1.

He forgot that, too.

We were sitting in the corner booth, my potato chowder going cold. Before me, his face bore another place and weather. I thought of Nevada, the desert stretch below the Chocolate Mountains, where I spent the days after the last time I’d said good-bye to him nearly a year earlier.

What I know about the desert I know by accident. On Route 6, overjoyed by solitude, I ran a curve, edging toward 100 mph, when the front right tire blew out. For a minute, I flew. And then, the abrupt landing, the airbags bursting open, the whirling voice of Joni Mitchell like a cliché of freedom getting beaten back by silence and an unguarded sun. Hours later, a state trooper would sit with me on the hood of my car waiting for a tow truck. The desert looks empty, ravaged, but in fact it’s chaotic with life. “See that lupine,” he said, “it’ll kill the sheep that eats it. And cows? Their calves come out deformed if they’ve got any in their system.” I looked for the lupine, noted desiccated stalks and low-dwelling succulents. I looked good and long as if the desert were a stop-action animation that, left unfinished, had stilled between winds. I thought I saw a sliver of shadow drop to the ground, or perhaps it was some tiny creature darting across the dust.

I looked at his face. It was not without gesture, though, like the desert, emotion seemed to fade before it could set. I wanted him to love me.

“You want me to come west, like you asked, or what?”

He didn’t say anything. He hadn’t ordered any food or coffee, so all he had was a cup of water. My question made no sense to him because he had no memory of what prompted it. He fingered the condensation along the yellow plastic, and then looked out the window where outside the snow was coating the city sidewalks.

I had never told him about my accident in Nevada, or the relief I felt immediately after the crash knowing I was truly alone and not merely abandoned. It had not occurred to me then that I could have died because running out of my car screaming “Help!” I was struck by indefatigable life. This was the opposite of what I had been feeling in the days preceding. I had been driving home from seeing him, though the whole time we were together he may as well have been somewhere else. We spent the days hiking the gentler peaks in and around the Sierra Nevadas, my steps indecisive and always behind his.

Driving home, it was foolish to take a route I didn’t know, a route that added a day to an already long trip, but I thought it was a way to be with him longer, even in the abstract, but now that I think of it maybe I was trying to understand my loneliness.

And I loved getting lost.

It’s not true that to live on so little is a gift. I still remember his face. He was so much younger then than I am now, but deep lines had already begun to form around his eyes. He spent so much time squinting at the sun. It was the one thing about him I knew perfectly.

2.

In every new landscape, I am struck by my ignorance.

Here are the words I’m gathering from this desert book: gravel ghost, indigo bush, spinystar.

It has been years since I’ve been in the desert. Today I live on a remnant prairie, where the snow falls consistently and does not stay.

I often struggle to discern the difference between what I remember and what I imagine.

A note in the grass explains.

I look up to see the winter grass, no snow.

How do I explain what I cannot describe?

As that white-haired gentleman said, “Without narrative a talent for description may as well be blindness.”

What am I to do with these images?

I see.

3.

The songs the state trooper played on his car radio whirred around us like the thriving highway Route 6 could never be.

In my memory, the songs have no words and I am relieved to be with someone other than the young man I’d just left. But perhaps there were many words. Perhaps the imprint of him hadn’t yet left me, as it doesn’t seem to have left me now, and perhaps I was wishing the state trooper were the young man I’d just left. I make him less important by explaining to a friend, years later, that what I learned from my past, if that is what I might call him today, is an appreciation for landscape. How, even as you behold the desert, you are made smaller by what you see. The late afternoon light striating against the rust-colored mountains, the shadows that keep betraying your perception of absence. Nothing is there, blooming.

The state trooper’s wife was expecting a baby in a month. Their first. I had nothing to say then, but now that I know something about expecting, I wonder if he was worried standing out there with me watching the sky shift for hours. Did he wonder if she was going into labor, if he would be there in time? Would his day end with an infant swaddled in a hospital crib?

