just… I wanted them because… Of course, the boy dies before he can spit it out. The unthinkable is achieved. With this narrative, we have driven dozens of miles. Like the ancient Greeks, the Aymara people of South America conceptualize the past as being ahead of them and the future behind. That the joke goes nowhere is not entirely true.

*

My middle school Spanish class is a nightmare. I can’t spell. I can’t pronounce the words. I can barely summon enough attention to look in the teacher’s direction, let alone listen to whatever it is she’s saying. An episode of the 80s sitcom Growing Pains I’d seen only once remains with me. Cocky slacker Mike Seaver, planning to cheat, writes on the soles of his shoes. As the test is administered, he doesn’t look at them; answers are coming with ease. The mere act of copying allowed him inadvertently and unknowingly to learn the material. Stretching out after the test as a self-congratulatory gesture, he kicks up his feet—the laugh track peaking when his teacher sees the bottoms of his shoes. The obvious moral here is about effort; however, for me it is one of ingenuity. Shoes are just too risky. I copy vocabulary words onto a small piece of paper, folding it over and over until it’s the size of a quarter. I hide it in my palm, manipulating its tiny geometry with a thumb. There is something surgical and tender about the act. I am caring for the world’s smallest animal. Afterwards, I eat the paper.

*

Travis sends me the manuscript of his novel. I am in love with it. I am in love with him for writing it. Although it’s fiction, much is autobiographical, and I recognize people, stories, etc. About midway, there is a scene in which the narrator’s step-father smuggles cocaine onto an airplane in the hollowed-out sole of his boot, which eventually dislodges, spilling the powder on the plane’s floor. We are in Wichita, Kansas for the opening of the Poets on Painters exhibit. It’s the first time in years that we’re all together, laughing, drinking, swapping stories at Katie’s apartment late into the night. Paul tells us about his step-father, how he was trying to figure out a way to smuggle some cocaine into the country. I bet he put it in his shoe, I say, looking over at Travis, and the devilish grin engulfing his face. Did I tell you this before? Paul asks.

*

I wasn’t yet old enough to grow a beard, nonetheless, there, in the mirror the unmistakable shape of a close-cropped goatee. I step closer, lean into my reflection. Small red spots speckle my chin. In a week, they will disappear. Perhaps this is puberty. The book about what happens to a boy’s body given to me by my mother is no help. Every few months, the semi-circle of spots returns. Fades. Returns. Each time, I catalogue my actions and eatings, but there is no discernable pattern. This continues for years. In Classical antiquity, women and prepubescent boys were awarded with fake beards for performing acts of wisdom and courage. One afternoon, in front of the TV, finished with my soda, I rest my chin on the glass, and begin absently sucking it tighter to my face, a habit whose slow perfection had failed, until now, to make my catalogue. This realization is my first act of wisdom.

*

I have been trying to write this paragraph all afternoon. It should have been simple. It’s a story I’ve told hundreds of times. Normally, it goes like this: I’m watching Raiders of the Lost Ark on TV. I’m ten, maybe eight, or twelve. Marion Ravenwood is wearing a white dress, low-cut in back. There is a pillow underneath me which I am grinding against. My father walks into the room, sees what I’m doing, and lets out a loud, bellowing belly laugh. Instantly, I am overcome with embarrassment. I was just bouncing, I tell him. Here are some facts: in telling this story, I’ve never used the word grinding. Karen Allen played the role of Marion Ravenwood, the spirited love interest of Indiana Jones. For the scene in which she is held prisoner by Dr. Rene Belloq, the unethical, French archeologist played by Englishman Paul Freeman, she was asked to come up with a reason why Ravenwood might accept her captor’s suggestion to change into the low-cut white dress. Allen decided that her character would do so in order to conceal a knife within the blouse she removes. I was not overcome with embarrassment, rather it was with shame. Shame is the other side of the erotic. It is not the erotic being seen, but the aftermath of one caught looking. Belloq watches in the mirror as Ravenwood is changing. Her back is to it. Her blouse, already off. She unhooks her bra, sliding the dress over her head just before the scene cuts.

