Ghost: I would hold a mirror up

to see my heart – and question my part

among these ghosts of hearts

– Robin Blaser, The Last Supper (libretto)

Robin Blaser at home, 2008, from the Vancouver Sun

“The Hippest Guy in the Room: Poet Robin Blaser at 83.”

So, I’ve told this ghost story a few times over the past ten years but I don’t think I’ve written it down. With the help of a few preliminary parentheses anyone can skip if they like, I’ll try and tell the story here as best as I can. It takes a bit of backing up, as preamble. The events of this story indeed took place pretty much exactly a decade ago. We’d determined to celebrate The Poetry Center’s 50th Anniversary precisely on Saturday February 21, 2004, a date arrived at by noting the first known reading hosted by Ruth Witt-Diamant’s fledgling Poetry Center at San Francisco State College in its then new, and still present location at 19th Avenue and Holloway. [Parenthesis 1 *]

Robert Duncan reading for The Poetry Center,

San Francisco State College, 1954.

KQED-TV first aired April 5, 1954.

Theodore Roethke, according to the documented and archived record, first read from his poems at a live, staged event for the Poetry Center on February 21, 1954. The recording that exists, made four days later, yet earmarking that occasion as initial, was quite obviously made in the absence of his audience, most likely for radio broadcast on KPFA. Maybe Roethke was nervous and didn’t want to be taped reading “live”; maybe an on-site recording wasn’t practical; likely the equipment wasn’t easily available. His was the only Poetry Center reading we’re aware of in that first year of operations to have been taped (other readings that took place in 1954, with Jack Spicer, Robert Duncan, Tom Parkinson, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Madeline Gleason, among them, went unrecorded). A reel-to-reel recording machine, evidently, was acquired before terribly long and the recordings pick up in 1955 and continue pretty much unabated to the present. Regarding the likelihood of KPFA being involved, there was a good amount of back-and-forth between the first listener-supported FM radio station in the U.S., Berkeley’s KPFA-FM, the primary link in what became the modest Pacifica Network – after its anarcho-pacifist war-resister founders (see, e.g., Jeff Land, Active Radio: Pacifica’s Brash Experiment, U. Minnesota, 1999 for that story; Lisa Hollenbach, by the way, who visited the Poetry Center Archives from UW-Madison this past winter, is doing research and writing precisely into the overlap between radio and poetry in those early days). We knew that Ruth Witt-Diamant, as a Professor of English at SF State, had cultivated friendships with Dylan Thomas and W.H. Auden, among others who figure in the creation myth, and that Auden had read his poetry to initiate the new campus in 1953. [Parenthesis 2 **] Roethke’s reading, though, was and is the first audio-documented reading we have that was conducted under the aegis of the brand new Poetry Center, so that February date became an appropriate start-date for the purposes of an anniversary. [Parenthesis 3 ***]

So, it’s February 21, 2004, the 50th Anniversary Reading, fifty years to the day following that inaugural reading by Roethke, and we’d decided to put together an “all-star” event to celebrate. Five featured guest poets, each with their own particular story in relation to Bay Area literary history and to The Poetry Center, with enough poetic ju-ju between them to lift the house. Each of our featured poets for the night would be introduced by another writer with ties to them and their work, as well as to The Poetry Center – and (the triple whammy) these readings would each open with a brief and individually significant recording out of our Archives, which at the time would none of them have been in anything like common circulation. We’d stage the event in Knuth Hall, 300-seat music recital theatre on campus in the center of the Creative Arts Building. If you paid extra for your ticket you got to have “dinner with the poets” in one of the larger music rehearsal spaces across the hall, and through the more than able work of Elise Ficarra and a small gang of volunteers we pulled together a respectable, and donated, modest repast. There was milling. There were edibles, and drinks. Stephen Witt-Diamant, son of Ruth, set up an exhibit in the improvised dining room of photos and documents from the early days of the Poetry Center. There was a palpable buzz in the air of the night.

Our five appointed poets for the 50th Anniversary Reading: Etel Adnan, Michael McClure, Ishmael Reed, Adrienne Rich, and Robin Blaser. As the date neared, Etel had to bow out, unable to get there from where she was living (and lives today) in Paris, France. Barbara Guest kindly stepped in, as her friend and peer. I believe that the sequencing for the evening – with introductions, featured poets, and archival recordings – was set up like this:

• Aaron Shurin intro for Michael McClure / Robert Duncan, 1959 / MM reads

• Kathleen Fraser intro for Barbara Guest / Frank O’Hara, 1965 / BG reads

• Alejandro Murguia intro for Ishmael Reed / Langston Hughes, 1957 / IR reads

• Frances Phillips intro for Adrienne Rich / Muriel Rukeyser, 1956 / AR reads

• Robert Glück intro for Robin Blaser / Jack Spicer, 1965 / RB reads

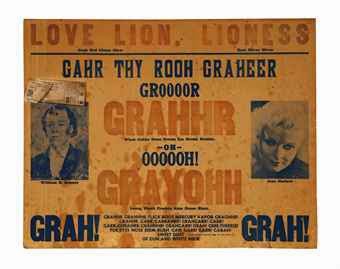

Michael McClure, poster (“Love Lion, Lioness,” c. 1967) with images of William Bonney (a.k.a. Billy The Kid) and Jean Harlow, characters in his play The Beard, is listed for sale at Christie’s.

