mole or twin

For a long time, nothing came between the poems on water and the poem on fire.

Neither touching nor at any visible distance, they seemed alibis for each other. It is easy now to see their failures, brilliantly shiny.

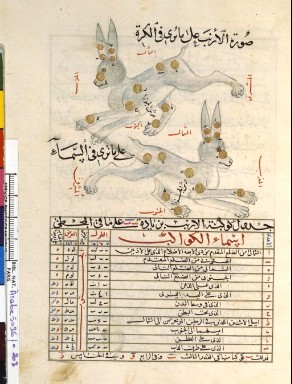

There were poems I thought to write. I returned again and again to The Book of Fixed Stars. The title fascinated me almost as much as the intricate double drawings. One from outside the celestial globe and one from inside. Swans drawn as if affixed to the sky with dissection pins, the horse’s head levitating above a star chart, rabbits leaping over one another.

And then, the beautiful twins, their bodies overlapping so that I can almost see my husband and his brother in the womb, arm touching thigh.

Though I have no solid medical evidence, I believe I once had two conceptuses. The irregular pregnancy, the alarming, oddly shaped placenta, my daughter’s enlarged and reddened breast. Perhaps the mole we thought we saw on several ultrasounds burrowed out somehow during those early months, leaving her inconsolable until the age of two. When I ask Greta about her life in the womb, she reports warmth, and then, suddenly, its absence. Something knot, and then not, on the other side of the membrane. Al Bakar, the White Ox, is visible from Southern Arabia, and I will likely never see it.

But, I’ve left the title behind. We know that stars have a parallax, not to mention motion that is more than apparent. I kept feeling fixed stars and fits and starts. What if stars have origins, parents of sorts, and what if it is a kind of betrayal to give them new names? How are the stars’ magnitudes figured, I wonder. I am sure I can find the answer to this question, but instead I leave it behind as well.

Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi also known as Abd ar-Rahman as-Sufi or Abd al-Rhaman Abu al-Husayn is known in the west as Azophi. I keep imagining a ferryboat carrying Azophi slowly toward me through galaxies he liked to call clouds.

He seems a beauty, and he hides his face behind black paper pierced with holes. Whether this is the veil of life or the veil of death

remains

cleave

“At home” is not a container but a site and an event. The house is too small, and children regularly choose to pee in the backyard as opposed to waiting for someone to get off the pot. Bodily analogies tempt me, and while I have heard individuals say they feel they’ve been given the wrong body, I’ve never heard anyone say they’ve outgrown their body. And yet the house is a kind of body that seems never large enough until, perhaps, it catches up with death, or burns to the ground.

Blanchot says the I never dies, that is, the I doesn’t say I am dead otherwise it would master its own death, and we all know death’s master is death itself. Even when I figure an afterlife, I realize that if it has a master, it is itself itself as well. Given the difficulty we have distinguishing between consciousness put into question and consciousness of being put into question, it is futile to do anything other than tell the right kind of bedtime stories, the kind that enlarge the house and render death an inaccessible phenomena we ought not discuss at this late hour. I realize this may turn out to be an ineffective parenting technique, but I go on in hopes of comforting frightened but sleepy children.