*

Large. Considerable. Extensive. Significant. I am taking my homework assignment seriously. Great. Sizable. Huge. Massive. I am in the fourth grade. Mammoth. Heroic. Colossal. Voluminous. I am disarmed and enchanted. Super. Monstrous. Humongous. Herculean. I have never before felt so singularly engaged in any task, so free of myself. Oversized. Substantial. Whopping. Spacious. I am bewildered by the thesaurus. Monolithic. Cosmic. Astronomical. Jumbo. I am aware, a part of some importance, an integer. Pregnant. Prominent. Conspicuous. Awash. This is the same year in which I will be locked in a small room all day, later suspended for swearing at the school secretary. Bulky. Extreme. Staggering. Sizeable. This is the same year in which the principle will bring a week’s worth of homework to my front door, in which I will be enraged at her appearance, open it, leap into the air, and land an uppercut, sending her and the stack of books to the ground. Incalculable. Roomy. Magnanimous. Galactic. This is the same year in which I will be expelled from the public school system. Mountainous. Elephantine. Hulking. Giant. Tonight, I am supposed to find ten synonyms for big. Developed. Ripe. Vast. Grand. Tomorrow, I will turn in eighty. Behemoth. Cyclopean. Pythonic. Prodigious.

*

My brother has taught me a chant, a string of words with an incantatory rhythm, but whose meaning escapes me. Mother fucking titty sucking booger ball bitch. Mother fucking titty sucking booger ball bitch. He leads me from the asphalt parking lot through the double doors of the school’s side entrance, pushing them open with his back. I’m an instrument. Mother fucking titty sucking booger ball bitch. Keep going. Keep going. He continues to face me, taking tiny reverse steps. I’m an orchestra. Mother fucking titty sucking booger ball bitch. I’m six years old. He is ten. Twenty five years later, he’ll tell me that because of its tonal system, a single word in one of the Chinese dialects repeated with slight differences of inflection can be translated as: poem is shit. Mother fucking titty sucking booger ball bitch. I follow him down the hall, through another set of doors, into the crowded waiting area of the principal’s office. Mother fucking titty sucking booger ball bitch. Everyone’s staring at me. I am inflated with pride.

*

I can’t get over/ how it all works in together.

—James Schuyler

There he is again. I see him everywhere in Northampton, coffee shops, movie theaters, convenience stores. I even saw him in Brattleboro. He’s at every jazz show in town, actually snapping his fingers. We saw him once wearing socks with tiny embroidered Eiffel Towers, so that’s the nickname Eric gave him. Eiffel Tower Socks looks at me. It’s that cat Shawn, he says. No, wait, you’re not Shawn. You look just like this cat Shawn. In Killzone, a first-person shooter for the PlayStation 2, the Interplanetary Strategic Alliance battles the Helghast Empire. ISA members are human, while the Helghast cloak themselves in a gasmask-like contraption which turns their eyes into glowing red orbs. Here and there, buried in the landscape, there are bits of debris that look similar: two red dots on a rock; crimson stains on a distant doorframe; a tattered poster in a subway terminal. They’re purposeful distractions, meant to draw a player’s attention away from the enemy. There’s one, I tell Eric, pointing to the left of the screen, where what looks like a Helghast soldier is crouched behind some trees. Eric zooms in. It’s just the sun making a bit of pink though a few branches. It’s that cat Shawn, Eric says.

*

To mark the beginning of my formal Jewish education, I am consecrated at Brith Emeth Congregation in Cleveland, Ohio. I am seven, restless, shuffling my feet, unable to stand still for the photograph my mother and grandparents want to take, their frustration increasing my own, until I tear in half the miniature Torah I’d been given, an act which marks the end of my formal Jewish education. Ten years later, in the car headed somewhere unimportant, my mother reminds me about the act. Although I remember it differently, she says I was upset that my father wasn’t there. Jim Croce’s “Operator” comes on the radio. We both love this song. It’s about a jilted lover wanting to reconnect, to let his girlfriend know that he’s okay with her having taken up with his old best friend. Eventually, he gives up, deciding it’s better not to rekindle communication. My mother says the song reminds her of Josh, my older brother. She says the song’s about a parent learning to let go of a child. She’s wrong, but so am I.