Barbara Guest in NYC, 1959, photo: Fred McDarrah

There were some extraordinary rhymes to the arrangement, some intentional, e.g. Michael McClure had studied with Robert Duncan – then assistant director of The Poetry Center – at SF State in the mid/late 1950s after he moved to San Francisco from Kansas to study painting under Clyfford Still, who it turns out had left the California School of Fine Arts by the time he got there; and Aaron Shurin had studied with Duncan in the 1980s at New College, where he was the first student granted a Masters Degree from that remarkable Poetics Program. Barbara Guest’s recollection of “dear Frank” was spontaneous, warm, and affecting – the recording coming from the 1965 outtakes of Richard O. Moore’s “Poetry: USA” series, which, done in the year before O’Hara’s accidental death at age 40 on the beach at Fire Island, would prove to be among the only moving-image material that exists of Frank O’Hara. [Parenthesis 4 ****]

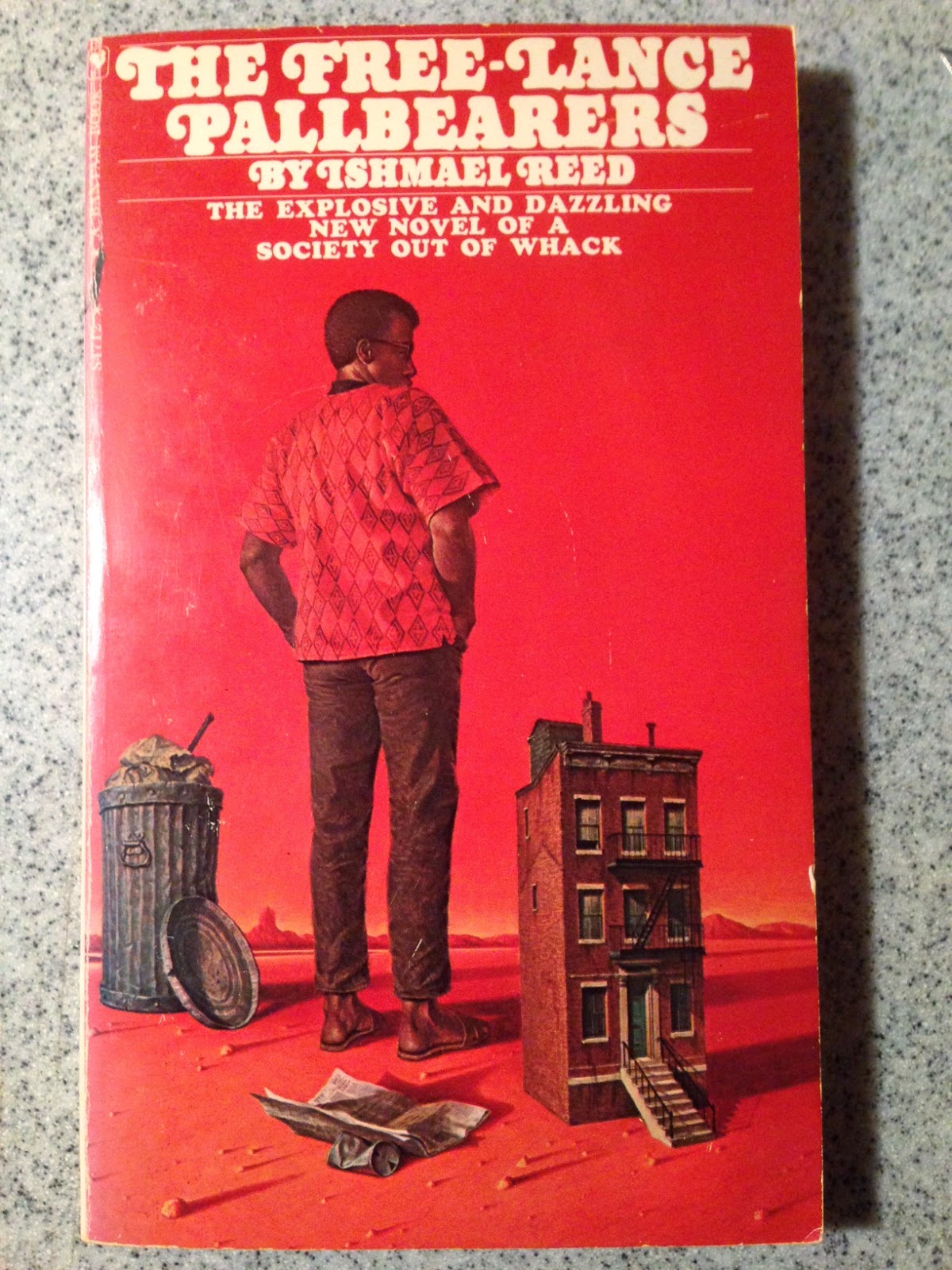

“The explosive and dazzling new novel of a society out of whack” Bantam edition 1969 (Dutton, 1967)

And others came by surprise: Langston Hughes, Ishmael Reed revealed on taking the stage, had been the main man behind Reed’s first novel, The Freelance Pallbearers, being published. Ishmael also did announce, “I’m your representative from Black America” (and he could be right to call it out, anniversary or whatever). Adrienne Rich, we weren’t aware of before she said so, was presently in the act of editing a volume of Muriel Rukeyser’s Selected Poems for the Library of America. One fact that stands out today, ten years later, is that of the five poets reading that night three are no longer with us: Barbara Guest died in the East Bay in February 2006; Robin Blaser in Vancouver, May 2009; and Adrienne Rich in Santa Cruz, March 2012. They were all very much present, and delivering the goods, that evening in February 2004.