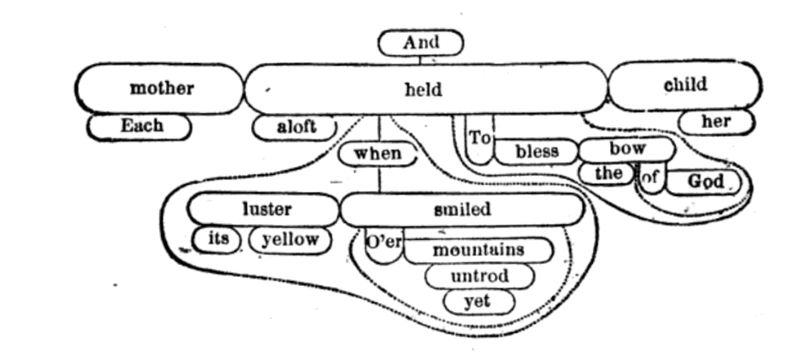

With the children in their bunk beds, I think of writing a poem on sentence diagramming. The diagrams are as beautiful as Azophi’s star charts, but words radiate more comfortably than pinned stars. I have been more than undisciplined lately, drinking in the evenings, sleeping until 7 am, riding my bike instead of reading. In their book, Higher Lessons in English. A work on English Grammar and Composition, In which the Science of the Language is made Tributary to the Art of Expression. A Course of Practical Lessons Carefully Graded, and Adapted to Every Day Use in the School-Room, Brainerd Kellogg and Alonzo Reed insist, “As a means of discipline nothing can compare with a training in the logical analysis of the sentence.” They employ the word “fitness” in a manner entirely new to me—as in, the (eternal) fitness of things to their words, or is it words to their things?

if it flickers

(t)here

hearing a step

in that ‘cleave’ of being which each of his creatures shews to God’s eyes alone

(Hopkins)

then

it remains

the parse tree

The history of the American parse tree begins not with Kellogg and Reed, but with S.W. Clark’s earlier obscene balloons.

Dangling as they do from the penis of the sentence—held—words are stored like semen in two misshapen sacs. As is the case with many penises, small benign growths and protruding veins give this particular sentence balloon its unique shape.

And yet (at its reaches)

mother And child

Each aloft

And(afloat)

sentences on sentences

I manage to write a handful of poems on sentences, but really, they turn out to be illustrations on sentence-making, organized by subject. Here’s one such poem, written in bed:

Sentences on Sadness

I admit I have been terribly sad.

While writing this sentence, I am weeping.

The danger is that the situational, slowly, but always, becomes habitual.

That awkward figure, God, made us coats of skins.

We make our children coats of skins too.

Sensical, borne as she was from nonsensical, floats above and beyond her mother.

What is left is like a mist hovering, threatening not to disappear, and threatening in

its disappearance.

I am worried about worry, what it does to the body, to the psyche.

How it has its way with me while I sleep, while I winnow down the list, while I wipe

more asses than I own.

I was told that there are activities better done for twenty minutes every day than

for hours once a week.

In this way, perhaps writing and exercising are akin to crying.

As far as sentences go, I fear mine are unventursome. Eventually, the titles of the sentence poems I mean to write far outnumber those actually written.

Sentences on Contraception

Sentences on Lenten Waiting

Sentence on War

Sentences on Dreams about Nightmares

Sentences on Nightmares about Dreams

Sentences on Stealing

Sentences on Preschool

Sentences on It

Sentences on Shitting

Sentences on Seaboards

Sentences on Shapes

Sentences on Falling (off a chair, swing, hammock or bed)

Sentences on So-and-So

Sentences on Cereal

Sentences on If-Then Configurations

Sentences on Illegitimate Rape

Sentences on Husbands

& of course

Sentences on Sentences

hirmos

Several centuries ago, sentence meant question and period meant sentence. Period, a transliteration of the Greek word periodos (“a way around”), was a collection of words related grammatically and semantically. Just as words within the sentence disappear into a larger notion, period singularizing itself via Medieval Latin, could only hold by holding together. In 1597, Calligrapher Peter Bales calls the character which signifies but sounds not

“a full pricke.”

that which pierces the page also menstruates

In John Gent Smith’s The mysterie of rhetorique unveil’d wherein above 130 of the tropes and figures are severally derived from the Greek into English : together with lively definitions and variety of Latin, English, scriptural, examples, pertinent to each of them apart. Conducing very much to the right understanding of the sense of the letter of the scripture, (the want whereof occasions many dangerous errors this day). Eminently delightful and profitable for young scholars, and others of all sorts, enabling them to discern and imitate the elegancy in any author they read, &c., the word hirmos, a bond or knot, is offered as the period’s twin:

a figure whereby a sudden entrance is made into a confused heap of matter

knit or coupled together

prick, like a pink balloon

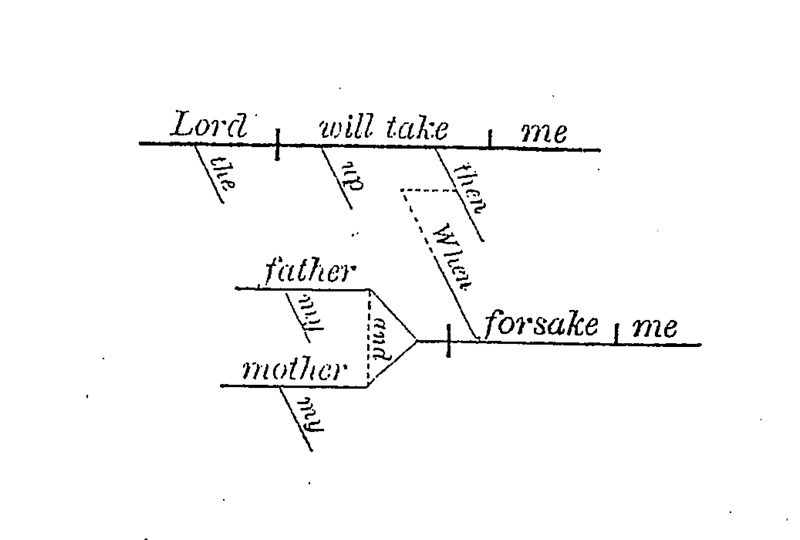

With their broken lines for coordinating conjunctions, their small x for what is not said but implied, their angled lines for participles, their hovering lines for direct address or interjections, and their tails for articles, it isn’t hard to see why Kellogg and Reid’s sentence diagrams take hold while Clark’s balloons float away in the distance until we see, first, a prick of sky, then a trick of the eye. Beyond their reassuring symmetry, they offer a hierarchy meant to bridge belief and proper dependency.

I come to this parse tree in a “specimen copy” once held by the Library of the State Agricult’l College, Fort Collins, Colorado. As far as I can tell, I am the first patron since September 1996 to withdraw the book from Colorado State University’s Storage Overflow Building. My library liaison has advised me to check out books that I would like the library to keep else their future, should they be granted one, will be digitized. In Lesson 59, Complex Sentence-Adjective Clauses, I find the following sentence eagerly awaiting diagramming:

The lever which moves the world of mind is the printing-press.

Ah

the word

x the lever to which you referred

several sentences

I am aware that refinement of mind and clearness of thinking usually result from grammatical studies. (Lesson 128)

&

The guilt of the slave trade, which sprang out of the traffic with Guinea, rests with John Hawkins (Lesson 59).

&

What means that hand upon the breast of thine? (Lesson 120)

Perhaps it is because I am attracted to sentences like these, all lifted from Kellogg and Reid, that I can’t seem to interest myself to the same degree in today’s trees, which, can be parsed into a seemingly endless array of structures, some more closely resembling a razed forest than a growing tree.