*

I call the Emily Dickinson Museum. I’m connected to an elderly woman who wants nothing more from the moment I begin speaking than to get rid of me. She tells me there is no key. Thank you. Goodbye. No, no diary. She hasn’t heard of anything like that. Goodbye, thank you. Goodbye. I’m sure she’s wrong. She has to be. I half-heartedly search online for a list of the museum’s contents. There are thousands of hits. Replica of the white dress. Replica of the piano she played into adulthood. Replica of the white dress. Small writing table, much like the original. Franklin stove. Mahogany bed. White dress. Small clock and basket atop her dresser. The dress. Some pictures show the basket resting on the windowsill. Some show the clock on the nightstand. There’s a blue bound hardcover book on her dresser. There’s the dress again. 20 years ago, returning from a field trip to the Dickinson Homestead, my friend pulls a small key from his pocket, cups it his palm, hiding it from everyone’s view but mine. It was from her diary, he tells me. When no one was looking, he stepped over the roped-off area and swiped it. Before I called, I thought we’d have a laugh or two over the box of replicas kept in the backroom, ready to assuage the juvenile antics of each week’s worth of forced school outings. But this woman tells me there is no key, no diary. My instincts tell me she’s wrong. Dickinson agrees:

Recollect the way—

Instinct picking up the Key

Dropped by memory—

*

I’m curt, reserved, emanating nothing more approachable than a brick wall, a defensive technique perfected over the two years I worked selling jewelry from an outdoor cart in Boston’s Downtown Crossing. It’s a necessary masonry. A brick wall for the junky nodding off while fingering a pair of sterling silver hoop earrings. A brick wall for the teenager trying to palm the new Nike ring. A brick wall for the endless stories of the veteran’s instant and unwanted friendship. A brick wall for businessmen, for drunks, for European tourists in tight shorts. And especially for this guy. He has my glasses, my shoes, the same sort of shirt I’d wear, the same full sleeve tattoos. Didn’t Shelley meet his doppelganger before drowning? He asks me if I was at the show last night, asks me what I thought, something about seeing me around. I’m giving him the wall, a really thick one at that. Okay, man, good to meet you, he says. By the way, what’s your name? I’m Shawn.

*

There is a message in the inbox of my new facility email account from my father, whom I haven’t spoken to in years, but who is eagerly anticipating our upcoming reconciliation, which I’m learning about for the first time. I never knew him to use the nickname Mickey but it’s close enough to Michael. Because this is such an odd and oblique way to initiate contact I don’t write him back. I cried the first time I read Raymond Carver’s story “The Compartment.” Myers, the protagonist taking a train to meet his son for the first time in eight years, upon reaching the station, decides he doesn’t want to see him after all, and slinks down in his seat, relieved he’s unable to catch a glimpse of the boy from the window. I wasn’t upset with Myers’s decision, but with the sudden empathy I had for him; I understood this man and it was maddening, an unwanted catharsis. The emails continue. After a few weeks, it’s clear that I’m not the intended recipient, although I’m beginning to feel something for Mickey’s situation, and the desperation with which he wants to connect to his son Noah. In my first response, I tell him as much. He replies thusly:

From: Mickey.Gordon@XXXX.XXX [mailto:Mickey.Gordon@XXXX.XXX]

Sent: Sun 9/10/2006 11:47 AM

To: Gordon, Noah

Subject: RE: Trip

I apologize for burdening you with these e-mails. Obviously from my messages, I

have been sending them to my son, whose name is in my contact list and also is

Noah E. Gordon. For whatever reason, my e-mail has been selecting your address

(within the global address book) preferentially over my contact list. I will try to

make sure that the problem does not continue (which will probably correct my

apparent failure to contact my son when I thought I was doing so).

Thank you.

Mickey Gordon

*

Hi, this is Noah Gordon, I’m calling to get the room number, I say. My armpits are already damp. It’s the first time I’ve worn this suit, neck tie, new shoes—the whole nine. Hel)o, Noah th% roo& !s @83%. Sweat runs down my sides. I’m sorry, but I’m having trouble hearing you, I say, confused by what I thought were four numbers when my own room there had only three. I’d already met the famous poet on the other end. There’s a pull-quote from a review I’d written on the back of his collection that won the National Book Award. My name’s not there, but I feel a kinship nonetheless. He says the number again. Okay, I’ll see you shortly, I answer, hanging up. Wait, I’m not sure I heard him correctly. 3584? I write it down, look at the white phone, walk off toward the bank of elevators. 3584 or 3854? or 3458? Now, I’m really nervous. I take the elevator to the thirty-fifth floor. I didn’t know this building was so tall. There’s the room. 3584. I’m five minutes early. If this is the wrong suite, I’ve got time to get up to the thirty-eighth floor or down to the thirty-fourth. But not both. This realization kicks my sweat glands into overdrive. I knock.