And there’s a ghost story. Robin Blaser was closing the evening out, following Adrienne Rich’s powerful reading – the gracious rapport between the two of them, and new recognition of one another being in conversation, was evident. We had earlier invited Blaser to San Francisco to read for his 75th birthday just a few years before, during the first season I programmed for The Poetry Center, in the Spring of 2000. Quite a mass of people had been present before that in 1995 for “The Recovery of the Public World” conference at the Emily Carr College of Art in Vancouver, the occasion devoted to Blaser and his work to mark his 70th birthday and the publication, by Coach House Press, of the first edition of his collected poems, The Holy Forest, this convening of poets and scholars named after that phrase from Hannah Arendt, who Blaser had studied with – he’d been her teaching assistant – at UC Berkeley in the early ’50s. Robin’s last prior appearance reading his work in San Francisco before this, did it go back as far as Bob Glück’s tenure as Poetry Center Director, when Blaser read and then was interviewed by Michael Palmer at the Arts Commission Gallery in downtown San Francisco?

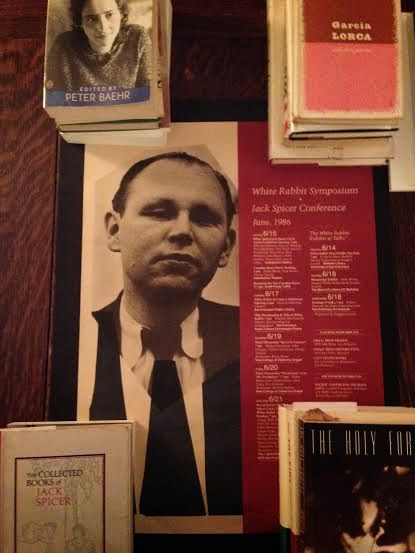

White Rabbit Symposium / Jack Spicer Conference, San Francisco, June 1986, poster by Graham MacIntosh, White Rabbit Press.

I remember an enormous bronze-ish sculpture of a sun – Apollonian – radiating out behind the poet on stage. In back of that would have been the White Rabbit Symposium/Jack Spicer Conference of June 1986, a vast collaborative production held at New College of California, at Intersection for the Arts, Small Press Traffic, the SF Public Library, the Bancroft and USF Libraries, etc. Graham MacIntosh, who is White Rabbit Press, printed the spectacular poster (my copy just came out of the closet and its mailing tube) with Duncan’s White Rabbit pressmark line-drawing traced neatly, and surreptiously, onto Spicer’s necktie.

For The Poetry Center’s 50th Anniversary reading Bob Glück had to cancel, sadly sick at home, and couldn’t provide the introduction for Robin, and I stepped in. We watched a VHS tape of this February 21, 2004 reading a few weeks ago, the first night of our present seminar focused on Duncan, Spicer, and Blaser at SF State in the Poetry Center reading room. It doesn’t exist yet in digital form so I can’t show it to you here. We’re sitting on forty years of video recordings, and the earliest of these, from 1973, is going to make its way to Poetry Center Digital Archive by this summer (as Hamlet’s father’s ghost said, “swear…swear”). For now you’ll have to take the story on faith.

W. H. Auden at Ruth Witt-Diamant’s house, San Francisco, October, 1954 (?)

It was a calm winter night, completely still outside. Not particularly cold, as late February can be in San Francisco, and was for the most part this year. Robin Blaser opened with a charming story, viz his early relations with The Poetry Center: Ruth Witt-Diamant was throwing a house party for W.H. Auden and she asked Robin to round up a car-load of beautiful young men, “which of course I did.... Auden was very appreciative.” Blaser then read from The Holy Forest – after which, he read a good stretch of new work that hadn’t yet been published, a string of short lyrics. Brief, often light-hearted stuff, with a shadow of distance maybe behind it (“somewhat at a distance, as I’ve always loved the other” Blaser writes in a poem, that Kevin Killian had printed as a broadside for an earlier San Francisco visit sponsored by Small Press Traffic). As presented that night, apparently all brand new work, these short, late poems, and written for this occasion.

In the later University of California Press edition of The Holy Forest (significantly “revised and expanded,” edited by his friend, Canadian poet-scholar Miriam Nichols) this sense of the provenance of these last poems is borne out: eight of the eleven poems in that book’s final section (the section titled “Oh!,” cf. RB’s lifelong attraction to what he liked to call “astonishments”) are dated between January 24 and February 17, 2004 – the other three all dated less precisely, just “2004”. He concluded the reading, and the night, with the little poem “a song” read twice – “I liked that so much, I think I’ll read it again” – which he sang. It’s dated 2003, and is placed in the later Holy Forest at the end of a group of similarly brief poems each from 2003, the section titled “So” – appearing right before “Oh!”

a song

there’s a bluebird

in your eye,

a rainbow lines

your many lives

of Eroses.