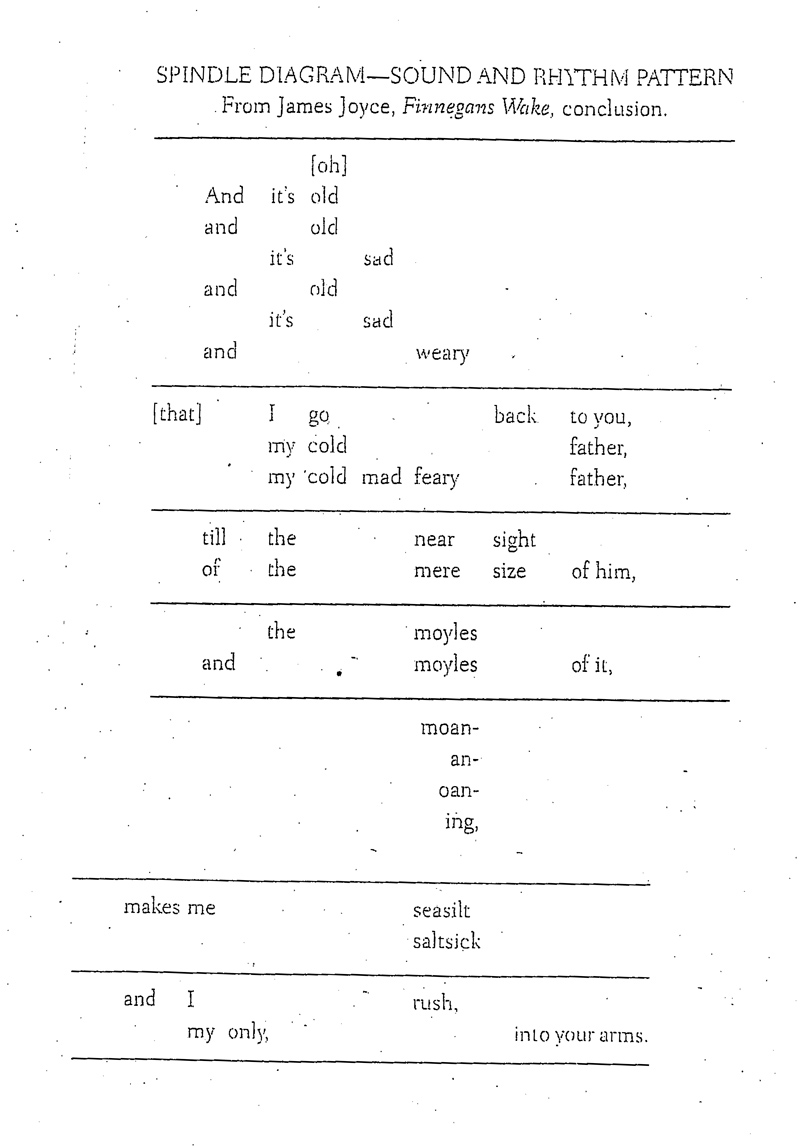

William Gass’s Spindle Diagrams, which chart sound and rhythm as opposed to syntactical movement, seem to be sending out shoots of some sort, but they are more like the understory of a forest than erect trees.

grammar grammar

After expatriating herself, Gertrude Stein stayed away for over thirty years. When she did return, it was to deliver several lectures, one of which, “Poetry and Grammar,” fondly recalls her childhood of sentence diagramming. “When you are at school and learn grammar grammar is very exciting. I really do not know that anything has ever been more exciting than diagramming sentences. I suppose other things may be more exciting to others when they are at school but to me undoubtedly when I was at school the really completely exciting thing was diagramming sentences and that has been to me ever since the one thing that has been completely exciting and completely completing. I like the feeling the everlasting feeling of sentences as they diagram themselves.”

Thanks to today’s many computer-generated parsing programs, sentences really seem to diagram themselves, but the joy is lost. It is true that the most straight-forward of these new trees, which are reminiscent of a Calder mobile, manage to relate some of the principles of balance often found in the “successful” sentence. But the sentences lack character. Despite the fact that I have searched Treebank after Treebank, Parsed Corpus after Parsed Corpus, the wood is never green, the body no longer living.

These new trees break down along the lines of either constituency or dependency, though

one can create a hybrid tree. Glancing at such trees, we see,

visually,

that hierarchy has replaced multidirectionality.

Nonetheless, I find I cannot leave off without including the results of at least one of the many on-line diagramming applications I performed. Having submitted the original sentence—“I feel so Americanly close to Jones Very, so tenderly tied to the tragedy of marriage (incest?) and madness”—to Version 4.0: A Phrase-Parser. I was given the following gifts, a chart of linkages and a constituent tree:

+-------- MX*p-------+----------

+---------- Pa----------+ +---- Js---+ +------- Xd-------+ +---- J

+- Sp*i+ +------- EAxk------+- MVp-+ +-- G--+ | +- EExk+--- Em--+- MVp+ +--

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

I.p feel.v so [Americanly] close.a to Jones Very , so tenderly tied.v to the

-------------------- Xc------------------------------+

p---+ +------- Jp-------+ |

| | | | |

tragedy.n of marriage.n incest.n and madness.n RIGHT-WALL

+-------- MX*p-------+----------

+---------- Pa----------+ +---- Js---+ +------- Xd-------+ +---- J

+- Sp*i+ +------- EAxk------+- MVp-+ +-- G--+ | +- EExk+--- Em--+- MVp+ +--

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

I.p feel.v so

[Americanly] close.a to Jones Very , so tenderly tied.v to the

-------------------- Xc------------------------------+

p---+ |

D*u-+-- Mp--+-------------- Jp-------------+ |

| | | |

tragedy.n of marriage.n incest.n and madness.n RIGHT-WALL

Constituent tree:

(S (NP I)

(VP feel

(ADJP (ADVP so)

Americanly close

(PP to

(NP Jones Very

(VP ,

(ADVP so tenderly)

tied

(PP to

(NP (NP the tragedy)

(PP of

(NP (NP marriage incest)

and

(NP madness)))))))))))

every very

I discovered the poet Jones Very accidentally, though I don’t recall where or how. I do know it was his name that struck a cord, so excessively of itself. A child of first cousins, his given name was his father’s, his surname his parents’. Consanguine marriage wasn’t illegal in the United States until after the Civil War, and Very, living as he was on either side of the split that joined us, was not technically the offspring of incest. I recently read that some 80 percent of marriages across history have been between second cousins or closer. And aren’t our first sexual experiences so often with our cousins? The only people who would call those exploratory-bunk-bed-romps incest are adolescent counselors desperate to offer explanations to concerned parents and even more desperate to find some need for extended, overpriced therapy. The closest Old English comes to the word “incest” is “sibliger,” which simply means “kin-lying.”

And yet Very respected no figure more than Hamlet, who was, he said, the noblest of Shakespeare’s characters, the only one left to consider questions of being. “With us, to be rich or not to be rich, to be wise or not to be wise, to be honored or not to be honored,— those are the questions.”

As if an auxiliary verb

must always serve

some other word.

No other character, Very says, better reflects Shakespeare’s own character. Hamlet’s mother married “with such dexterity to incestuous sheets!” Not because she married her own blood, but because she was lying with, to, and about kin.

Brothers Isaac Very and Samuel Very, Jones’s grandfathers, were seaman, as was his own father, the first Jones Very. But the younger Jones, having sailed with his father for over a year, returned to land with no interest in setting sail again. Despite their shared blood and maritime occupations, there was a curious chasm between the Very families. When the elder Jones Very died, leaving behind his wife-cousin, Lydia Very, and their four children, his father, Isaac Very, tried to claim what little money the younger Jones had left. Isaac Very accused his niece-cum-daughter-in-law of concealing, embezzling or conveying away some Twelve-hundred and fifty dollars, an unspecified amount of gold, and the deceased’s quadrant, sextant and spyglass. Lydia Very insisted she never found the money, and intimated that she believed the gold was stolen by her own aunt-mother-in-law. As for the celestial navigation instruments, Lydia Very told a court of law, “I was his wife and these were his children, and I thought we had the best right to them.”

In-law

the court agreed.

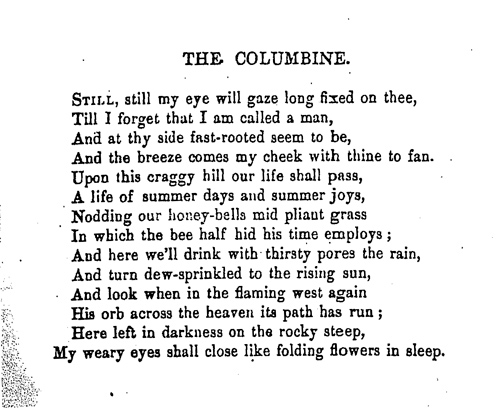

columbine

No Melville, the sea hardly ever serves a subject for Very, and when it does but once or twice, as in “The Sight of the Ocean,” Very’s lines are as weary as his ocean wave:

The plaintive wave, as it broke on the shore,

Seemed sighing for rest forevermore.