*

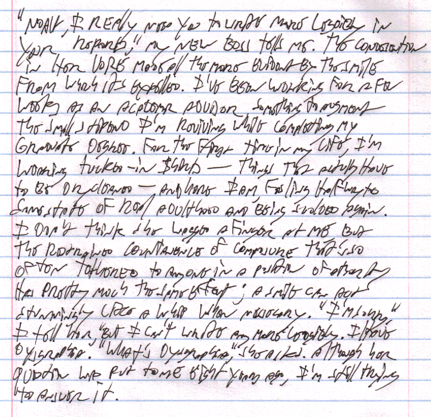

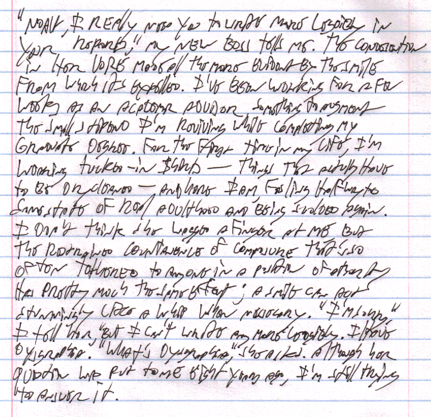

From Error to Error: on Dysgraphia

My relationship to language is an overdetermined, tangled mess: the end result of unequal parts—learning disability, educational deficiency, and self-stylized coping mechanisms. Although I write through it everyday, I’d never considered writing about it until late in the summer of 2007. The novelist Selah Saterstrom sent around an email asking friends to share a brief story with her. She was going through a period of grieving, unable to write, yet overcome by the necessity to engage with stories, even other people’s stories. My writing life thus far had made little room for the purely autobiographical. My mother once asked when I was going to write one of those poems that tells a personal story, like the ones she hears on NPR. My answer was simple: Never. Of course, I was wrong. I sent Selah the following paragraph:

The gutters on the house were dented and old, so clogged with leaves from last autumn that they drained by spilling water over their sides. In later months, they grew huge icicles, a row of teeth surrounding the house. My brother and I would toss snowballs, try to knock them down. Mostly, they shattered as they fell. Sometimes the pieces were salvageable. I took the foot-long tip of one of these and put it in the freezer. I suppose I wanted to commemorate something. Later, I tried to eat it. My lips stuck on its surface. What I didn’t know: put your head under the tap and run the water; it’ll unstick. Instead, I pulled. The first layer of skin from my lips remained on the icicle. It looked like a kiss. I touched my mouth, moved my hand away. There was blood everywhere.

After this paragraph, I wrote another, and another, until there were dozens and I realized I was actually writing a book. Because so many of these paragraphs were built from the anecdotes and ephemera of my dedication to language and its collision with the errors associated with a peculiar learning disability that I have, I decided to name the book after the disability. Dysgraphia is a work-in-progress, which will be composed of autonomous paragraphs that circle around moments of awe at the discovery of the potential of expressive subjectivity, and then dread at the actual difficulties of inhabiting that expression.

The OED defines dysgraphia as an “inability to write coherently.” What sort of coherence is this? What does coherent writing look like? What does coherent writing read like? Barthes, justifying his tendency to employ fragmented brevity, quotes from André Gide: “incoherence is preferable to a distorting order.” In Canto CXVI, Pound pulls down his own vanity with the admission, “I cannot make it cohere.” Obviously, one can write without coherence; one can orchestrate constituent parts without making explicitly clear the relation of each to the whole. This is nothing new: the palimpsest, the Book of Hours, the collage. As the art critic Meyer Schapiro notes, “Distinctness of parts, clear groupings, definite axes are indispensable features of a well-ordered whole. This canon excludes the intricate, the unstable, the fused, the scattered, the broken, in composition; yet such qualities may belong to a whole in which we can discern regularities if we are disposed to them by another aesthetic.” Didn’t the Modernist epoch teach us that coherence is a fallacy?

But this is structural coherence—the supposed unity of content and form, part and whole: line, stanza, sentence, paragraph. The relationship of dysgraphia to coherence is rooted in the creation of individual letters and words, in a graphing impairment. Those of us who suffer from dysgraphia are predisposed to problematizing the signifier and the signified, to Schapiro’s above-mentioned other aesthetic, if only pictorially, in the scattered, broken, and unstable composition of our handwriting. So, the OED definition lacks the requisite specificity. In fact, its entire definition reads: “Inability to write coherently (as a manifestation of brain damage).” While it may be true that brain injury or trauma can lead to the onset of dysgraphia in adults, some of us are born with the condition, whose actual origins are unclear.