I dedicate to you

all precious stuff,

all care-full lusts

that burn our lives,

I murmur,

‘luck’

2003

Knuth Hall, Room 132, Creative Arts Bldg, SFSU

Something happened though, just before we were murmured ‘luck’ and had “all precious stuff, / all care-full lusts / that burn our lives” dedicated to us by Robin singing his bluebird song, two times – for luck? The poem just preceding he introduced as “divination by pebbles,” describing the form of soothsaying where you drop pebbles, onto the ground or another surface, and read the patterns that occur by chance. (It’s called psephomancy – the Greek psephos ψῆφος, ‘pebble’, which was used by the ancients as ballots – and so psephology as the study of elections.) What I remember is this: Robin on stage at the podium, a microphone on a bad stand that everybody felt it necessary to adjust its gooseneck when they got behind it, and couldn’t to their satisfaction. Behind him, distant at the back of the large open proscenium stage, thick red velvet curtains. Two videocameras posted to either side, one with the Poetry Center’s long-time videographer and Archives Manager Jiri Veskrna, in the foreground to the right (stage left) according to the camera angle in the video; at the other side, the ubiquitous Kush, Stephen Kushman, fugitive video-maniac who always will turn up at such occasions (stage right). Dueling video cameras, each shooting just outside the other’s frame, and three-hundred seats filled with people listening and watching, with two aisles at either side, rows of seats on each side of the aisles, the aisles leading from twin entrance doors down a banked floor to the stage. Institutional double-doors, the kind with those tubular metal release bars at hip height.

Near the start of the reading of “divination by pebbles,” I noticed the curtains behind Robin at the back of the stage were perceptibly swaying. [Note: on the video-recording the curtains are off camera, invisible.] And I could hear a wind, rushing up outside and whistling, heavily, under the doors. It was a calm night, and in addition to these two closed doors there were two series of plate glass doors closed at either end of the hall between all of us and the outside. Elise Ficarra and another woman working that night – Erin Wilson, was it? – were each standing at one of the double doors and both later described their sense that someone was out in the hallway outside the auditorium trying to cause trouble, and they both had the instinct to hold the doors shut, to keep whoever it was outside from coming in and making some kind of disturbance. Robin reached a point in the poem that I remember as “the voice of the 26 letters thunders in the alphabet and the diaphanous heart is at the door” – and wham! both doors burst open, and the wind or winds die down, and that’s it. The curtains stop swaying, the wind’s all done with. Then the end of the poem. Then the bluebird song, played twice, and the end of the night.

After all that I walked on stage and in the audience buzz of the aftermath told Robin what happened, and he had no idea. “Both doors?” he asked me. “Well, that would be Robert and Jack!! Oh, how I love to conjure spirits when I read.” Not everyone was aware of what had happened. David Farwell, Robin’s partner, definitely was aware, and said so, and so was Susan Thackrey. And Elise at the door and – was it Erin? – at the other door, the doors had been pulled out of their hands as they tried hard to hold them shut. No mistaking, something was happening, had just happened, and we were in it. It was there, in response to the poem or to Robin being on stage or to the occasion, stirred up, audibly and visibly and palpably present – that was an actual wind, “out of nowhere.” And then gone, calmed, not there anymore.

The poem, as it’s published two years later, 2006, goes like this:

divination by pebbles

come on, try it, one pebble,

two pebbles, three pebbles,

four dropped in the pond

among the goldfish

there the logic went

there click the dear dice

of a life’s swim for it

1001 letters of the alphabet

thunder in our footsteps

and the diaphanous heart

is at the door on the edge

of it here ––– there ––– where –––

then ––– when of it

for James Joyce

17 February 2004

Robin hadn’t mentioned James Joyce that night, maybe the afternote was added later. Though I remember from one of what seemed the many versions of his talk on what he termed “the irreparables” – that which can’t be re-paired, undone, and is devastating (in the “definitive” published version of the essay he calls it “the destruction of experience, the shattered transcendentals, the current enormity” (The Fire, 107)) – a talk that he made in public on numerous occasions and in places he was asked to speak, in at least one of the versions of this talk that was turned over and rehearsed multiple times, his trying to get at what seemed ungraspable, elusive in the extreme (and I’d worked, along with Michael Smoler, who’d encountered Robin at Naropa when we were all there one summer, at transcribing from tape at least two of these versions of “the irreparables” talk), there was an allusion to Joyce in Finnegan’s Wake naming the voice of God in thunder. I remember digging through Finnegan’s Wake trying to find what he could be talking about, and landing somehow on this gargantuan “thing” of letters:

U l l h o d t u r d e n w e i r m u d g a a r d g r i n g n i r u r d r m o l n i r f e n r i r l u k k i l o k k i b a u g i m a n d o d r r e r i n s u r t k r i n m g e r n r a c k i n a r o c k a r !

That’s about as hard to type as it is to say. And then Joyce writes (Finnegan’s Wake, 424):

– The hundredlettered name again, last word of perfect language.