But in Very’s eyes, the waves of Walden Pond did not tire of their lonesome activity; rather, they were in chorus and crescendo with one another. Very once asked Emerson to look out over the pond and “see how each wave rises from the midst with an original force, at the same time that it partakes the general movement.’”

Very seems himself to be describing himself, a wave in the Transcendental sea, one that rose originary, but lent and borrowed its force freely. During his first visit with the Transcendental Club in May 1838, Very apparently spoke so eloquently that Bronson Alcott declared, “as if, in answer to the inquiry whether Mysticism was an element of Christianity, here was an illustration of it in living person, himself present at the club.”

Elizabeth Peabody and Nathaniel Hawthorne, Very’s Salem neighbors, both admitted his genius, the latter writing, in 1842, “Jones Very, a poet whose voice is scarcely heard among us by reason of its depth, there was a Wind Flower and a Columbine.” Very had almost 40 more years of life ahead of him, and yet “there [he] was.” Is such playfulness with tense prophecy? I own every columbine I can hold. When I bought my first Colorado home, I pulled what I thought was a weed, and now I see its resilient seed, first to bloom through the fire. The flower has two names too. Not just columbine, which means dove, its bloom resembling five doves huddled together from above, but also Aquilegia, Latin for eagle, the petals its claw.

If you want the flower, and not the school shooting, you must indicate as much in your search.

A voice scarcely heard.

& the poem harder to find still.

Perhaps Hawthorne renames Very the very names of his poems because, in them, he forgets his own name. He doesn’t forget he is a man; he forgets he is called one, and such forgetting is the beginning of assuming another name. Still, still he seems to be born in this poem, and he surely dies here, in the flaming west. But slowly, with one extra foot in the final line, so that flowers may be folding.

or not to be

But it was Emerson who devoted the most attention to his “brave saint.” As many times as I have read Emerson’s “Friendship,” I never knew Very was the man who made every other man see society’s “face and eye” rather than its “side and back.” It was Very who prompted Emerson to ask, “To stand in true relations with men in a false age is worth a fit of insanity, is it not?”

Very’s fit of insanity took the form of prophecy. As a professor of Greek at Harvard, Very had an unwitting audience for his devout sentiments. For eighteen months, he cultivated complete will-lessness, the results of which were rapid weight loss and over three-hundred ecstatic poems taken directly from the mouth of God. But, it wasn’t until he stood before his students and urged them to “flee to the mountains, for the end of all things is at hand,” that he was dismissed from Harvard and admitted into the McLean Asylum for the Insane.

When the diagnosed seems not too concerned with the diagnoses, is it evidence of madness or sanity? While in the Asylum, Very finished his essay on Hamlet, in which he compared the Prince of Denmark to the apostle Paul: “Like the vision-struck Paul, in the presence of Felix, he spoke what to those around him, whose eyes had not been opened on that light brighter than the sun, seemed madness; but which was, in fact, the words of truth and soberness.”

“divinest sense,” says Dickinson

“such a mind cannot be lost,” says Emerson

that shape I am

Perhaps you’ve heard of the McLean Asylum before. Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton,

Robert Lowell, siblings James, Kate, and Livingston Taylor, Ray Charles, Steven Tyler, David Foster Wallace, Zelda Fitzgerald, and a dozen other famous writers, musicians, scientists, and mathematicians took their rest-cures in this extravagant hospital for the rich.

Fredrick Law Olmstead contributed to the design of the facilities, and then he was treated there. It is impossible to say for sure, but it appears as though William James spent time at the asylum as well. In his Varieties of Religious Experience, James offers an example of what he calls “panic fear,” attributing it to a French patient who spent time in an unnamed asylum. According to James’s translation of the patient’s account (“I translate freely,” James writes), one evening having entered a dark room, the patient experienced a great fear of his existence while simultaneously recalling the image of an epileptic man he had seen during his stay in the asylum. The patient reports: “This image and my fear entered into a species of combination with each other. That shape I am, I felt, potentially.”