Ely was the closest town, a good two hours away, and it was where the tow truck would be coming from. I would discover Ely years later to be a favorite poet’s hometown and I would tell her, to her great shock, I’d spent three days there waiting for my car to get fixed. I hoped the story would impress her, but it just made me seem odd.

I forgot the state trooper’s name because I was wondering how I ended up in Nevada. A college student from a New Jersey suburb, the daughter of immigrants, I could never turn my papers in on time or show up to Friday classes. What was I doing here? I forgot his name because he told me that if I hadn’t had those three crates full of books in the backseat the car might have flipped, flown farther. I was lucky I hadn’t died, he said. Ely, it would turn out, was a way station for busted-up cars and dumbstruck passersby. The town had long made an industry out of accidents like mine.

I might have burned, curled in the front seat, Joni Mitchell moaning, and never stood all day in the desert overwhelmed by being and shame. I forgot so much, but I did not forget myself or that included amongst those books were M. L. Rosenthal’s edition of Yeats’s selected and Jorie Graham’s The Errancy, what I read the nights he went to bed without me.

I can’t remember the songs that kept playing as dusk made our standing there along the road more strange or the state trooper’s name, a kind man who would forever be a stranger to me. I remember I wanted to seem like I wasn’t scared, that I was accustomed to the West and accidents. He pointed out plants other than lupine, and those I cannot remember either.

4.

I remember these words—

Yeats: “man’s life is thought, / And he, despite his terror, cannot cease / Ravening through century after century, / Ravening, raving, and uprooting”

Graham: “That there must have been. // That there might have been.”

I have been trying to understand these experiences for sixteen years now. I’ve written journal entries, an unreadable novel, and a handful of poems describing the accident on Route 6, the evenings I watched the light split across the desert, our silent hike up Mammoth Mountain, the Arby’s sign lighting up my nights in Ely like a full moon, smoking cigarettes outside a diner in Bishop – all of this description blind, in the end tossed out.

And yesterday I came upon these words—

Thoreau: “What we call knowledge is often our positive ignorance; ignorance our negative knowledge.”

5.

If you still read maps, on maps of the western United States you’ll notice that some lakes are drawn with a dashed rather than completed line:

They are lakes you might pass by in the desert and mistake for another sun-scorched field. Not quite dead, nor exactly alive. Owens Lake is one of these, a dry lake that reads in my atlas as a cartographer’s elegy. We drove by it on our way to Lone Pine and I asked him how anyone could still reasonably call it a lake.

What remains is an ecosystem grieving its originary state. Grieving, though, is an overwrought word; for, what remains is not human and does not demand the burden of my imagination. It is a salt flat or a playa, a desert lakebed dried out since the 1920s because its streams, which once flowed salubriously into Owens River, had been diverted into the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Strong winds whip up the lake’s remnant chemical dust, dispersing clouds of alkali all over the West. Children a hundred miles away develop asthma from the recurrence of these relentless dust squalls that pollute the air and have transformed the loss of Owens Lake into a menace for generations of dwellers near and far.

But his answer was simpler than the casual research I conducted a decade later, when I was just beginning to understand the environment as a private history that needed uncovering. We parked our rental and wandered towards the colorless flat. I was struck by all the nothing we were looking at. The heat that kept us from standing too close seemed to seal us into an air-tight jar, so that we were never far from touching yet never entirely free from each other.

“With the lake gone, the air here’s poison,” he finally answered.

I put my hand to my face. He laughed, realizing that I was scared, always scared, of dying, and then I laughed. Together, we imagined an edge to circle, drew closer to what may or may not have been the lakebed. It wasn’t that kind of poison, or at least its hazards were not immediate or immediately fatal. It was the poison of the past – human intervention and the desert’s natural habits of arid erosion – and it was the poison of the present – incontrovertible, sullied.

6.

Dear Cristiana,

You asked me to write about erasure when I am not wholly convinced that anything can be erased.