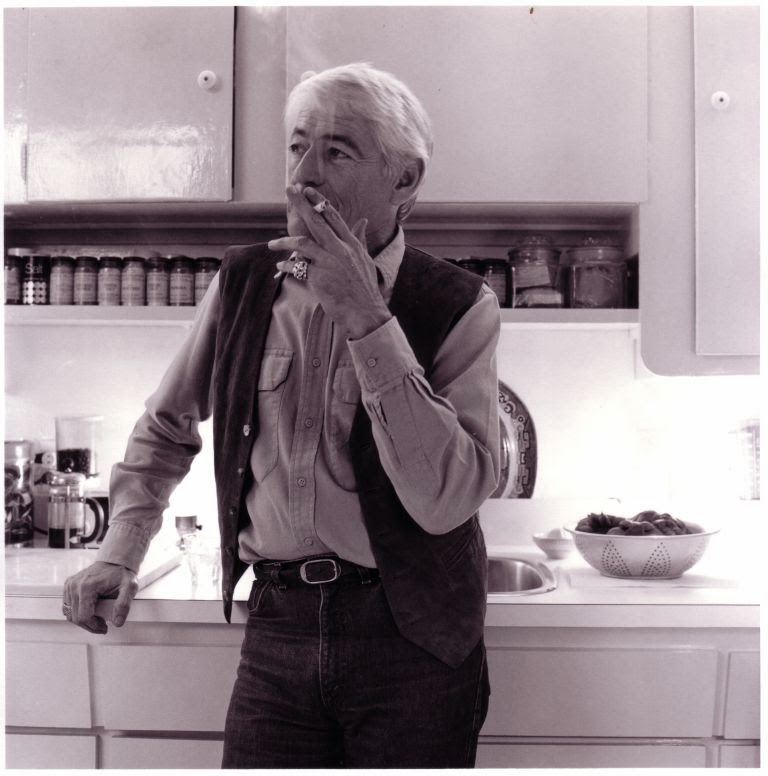

Blaser in his kitchen, Vancouver, photo from The Capilano Review site.

It isn’t there in the “definitive” published, and less erring (in the sense of wandering and maybe in other senses) version of Blaser’s essay, that Miriam Nichols edited, included in The Fire. I remember it being described in the cassette-tape recording I heard it from as “the voice of God in thunder,” and Robin laughing his laugh, “Oh, I love it,” as he tried and failed to read it from the Joyce. And it’s hubris maybe even to allude to such a thing in your poetry – “1001 letters of the alphabet / thunder in our footsteps” – what is that, that reach, that sudden hieratic note out of the ordinary?

In Sept 1903 the William Randolph Hearst Greek Theatre opened at UC Berkeley with a student production of Aristophanes’ “The Birds” done in Ancient Greek.

The first time I spent any time with Robin Blaser we walked through the U.C. Berkeley campus from the Durant Hotel. He liked to stay there because he’d stayed there his first night in Berkeley in 1945, arriving out of Idaho, after schooling at Northwestern, outside Chicago. We were walking the campus grounds in May 2000, the new millennium, somehow 55 years later. At the university’s Greek Theatre on the hill I was shown where “we held séances” there on the ground level in front of the stage with the amphitheatre seats arrayed out from the center. Robert and Jack, and Robin, and who else? At the sports stadium next door college boys were practicing – football? in May? – and Robin saying, “Oh, I do like to admire the athletes.” And we walked down past the campanile, next to one of the halls where he told me “There used to be lines in the basement for blowjobs! We didn’t go in for that.” Did we walk downhill off the campus as far as the house at 2029 Hearst Street where séances were also held, and where Duncan had “received” the Medieval Scenes, his and their first experience of a “dictated” poetry? A voice out of somewhere else, from “the outside.”

Whatever happened that February night in 2004 during Robin Blaser’s reading of “divination by pebbles,” four days after the poem was written to be delivered to us, something happened, it was there and we were there, some of us, who were aware of it, and there’s no way to explain it away. There wasn’t any wind that night, outside, until there was that wind that started whistling and moving the curtains around, built up and roared until it burst open both doors of the house. I’d been in a “real” wind once that did that, on the Gaspé peninsula, right out at the tip at land’s end, in a little cabin at night, exposed to the Atlantic. And then I read in André Breton, in a book I’d brought along on that trip, how he’d run into the same wind in the same place, during World War II when he was living outside France in exile in New York, and had traveled north into Canada to get out of the city. This wasn’t an Atlantic wind, you know, in San Francisco in Knuth Hall, and it wasn’t a Pacific wind either.

♦

The poems from tape we played that night by Duncan and by Spicer were, if I recall correctly, Duncan’s “Often I am Permitted to Return to a Meadow” – his signature song, if he has one – recorded for The Poetry Center in 1959, and the last part of Spicer’s reading in Vancouver in May 1965 from his Billy The Kid. Mysteriously or not, that poem isn’t up at PennSound with the other 1965 Spicer material, including his three Vancouver lectures, along with some of the poetry he read to accompany the lectures, and his talk at Berkeley. Blaser also read there, in Vancouver, in May 1965, from The Moth Poem, which is up at PennSound. (Viz Peter Gizzi’s note in the Lectures, the right date for this reading is May, not June as PennSound has it. Spicer’s three lectures happened in June.)

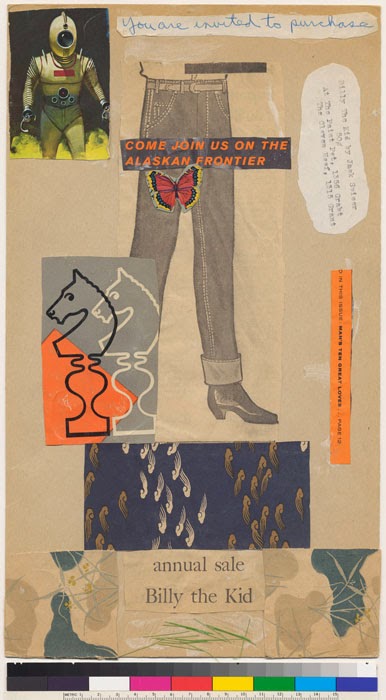

Collaged poster by Jack Spicer for Billy The Kid, Enkidu Surrogate, 1959 – Duncan and Jess’s press, Stinson Beach, CA.