My birth was induced with pitocin, a synthetic form of oxytocin, the naturally occurring hormone that causes uterine contractions. Although it is commonly used to aid deliveries, it is also known to potentially reduce oxygen to the baby. My mother tells me that the moment she was given the injection she was gasping, unable to take in a breath, and was given another drug the doctor told her would slow down the effects of the pitocin. The delivery was further complicated by the use of forceps, which left an enduring scar on my cheek. I don’t mean to overdramatize my own birth, only to point out its potential link to my learning disability.

The problem with dysgraphia as a term is that it’s lexically and etymologically misleading. Dysgraphia doesn’t mean an inability to write; rather, it indicates a neurological issue that manifests itself as a deficiency in one’s writing. I’m 34 and have published several collections of poetry, as well as dozens of reviews, and essays. There is no inherent incongruity in a prolific writer who suffers from dysgraphia. In navigating grammar, syntax, spelling, and the motor functions associated with forming letters, one simply has to work differently.

For example, as I type this essay into a Word document, dozens of red squiggles appear underneath numerous misspellings. In the paragraph above, I’d written entomologically rather than etymologically. Sometimes, it takes me upwards of ten minutes to come up with a spelling that matches closely enough my original intention so that I might be able to click on the correct choice. When I write even a micro-review, say 300 words long, it can take me a few hours to normalize my prose. Handwriting presents even more difficulty, as mine is often illegible, switching haphazardly between upper and lower case letters—textbook symptoms associated with dysgraphia.

It’s not the symptoms that make writing difficult; it’s their distortion of the expressive impulse. “Dysgraphia can interfere with a student’s ability to express ideas,” notes The International Dyslexia Association on one of only a handful of websites that doesn’t recycle the same information on the subject (www.interdys.org). “Expressive writing requires a student to synchronize many mental functions at once: origination, memory, attention, motor skill, and various aspects of language ability. Automatic accurate handwriting is the foundation for this juggling act. In the complexity of remembering where to put the pencil and how to form each letter, a dysgraphic student forgets what he or she meant to express.” As any writer knows, the lag time between a thought and its written articulation can be an annoyance. For those with dysgraphia, it’s often monstrously debilitating.

My diagnosis came only about a decade ago, as an undergraduate on the verge of dropping out because of my inability to complete the foreign language requirement. I stared for hours at Spanish vocabulary words and still was unable to pronounce them. A school counselor suggested I take a battery of tests for various learning disabilities. Nearly ten hours of testing resulted in a 22-page document, which I keep in the top drawer of my writing desk. This report gave me an exemption from the foreign language requirement, but it didn’t answer all of my questions about the origins of my difficulties with expression.

Unable to tie my own laces, I wore Velcro shoes until the fourth grade. I stopped skateboarding in the eighth grade because, unlike my friends, I couldn’t figure out how to ollie—the aerial leap that’s foundational to any further tricks. I was never any good at video games, pool, bowling, anything requiring hand-eye coordination. I learned how to drive a car when I was 25. But what do these deficiencies have to do with writing? Aren’t they simply indicative of some sort of lapse in cognitive motor skills? Yes, they are—but so is dysgraphia. Dysgraphia itself lacks any solid, clear, universally recognized definition, and instead is discussed in tandem with other learning disabilities and disorders, often as an ancillary component of dyslexia or an additional complication arising from a stroke or other serious trauma. For one attempting to make sense of the condition, this is an irritable uncertainty.

The first moments of my realization that there might be something unusual about my engagement with language were colored with a kind of shame—a psychological equivalent to the computer screen’s red squiggles. I was in an undergraduate class taught by the poet Martín Espada. We were studying Neruda, and I volunteered to read a poem aloud. Although I can’t now recall exactly which poem, I know it was from the collection of Neruda & Vallejo edited by Robert Bly, because my copy of the book is covered in the corrections to Bly’s fanciful flights of translation Espada was always quick to point out. Things were going well enough. Moving across the lines and down the page, suddenly, I was startled. Here and there were words I could define, but couldn’t pronounce, couldn’t shape into anything sayable, couldn’t stop from just sitting there on the page, staring flatly up at me. These days, it’s a common enough occurrence in my own classroom, where I often help my students through multisyllabic roadblocks, but this was different. The shame I felt wasn’t at my inability to pronounce a word; rather, it was at the instantaneous, public realization that I read in a rather odd way. I don’t sound out words. I memorize symbols, making each word into an individual visual image that I then assign an auditory value while registering its referential significance. Sometimes these auditory values sound preposterously off the mark. As a child, I called “dogs” gwoggies, which is cute; as an adult, it’s not. A “dandelion” is not a dandy lion, yet, to this day I have trouble remembering so.