My favorite erasures speak to erasure’s futility. South African artist William Kentridge’s animated films consist of charcoal drawings on a single sheet of paper that get repeatedly erased and redrawn. They have been described as palimpsests because no image, once drawn, can fully disappear. Charcoal smudges the background of every subsequent drawing. He draws South Africa and redraws it as new South Africa, but the landscape of apartheid persists despite its abolishment. The past pains the present, and cannot be forgotten or unseen. A black man’s weeping face and an overworked, now unworkable field comes to shadow a building or a stranger’s profile. But each image retains the integrity of its first form, however ghostly. In the films, the animation makes these shifts in scene seem swift as thought, suggesting a composition process that is associative, generative, and gravely urgent. What the artist sees is informed by what he has seen before, and so his imagination always walks alongside history.

Erasing what cannot be erased is perhaps where art succumbs to history. Perhaps the futility of erasure bolsters the argument against art’s claims to fashion the impossible. Perhaps there are no new worlds, only the residue of older ones. I imagine Kentridge’s dry charcoaled hands as a palimpsest of his efforts. He cannot redraw the past away and he cannot stop drawing. In the process, nothing gets erased.

My attempts at erasure are hardly as significant or artful. I trash poems on my computer or into the wastebasket under my desk. I leave behind people and homes and call it wandering. Dust collecting in the soles of my shoes might be my palimpsest. I remember upon moving to this Ohio prairie finding a favorite pair of sneakers caked in the ruddy mud of a once-loved mountain trail in Virginia. I wore them as is and they’re now testament to all the walks I’ve taken with my dog in the past three years of living in three different states. Rain makes no difference: it cleanses the soles but also leaves them more worn.

But this, my observation, would seem to exemplify reductive thinking and that is not at all what erasure is about. Erasure enhances Emerson’s claim that “Our age is retrospective.” He was writing in 1836, but our age is so retrospective that we look back as a means to look forward. Erasure as practiced by American poets Ronald Johnson, Jen Bervin, Srikanth Reddy, and others reveal how the past serves as material for new art.

Sixteen years ago, I made two trips to the American West—the first, contentedly coupled; the second, inexplicably solitary—roaming the loneliest highways of California and Nevada. I cannot say I have nothing left from that time, though I often wish I could. There are those books, that Joni Mitchell cd. My car did not survive the accident, despite three days of nobly attempted resuscitation. I left its carcass in a lot behind the auto mechanic’s shop in Ely, a lot he called a graveyard, and then hitched a ride with the mechanic’s ungarrulous friend to Salt Lake City, where I caught a plane to Chicago. I shipped the books ahead of myself and found the boxes outside my apartment coated in desert dust. I waited a week before I called the young man who did not love me to tell him I’d arrived home safely, and then, after, I wept knowing that everything I wanted from him, everything I left behind, lost, would persist in me as pain.

Erasure is an unrequited art. It expresses our desire to forget and, at the same time, the impossibility of forgetting.

In the way of explanation this is the best I can do.

7.

On the White Mountains, east of the Sierra Nevadas, bristlecone pines endure vagrant hands seeking the feel of immortality. The oldest trees measure 4,500 years, their trunks gnarled by millennia. And yet, though they are the oldest living organisms in the world, bristlecone pines have not lived long on the scale of geologic time.