And, as it turns out, that shape he was. When translating The Varieties of Religious Experience into French, the translator, Frank Abauzit, wrote to James in hopes of securing this account in its original French. James replied, “the document is my own case….so you may translate freely.”

By species, does James simply mean a kind of combination, or does he mean vision? It is hard not to bring to bear so many other things here,

such as, species means:

appearance,

reflection,

a thing seen,

a common quality,

human and all other living things,

distinct

But it also means, to Socrates at least, idea. It is no cogito but it is existence. The word meaning meaning.

When God says, “I am that I am,” maybe he simply means, “I am that I am.” God being cheeky, showing Moses just how slippery language can be, particularly words that point at pointing, like this and like that, I am that iamb

this that

he riddles our riddle back to us

second story

“What I like most about God,” my daughter tells me, “is his stories;” after a pause the pierce of a semicolon, she demands, “And now you tell me one.” One of the most exhausting things about parenting is meeting children’s endless demands on your imagination. A friend, at her wits-end, calls me and admits, “if I have to talk behind another stuffed animal for even one minute longer, I don’t know what I’ll do.” I suggest she cut the head off her daughter’s stuffed bunny, holding its body up to hers, all the while continuing to narrate so that the transformation of mommy into bunny might itself be a kind of cure.

My children clamor after story.

hours and hours of telling stories while driving (to & from school), doing dishes, cooking, serving (breakfast, lunch, dinner & snack), shopping, bathing, brushing (teeth & hair), dressing (children, babydolls & stuffed animals), fastening, unfastening (seatbelts & buttons), wiping (noses, faces, hands & asses), drawing, taping, folding (paper & clothing), packing (lunchboxes, diaper bags & backpacks), spelling, naming, fixing, walking (for pleasure & in a hurry), tying, zipping, velcroing (coats, jeans & shoes), cutting (paper & hair), administering (lotion, medicine & discipline) all the while

I attempt to avoid formulas, but children define stories by their constituents, so that each story must include a baby, an injured pet, and a near-fatal accident. I challenge myself to carry on in ways that are themselves childlike—continue until a red car passes, or the mailman crosses the street, or a child has to pee. After awhile, everything I say is stolen from the bedtime stories I was told, or rather, read. Mothers as backhoes, rabbits among the brambles, run-away children, tired of living in houses, chased home, finally, by the elements.

Eventually, I offer simply an article and a noun, insisting we tell stories in rounds.

Their verb: poops.

Or, I suggest, you tell me a story instead.

I cannot, the youngest says, I’m allowing my brain to rest.

And yet we all invent devices for filling up the crevices and disguising the fissures.

Something Homer once said proves itself true again and again. That is, wine tempts one to blurt out stories better never told. In other words, rather than thinking ahead, it seems I am forever comforting them so that they might stay in their beds.

Every night for 30 nights, I have a strange and moving dream. Our house kindly builds upon itself a second story, spacious and open, into which only I can climb.

30

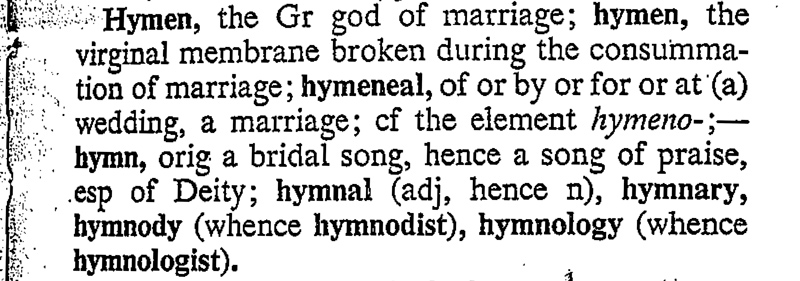

I never planned to follow the poems on water with a poem on fire. The water poems were meant to be erotic, an everyday investigation of intimacy. It occurred to me, after teaching Whitman’s bathing scene, that poetry might know the watering hole where cogito and coitus meet, the one that warmly aches, or gently vibrates, like the hymen, or, more accurately, the spot where the hymen was previously. I’ve come to associate this cavity with the number thirty, the ruptured tissue a three, the whole hole a zero, a 0, or perhaps an O.