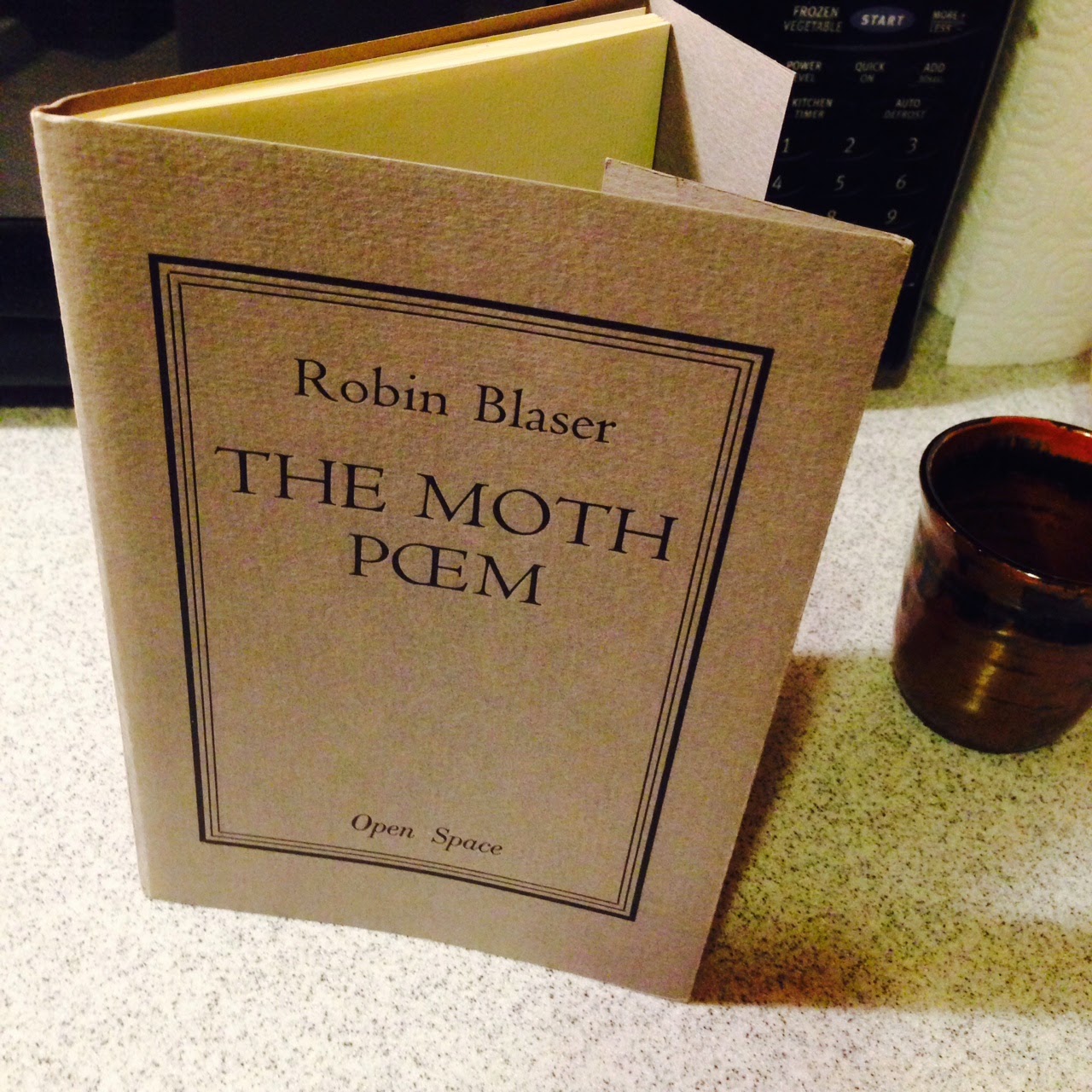

Blaser’s first book, The Moth Poem, Open Space, San Francisco, 1964; printed by Graham MacIntosh.

Duncan’s poem speaks to “a disturbance of words within words,” to “a given property of the mind / that certain bounds hold against chaos” – the emblem of the poem, and of the book, figured in Jess’s cover collage that got relegated by Grove Press to the title page, a “secret” seen “in a children’s game / of ring a round of roses told.” That game was supposed to call back to the plague time, “ashes, ashes, we all fall down” – and was at least still played by kids when I was a kid. Blaser’s “divination” poem goes, kid-like, “one pebble, / two pebbles, three pebbles, / four” – that I twice mis-typed “people” for “pebbles”. The recording of Spicer’s Billy The Kid, we’re at the New Performance Gallery in Vancouver, May 1965, opens with Robin whispering “excuse me Jack” and Jack replying “Sure thing, help yourself” as Robin pours himself a glass of water, maybe just having finished The Moth Poem? It’s dry in the landscape of Billy The Kid too. There’s a gap in the recording, a tape being turned? and some of the poem is lost. Whole sections from the end of part I, after “Not even the birds know where they are going.” He comes back, Spicer’s voice does, for the poem’s last sections, V through X.

