Paint the town red: to get hammered or schnookered, fit-shaced or pissed, tore up, off your tits. The origins of the idiom are rowdy as binge. Oscar Wilde claimed Dante’s Inferno: “We are they who painted the world scarlet with sins,” an accusation that exceeds the bender to include an inventory of perversions, beginning with sexual deviance. The OED dates the earliest recorded use of the expression to the late nineteenth century, but Jonathon Green’s three-volume slang dictionary proffers an 1837 riot in Leicestershire, when the Marquis of Waterford—Henry de la Poer Beresford, a.k.a. the Mad Marquis—caroused with some hooligan friends through Melton Mowbray, painting its toll-bar and other buildings red. This might’ve been after a foxhunt, and blood was spilled perchance.

The mayhem is recorded in R. Ackermann’s painting A Spree at Melton Mowbray, Or doing the Thing in a Sporting-like manner, in which three gents wearing scarlet are turning the sign of the White Swan red, while two blokes smear the Post Office window. One brushstrokes the back of a fleeing watchman, as three redcoats sully another guardian’s face. Move to America: Rudyard Kipling referred to Chicago in 1889—“They would do their best,” he wrote in Abaft Funnel, “towards painting that town in purest vermilion”—while the Chicago Advance mentioned New York City on Independence Day 1897, when “The boys painted the town red with firecrackers.” William S. Walsh’s Handybook of Literary Curiosities situated the phrase in the era a Mississippi steamboat captain, riled by a foe, would holler, “Paint her, boys!” as his crew soused the fires with fuel, casting a red glare on the night sky and surrounding scenery. Whatever the source, it’s revealing that carnage and debauchery are figured in terms of a painted metropolis—graffiti’s plat. The varieties of red devised by spray paint manufacturers comprise a paean to bedlam unto itself: Apache, Spitfire, Kerosene, Doom (all sold by Beat); Etna, Tango, Riot, Chianti (Clash); Vegas, Hot Sauce, Red Alert (Plutonium); Tornado, Swet 100 Traffic, Pussy, Signal, Esher Dirty, Mad C Psycho, Amaranth (Molotow); and fun with the sun chez Krylon: Tomate sechée au soleil, Coucher du soleil toscan…

Elizabeth Taylor paints Gotham red, as Gloria Wandrous in BUtterfield 8, the 1960 film adaptation of John O’Hara’s novel. Waking up alone in a strange apartment, she sashays around its duck blue salon, the tint picked up by her mascara, while the creamy appointments, like candlesticks, are reprised by the bed sheet she wraps herself in, later by a silk and lace slip, finally a cashmere coat. Her red and gold evening dress, torn down the middle, is a casualty of last night’s screw. Shoes match the dress, and both match the cushion on a chair. Decanters of red perfume arranged on a table, she pours herself a whiskey or bourbon, brushes her teeth in the highball tumbler. Soon she’ll cab to a male friend’s flat, red brick to go with her candy apple ride. The guy’s girlfriend, who hates her, will refer to Gloria as Little Red Riding Hood. Eventually she’ll shack up at Happy’s motel, its neon sign blinking red, red, like the blood from her lover boy’s messed up mouth, when he calls her a tramp in public and takes a punch. Nor can she argue with the insult: “Face it,” she’ll cry to her mother, “I was the slut of all time!” Wondrous and wanderlust rolled into one, she’s obviously the lady for Weston Liggett, a chemical company lower exec whose “drinking, letching, and lying” are infamous. Sadly, it won’t work out for the pair, neither in the 1935 book nor in the Metro-Goldwyn movie, where even the end will arrive in red titles. Way back at the beginning, though, when she’s putting her makeup on in the mirror and finds $250 Liggett has left her in cash, Gloria squiggles some pissed-off graff on the glass above the mantel: no sale. (This only happens in the movie version.)

The cursed, cursive, abject scrawl of a call girl trying to earn some self-respect—minutes before she steals a mink coat belonging to Liggett’s wife Emily—, the spited lip gloss caveat finds a corollary, two decades later, when little Danny Torrance scratches a warning in lipstick on the bathroom door, in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. When Danny’s mom Wendy reads reᗭЯum reversed in the looking glass, the satanic portent is urgent and clear: murdƎЯ. Mother and son will escape Jack and his hatchet in the labyrinthine snow, but Gloria isn’t so lucky: death by steamboat in O’Hara’s pages, car crash in Hollywood. (The scarlet harlot on whom both versions are based, Starr Faithfull, was found dead on Long Beach in 1931.) One of the women writes on a mirror, the other needs a mirror to read. Both inscriptions are six letters, but the first is defiant, by an escort scorned, the second the backward word of a child possessed. For a mistress, red is the color of the heart, adultery. But the mad know better, and so does the kid: murder literally begins with red.

Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1970 heist film Le Cercle Rouge opens with four men in a car, running a red light in Marseille. Just out of the clink, Corey, played by Alain Delon in a trench coat and dark mustache, caroms a red billiard ball around a table. Meanwhile, in pursuit of a fugitive named Vogel, police chief Mattei takes a helicopter equipped with a rotating red siren on top and a red and blue bullseye decorating its chassis, while various roadblocks, set up across the region, use round red signs. The American style cars have red taillights, the jewelry cases in Place Vendôme are fitted with gumdrop red alarm bulbs, and the dancing girls at Santi’s club wear crimson satin garters, intermittently visible as they lift their rhythmic legs in cabaret. The film’s epigraph states,

Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, drew a circle with a piece of red chalk and said:

When men, even unknowingly, are to meet one day, whatever may befall each, whatever the diverging paths, on the said day, they will inevitably come together in the red circle.

Despite this emphasis on red, the the cinematography is tinted—if not tainted—malachite, doused in a fog of inimical, chemical green: emerald forests with shamrock moss; drab, lablike interiors, from prison cell to police department, milky to the point of pastis, or sick, in urinary citrine; baize wallpaper; aging tweed; the surveillance camera TV reel in spectral celadon. Red, we might say, is a red herring. In fact, the epigraph turns out to be made up, the director’s name no less; he was born Grunbach. Maybe he liked Moby-Dick—quest narrative on a grander scale—or Melville’s novel Pierre, whose protagonist is writing two books: one for public consumption, the other, private, written in blood, never meant to be read. Does Oulipo have a modified lipogram, where the final e of a word is lopped off? Melvill in Bellevill:

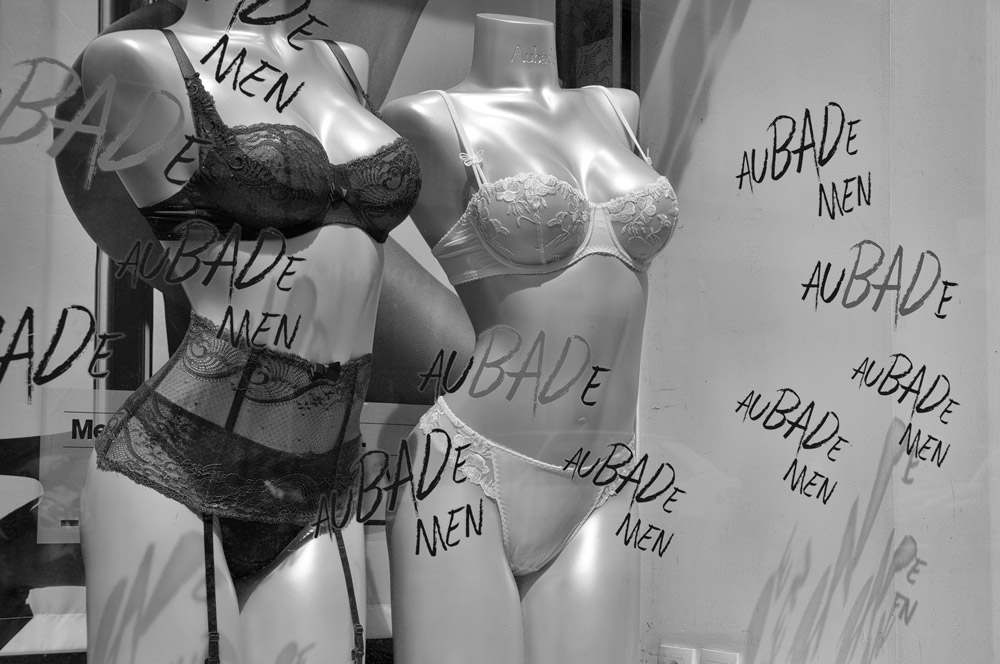

Printed and slapped to this window display, as if dashed in red gloss by a flirt on the fly, these Aubade odes, in a cutie pie way, are as dramatic as the Théâtre du Vieux Colombier ensconced across the street, whose loges are lined in deep, seductive burgundy and gold. Infomercial to the theater’s centennial of serious drama—“contre toutes les lâchetés du théâtre mercantile,” as its founder Jacques Copeau once put it—, this lingerie and lipstick shtick puts content in conversation with form: bad dialoguing with red. Further, the busty polystyrene broads, no less than the message they conspire to massage—word become flesh, flesh become product—, elicit the hit television series Mad Men, from its ad office exclusivity, all art deco curves and skyscraper views, to its nostalgia for cocktails and smoking and suits, low cut blouses, illicit liaisons. O bawd, o bod—a whiff of as-if graff. In the medieval period of the troubadours, an aubade was a love song or song of parting, sung to a sleeping woman at dawn. But our world is upside down.