Here is a telling passage from the above-mentioned assessment document:

Mr. Gordon’s difficulties with reading phonology [ ] were evident on a task

of reading single-syllable nonsense words. He consistently mispronounced the

nonsense words that had a silent “e” at the end. Rather than altering the vowel

sound, Mr. Gordon pronounced the word as if the “e” were absent (e.g., “gare”

was pronounced as “garr”). On this task, Mr. Gordon obtained a score of 20/36,

which is equivalent to a third grade level. This phonological difficulty, most

likely, has an impact on Mr. Gordon’s experience of decoding, novel word

recognition, and reading rate with unfamiliar words.

I’ve developed a circuitous and eccentric system of phonetic cues for myself. Before I give a reading, or in preparation for a lecture, I’ll meticulously scan a text, fashioning in the margin my phonetic equivalent of any word with the potential to give me pause: ink-co-itly for inchoately; plue-tark for Plutarch; theo-low-gins for theologians. Interestingly, The Teachers & Writers Handbook of Poetic Forms uses a similar method, offering gems like “EL-uh-gee” and “ASS-uh-nance.” My own system embarrasses me. After a recent reading, I accidentally gave away one of my annotated books. I’m not sure who received that particular copy, but it must have been another poet, one I shamefully imagine scrutinizing and mocking my eccentric marginalia. As a participant in a poetics reading group in Denver, I try not to sit too close to anyone, fearful that a stray glance at the notes in my book might reveal this crutch.

On the 1987 the television show Star Trek: The Next Generation, Geordi La Forge, played by LeVar Burton, was born blind, and outfitted with a prosthetic visor that to most teenagers looked suspiciously like a banana clip spray-painted silver. This visor enabled him to see the electromagnetic spectrum. Before his stint as La Forge, Burton hosted Reading Rainbow, a children’s television show on PBS, which promoted reading through book recommendations, reviews, and celebrity appearances. For nearly a decade, I’ve carried in my bag a small device that my close friend, the poet Eric Baus, calls Geordi. Geordi is an electronic spellchecker. Does spelling have an electromagnetic spectrum? Without Geordi, I feel a kind of blindness.

In first grade I was enrolled in a Montessori school, where students from first through third grade were grouped together, and had three years to work through a sequence of educational rubrics. I put off phonetics. Unfortunately, by the time second grade rolled around, I’d transferred to a public school, where I found myself behind in numerous areas. Perhaps this compounded my future difficulties with language. A few years later, a sequence of behavioral issues led to my expulsion from the public school system. I was sent to Beach Brook School, whose website lists the following among its available programs:

• An intensive treatment unit for the most seriously disturbed children and adolescents

• Residential and day treatment for elementary through middle school-age children with serious emotional and behavioral problems

At Beach Brook, some of my classmates were dealing with much more serious afflictions, including severe obsessive-compulsive disorders and extreme autism. One boy, Tony, would have daymares. He’d be looking out the window, seemingly docile, then suddenly erupt in a bloodcurdling scream. This electrified the room, setting off a chain reaction of nuanced behavioral oddities among the other children, children who never spoke, children who couldn’t stop moving, children who, because of Tourette’s syndrome, suffered through an endless stream of profanities whenever they spoke. Education took a backseat to simple containment. Our classroom was a place to practice stillness and submission, not fractions or history lessons. The same was true when I was again institutionalized for nearly three years in high school, this time at a residential facility, as a consequence of numerous behavioral outbursts resulting from my inability to handle the public education system. Were the difficulties attached to my learning disability manifested in my behavioral problems? Were my issues with authority enhanced by dysgraphia? I can’t answer these questions. All I can do is write through them.

Selah’s solicitation was a gift. Out of her grief came my I’s unshackling. Having come to poetry in the shadow of the anti-expressive, post-confessional, fully problematized I, use of the monolithic pronoun has been for me fraught with anxiety—the ever-present fear of projecting a purely self-aggrandizing stance. Is my I worthy of exploration? Is my I really all that important? Is my I any different than others? These are questions I’ve embedded within my poetry, but the writing that precedes this essay is something different. As a disability, dysgraphia rendered my I illegible, untrue; as a writing project, Dysgraphia is an attempt to reveal it, an act of reclamation. Goodbye (for now), Je est un autre.

[this excerpt and its accompanying essay originally appeared in Fence Fall/Winter 2009-2010]

« home | bio »