IX

So the heart breaks

Into small fragments

he reads, when the poem reads “small shadows”

Into small fragments [small shadows]

Almost so random

They are meaningless

Blaser says at the start of his 1965 recording of the The Moth Poem, “I’m very glad that I have a chance to read The Moth Poem again, I made so many mistakes when I read it before, changes of word and so on, we’ll try.”

Like a diamond

Has at the center of it a diamond

Or a rock

Rock.

Being afraid

Love asks its bare question –

I can no more remember

What brought me here

Than bone answers bone in the arm

Or shadow sees shadow –

Deathward we ride in the boat

Like someone canoeing

In a small lake

Where at either end

There are nothing but pine-branches –

Deathward we ride in the boat

Broken-hearted or broken-bodied

The choice is real. The diamond. I

Ask it.

As if to ring home the distinction, “the choice,” there’s a palpable pause in the reading from the tape, the voice breaks, stuck, then swallows, after “Broken-hearted”; broken-voiced just before “or broken-bodied”.

“Jack was right, poetry is the boat” – where does Duncan write that?

A NEW POEM (for Jack Spicer)

You are right. What we call Poetry is the boat.

I’ve remembered it in another tense, when Spicer’s still there, present tense, in Duncan’s poem, “You are right” – he isn’t gone yet, at the time of these poems in Roots and Branches, the “Windings” section, dated 1961–63.

The first boat, the body – but it was a bed.

The bed, but it was a car.

And the driver or sandman, the boatman,

the familiar stranger, first lover,

is not with me.

You are wrong.

What we call Poetry is the lake itself,

the bewildering circling water way –

having our power in what we know nothing of,

Duncan’s poetry moving by what we decided in class is a poetic logic, apart from the rhetorical logic of argument; one that knows to cast itself in both, or more, or the other, direction/s.

that is not mine, but is a made place,

that is mine, it is so near to the heart,

They don’t rule each other out, these rulings. Spicer’s “small lake” – if it is the poem – “the perfect poem” with its “infinitely small vocabulary” (After Lorca), then these last poems of Blaser are trying that “infinitely small” territory?

… at the door on the edge

of it here ––– there ––– where –––

then ––– when of it

The long dashes he uses you have to make with an em-dash plus an en-dash, as substantial, their spacing, as the words they separate, or stretch across between. His “divination by pebbles” turns out to be the penultimate poem in The Holy Forest in its completed version, published 2006. The last poem in the book falls on the next page, that poem’s verso, as it were, and reads in its entirety

language is love

Robin Blaser

2004

It’s as if, either his “signing off” on that statement stopped the book, nothing more to say, following the visitation stirred up by the prior poem’s being read out loud, and its doing what it did – incanting, spelling – raising that wind, whatever it was, whatever it “means”; or, the wind stirred up with

there the logic went

there click the dear dice

of a life’s swim for it

in the poem’s palpably successful conjuring of spirits allowed for something as evidently simple and, at base, irrefutable as “language is love” to be asserted as “last words”. So that the conjuring could be said to have stopped him, that’s enough, I’ve managed to write it, to spell it. The funny thing about Robin Blaser is, contemporary of the other two friends, Robert Duncan (gone in 1988) and Jack Spicer (gone in 1965), he could still, for years, keep trying to have “the last word.” If the last word’s a tautology (“love is language” too), then the work, his Holy Forest, even if there are five years of life to live after early 2004, can spin on itself, on a dime, like the diamond.

I

Ask it.

There’s one more thing to bring in here, having to do with Spicer’s question, posed, in Billy The Kid. What, after all, is the question – or “choice” in the poem’s term, that “is real. The diamond.” – ?

Broken-hearted or broken-bodied

The choice is real. The diamond. I

Ask it.

This one more thing is the “answer” provided by Spicer’s “student” and, yes, friend George Stanley, in his “infinitely small” vocabulary’d, untitled poem.

My heart is broken permanently.

It works better that way.

“Broken-hearted or broken-bodied” – it’s posited as a real choice when an observer in Spicer’s last weeks, the time of his reading of Billy The Kid, of his lectures and readings in Vancouver in June 1965, and his heading home with weeks to live, might think the answer to be self-evidently “broken-bodied” – though in Stanley’s brilliant and “infinitely small” formulation what’s evident isn’t so easy.

August 1935, behind the Apollo Theater in New York City: Billie Holiday with left to right, Ben Webster, “shoebrush” (with guitar), Johnny Russell and Roger “Ram” Ramirez (in front). Photo and caption via Billy Woodberry.

The “deficit” of the broken heart is turned inside-out, to show its pure positive capabilities: it’s the ground of, say, Billie Holiday’s “Good morning, heartache… sit down.” A logic, again, if it is one, that’s other than rhetorical logic for argument or persuasion. Some of Abbey Lincoln’s songs, too, take a turn through Stanley’s poems – was it “Down Here Below” I remember, that gorgeous triumph from the string of songs she wrote for those exceptional later-career albums? It isn’t melancholy. It’s the blues ethos of someone who sees what is, and says so. One of the other poems of Blaser’s “Oh!” of 2004, says, yes

oh, I ask you in my grandmother’s

phrase, ‘be sensible’

where is the power of the heart –

in your breast – damn you –

not up there floating

like a careless alphabet

I keep misreading/misremembering that line of Robert Duncan’s as “an eternal conversation folded in all thought” – that “pasture” that is “a meadow” and “the field.” And how those all but last words in The Holy Forest end up, with the visitation that happened, four days after the poem was written in Vancouver when he carried it here and read it to us in San Francisco, conjuring that conversation into being, with that wind that was there in the hall outside, at the doors and then knocking the doors open, coming into the room. And how those new poems, for us, “Oh!,” became the last poems, spinning on the diamond “language is love.”