If you perform an online search for the word “hymen,” you’ll learn that this vaginal membrane is “a source of confusion, even ‘myth’ for a lot of people.” Myth, indeed. For virgins and their first lovers, this is a place of mystery to which we cling

until, like Catullus, we sing:

Hymenaeus Hymen, come! O Hymen Hymenaeus!

Hymenaeus Hymen, come! O Hymen Hymenaeus!

& he does, tall, says Sappho,

whence womb-fury

‘Tis Hymen peoples every town

he tells Phebe

& now a hymn she sings me.

I wanted to be the number thirty, the thirtieth bather, the age when Jesus started his ministry, the number of silver pieces Judas received. But it was the beginning of Lent, and I had given up sex. I suppose I had hoped, as Dante had, to transform my carnal love into a new life devoted, as the case might be, to Christianity. When Dante’s “tongue of love” speaks,

“the sight of her is humbling to all things”

By day thirty, I was as if blind. I sat at God’s feet, but coitus interuptus as it so often does.

on teaching

By the way, the blow-job scene in Song of Myself is fun to teach. After one class, I received a handwritten, twice folded note from a student that read, “you seem to agree with every student but me.” This surprises me because though I often experience great satisfaction while teaching, or rather, after teaching, I never think of it as the satisfaction of agreement. In the classroom, I rarely feel that I agree with anyone but me, and yet they let me teach. By “they” I don’t mean the administration, or even the students, though I am often shocked when an hour passes and no one gets up to leave. Sometimes, in the classroom, I imagine the ground below me crawling, teeming even, with its own authority. They is the earth that let’s me

but I promised not

to write on yet

another element

though, as Keats once said,

the poetry of earth is never dead

and this poem is for itself itself its own death.

verily

It is a watershed. That is, what the earth does with its elements. The mountains on fire, waters ashore up and down the seaboard, higher and higher. I suppose someone once said the word fire-souled, and from it pliant sandals of fire-cured skin, wood being what allows us to speak without speaking aloud.

The will will will itself away.

In 1838, Jones Very visited Elizabeth Peabody. Looking much flushed, he laid his hands on her head and said, “ I come to baptize you with the Holy Ghost and with Fire.” He claimed his poems were fire-baptized as well, but Emerson saw flaws and asked,

“cannot the spirit parse & spell?”

Emerson thought Very “profoundly sane.”

From my tree, I see three fire-spouts broke out. I want all wildlife inside me.

Wildfire, o oath

I have broken.

Horkos

An oath is an incident that is more than incidental but less than fundamental, the difference between the promise and what is promised. Agamben says an oath binds word and action, making it both curse and blessing, blessing if the word is full, curse if the word is empty. The gods’ first oath is water, the river Styx, life on one side, and on the other, the other. Even when God says, “by myself have I sworn,” he means by the water.

& the blessing be the seed multiplied

as

the sand by the sea shore

the stars in the sky

the blessing be the offspring aplenty, the offspring too many.

There are some things that illustrate others without being anything at all. I’ve watched and watched those lessen in number. Blindsided, the sound of pigeons above the sea seems to make a shape like longing. In plain sight, daylight. People often say, watch and learn or some version thereof. I try to say, upon occasion, something quite opposite. Upon, occasion.

I try also to see what happens when the nested prepositional phrase learns it can, with the help of even the most dismal wind, fly. To move it beyond simply an accessory. But being weary, it finally occurs to me to release it instead, to unleash it on some untrodden patch, some tangle, some mess of bluegrass, some stockpile of trees. Trees which know better our needs. Horkos, depending on who you ask, means also “sacred substance.”

“cursed is everyone that hangeth on a tree”

Having sown, I sit and watch the common oat grow

reverberant, riverbent.