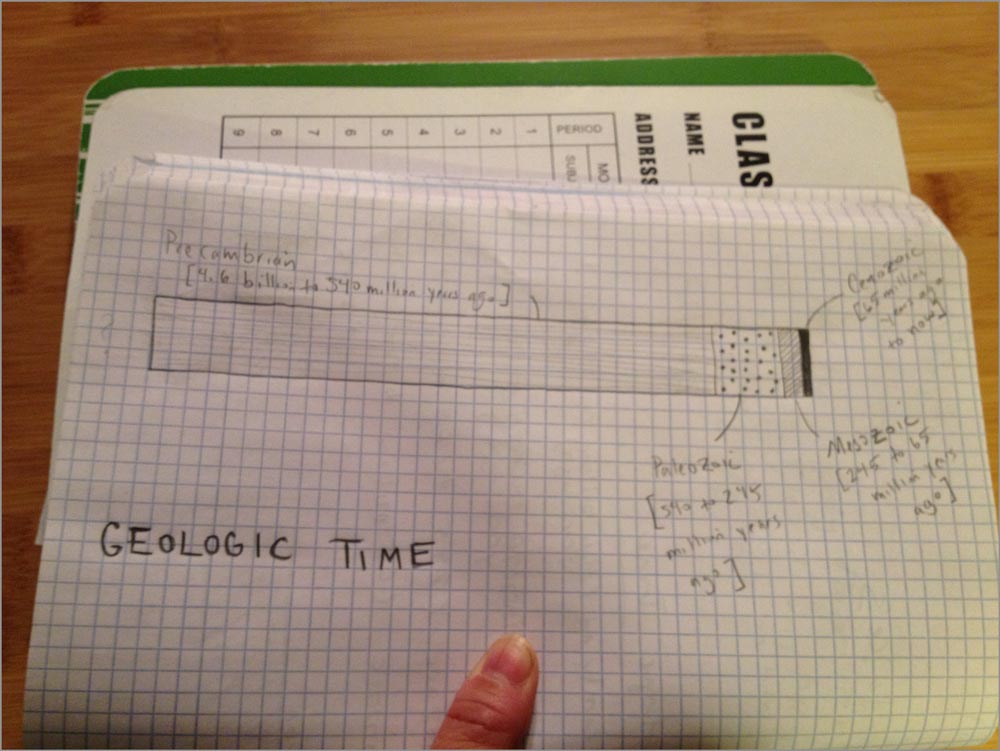

Here I must reveal the extent of my ignorance: I had not known that living, of any kind, has gone on for so long, or that we humans have been so fleetingly realized. We, and I am including the bristlecone pine in the pronoun, live in Cenozoic time, which extends from 65 million years ago until this very moment. Geologic time, though, stems 4.6 billion years ago, beginning with Precambrian time. I found the numbers in a study on California geology and could not fathom what they meant, the measure of finitude and our brevity within that measure, until I drew this in my notebook:

That thin black bar on the far right end is the time we inhabit and it encompasses millions of years. My sixteen years of being preoccupied by the American West and a very old tree would not even comprise a visible increment on this page.

Our being, inconsequential as the daylong existence of a mayfly.

It had taken hours to work our way up to a cold, rocky grove, where the bristlecone pines stood grand and inscrutable as sphinxes. Some were fenced in for preservation, either to protect delicate health or to ward off hikers who, struck by the terror of sublimity, wanted to hurt and vandalize the trees. I saw hatchet marks feebly sliced into bark. One tree bore a stripe of red spray paint. I, too, wanted to feel the trees, to touch what seemed so ancient it became at once mythical and creaturely. I wanted to feel the imprint of every millennia lived and let some primordial dust mark me for eternal life.

How do bristlecone pines die? A question I never thought to ask then and have yet to research.

I discovered recently that Mammoth Mountain, another climb we made, is a volcano. The more accidental knowledge I acquire the more the realm of my ignorance expands. I had not known that standing up there in the sky with the young man who did not love me would eventually become an indelible memory of freedom or that when I think of bristlecone pines or the various mountain trails we ascended I would remember a sharp and clarifying loneliness. We were standing on a volcano, pursuing a dry lake. We were palming the oldest living organisms in the world. Yet, with every new adventure we experienced together, I was learning what it meant to be alone in the world and, consequently, what it meant to be gone. I was affecting my own absence in nature, and as palatial as the scope of feeling grew in my chest at his presence, I had the appalling suspicion that our gestures and words, our hurried reconciliations followed by long nights of silence, were all forgettable.

A better question might be – how do bristlecone pines live? To face what will outlive us is one of nature’s extravagances. I don’t remember how much time I spent gazing at bristlecone pines that day or how many monstrous, arthritic branches I reached up to, but I remember that an intimacy formed between me and the trees. It was not my imagination that we shared a stillness, a tacit biology, however modest, and lost in that pause of time I let myself vanish into my own awe.