References

Robin Blaser, The Holy Forest: Collected Poems of Robin Blaser, Revised and Expanded Edition, edited by Miriam Nichols, foreword by Robert Creeley, afterword by Charles Bernstein, University of California Press, 2006.

–––, The Fire: Collected Essays of Robin Blaser, ed. with commentary by Miriam Nichols, University of California Press, 2006.

–––, The Last Supper: Dramatic Tableau, Libretto, words by Robin Blaser, music by Harrison Birtwhistle, Boosey & Hawkes, 2000.

Robert Duncan, The Collected Later Poems and Plays, ed. with an introduction by Peter Quartermain, University of California Press, 2014.

James Joyce, Finnegan’s Wake, Faber & Faber, 1939; third edition, 1964.

Jack Spicer, My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer, ed. Peter Gizzi and Kevin Killian, Wesleyan University Press, 2008.

George Stanley, A Tall, Serious Girl, Selected Poems: 1957–2000, ed. Kevin Davies and Larry Fagin, Qua Books, 2003.

Parentheticals

*Parenthesis 1: The State College campus was apparently built where it is today, at the farthest southwest extreme of the city, San Francisco’s nether reaches, owing to a “land-swap” with a developer named Arthur Stone, memorialized by way of Stonestown, “his” shopping mall “conveniently located,” ahem, a stone’s throw away from the grand new college campus, that today trades in some 30,000 students. In related rumorology, the many housing units strewn nearby to the south of the college (“Merced Village,” after nearby Lake Merced, a natural freshwater body despite appearances, flanked as it is by a golf course, country club, skeet shooting gallery, lakeside housing, etc., very near the southern end of Ocean Beach and the Pacific Ocean, not far from where the Zoo resides) eventually counted among its major money-bags investors one Leona Helmsley, indicted in the late 1980s for all kinds of criminal real estate and tax-fraud scams. Parenthes is over.

Return to Reference.

**Parenthesis 2: While we’d known Wystan Hugh Auden had a place in the recollected narrative of the early days of the Poetry Center, we had no recorded evidence. Cataloging gathered up from the 1970s forward showed no sign of any Auden on tape at SF State. At least into the 1960s it seems that open-reel master-tapes in the collection were loaned out for classroom use, and obviously some tapes had walked. On the shelves, e.g., there’s a numbered space for the Allen Ginsberg portion of the Six Gallery Re-Creation Reading conducted in Berkeley in March 1956, some months after the not-recorded Six Gallery reading that launched AG’s early version of “Howl” – we do have our copy of the open-reel tape of Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and Michael McClure, all introduced by emcee Kenneth Rexroth, but no Ginsberg. The recording is out there, featured in the Rhino Records boxed CD/cassette and now, yes, MP3 set Holy Soul Jelly Roll; the best online source for Ginsbergiana is likely at the Allen Ginsberg Project, set up by Bob Rosenthal and ably manned today by dear Simon Pettet. As these things happen by accident, when Jeff Davis of North Carolina not so long ago visited and had a short tour of the Archives “vault” he looked up and said “what’s that?” Among a loose unsequenced cluster of taped duplicates was a tape-box marked “W.H. Auden on ‘The Hero in Modern Poetry,’ October 11, 1954” that we’d never seen before – and by all appearances it hadn’t been seen, or heard, for many years. The digitized version of Auden’s lecture is soon headed online, once we clear it with the Auden Estate. Thanks to Jeff Davis’s keen eye for stray hand-lettering.

Return to Reference.

***Parenthesis 3: You can still come on claims that poets Kenneth Rexroth and Madeline Gleason were founders of The Poetry Center at San Francisco State. Those versions of the origin myth are specious. Rexroth claimed to have done a great many things, and he would (much later) teach classes at SF State. Madeline Gleason did found the San Francisco Poetry Guild and organized the First Festival of Modern Poetry in April 1947, which should rightfully get cited as antecedent of the Poetry Center reading series. No doubt these San Francisco poets and others, Robert Duncan looming high among them, played a role (cf. the encouragements of Dylan Thomas and Auden) in wanting and advocating for the founding of a Poetry Center. And Ruth Witt-Diamant was the only person among them in any position to actually pull off the institutional coup of establishing such a center within the State College. It had to be done from the inside, with institutional support along with the will to secure funding from inside and outside, and to be committed for the long haul. It is crucial that Ruth W-D was a friend of the poets; more on that at another time.

Return to Reference.

****Parenthesis 4: Jonas Mekas’s brief soundless footage of a New York reading at The Living Theatre, dated 1959, featuring Frank O’Hara, Allen Ginsberg, Ray Bremser, and LeRoi Jones surfaced online recently (with Jonas adding as soundtrack a later, 1960 reading of AG reading “Sunflower Sutra”), the rare moving images poignantly present in the wake of the January 9, 2014 passing of Amiri Baraka.

Return to Reference.