These are a few of the ones whose names we know. Carlos Oliva shot by Los Angeles Sheriff’s Deputy Anthony Forlano. Alex Nieto shot by a San Francisco cop the Chief of Police refuses to name. Israel Hernández tasered to death by Miami Beach cop Jorge Mercado. John Crawford III shot in Walmart by Beavercreek cop Sean Williams. Rumain Brisbon shot by a Phoenix cop whose name has not yet been revealed. And we could go on: Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice. And we could go on.

We are speechless.

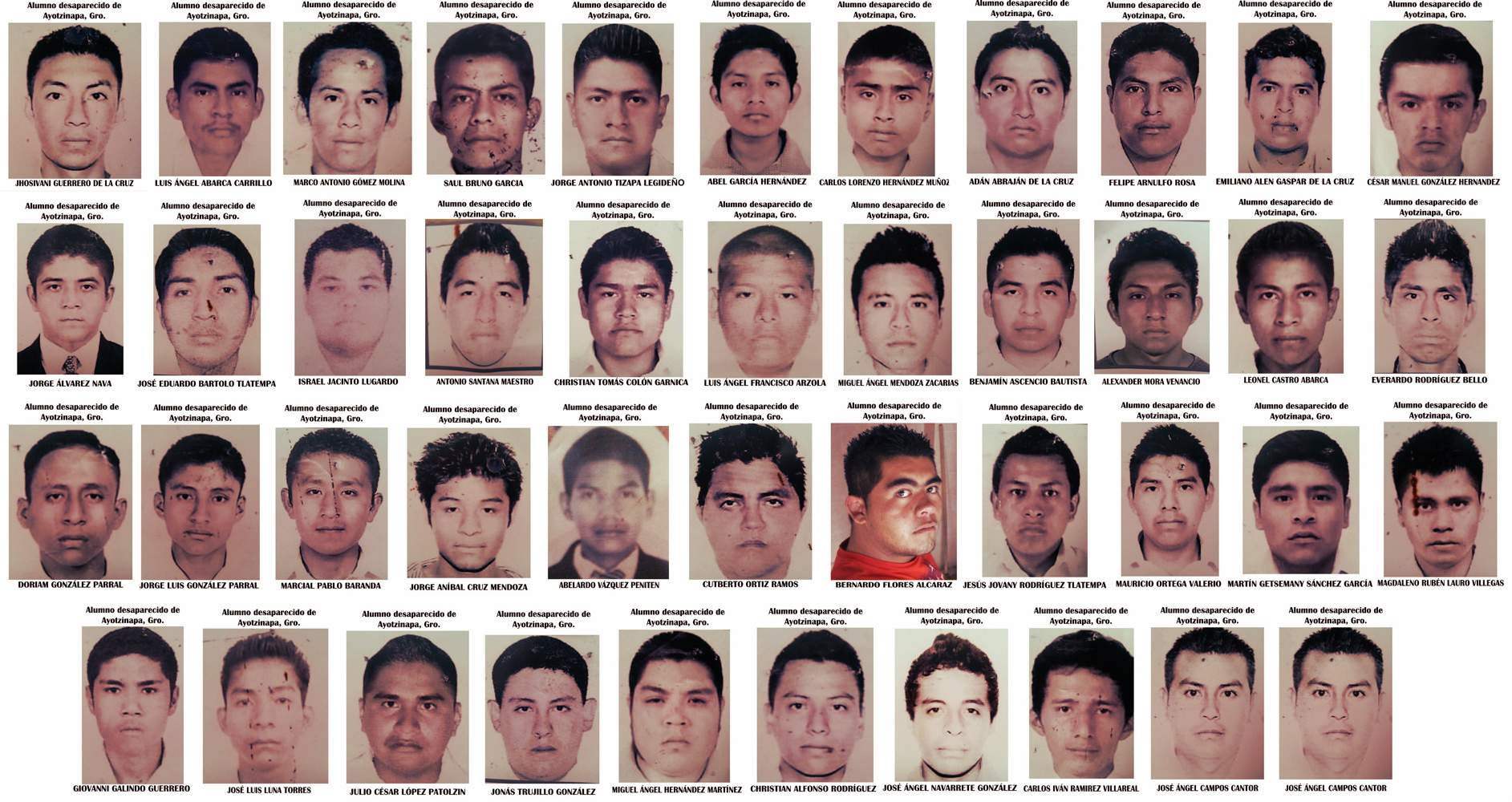

These are the names (and faces) of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa who were disappeared by Mexican police forces:

43 whose names we know. And there are over 300,000 dead and disappeared in recent years in Mexico alone whose names we cannot speak, but surely those who love them can. And do. And get silence and impunity in response. We are speechless. And the list of catastrophes and violence is never-ending—not just in our immediate regional neighborhoods and in our border cities full of borders, but farther away as well, in that way that distance can crowd very near: Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Sudan. And yet, each person is one person as Raul Zúrita reminds us (through Daniel Borzutzky):

The apocalypse...is not when the world ends; it’s when one single person is killed. The entire universe becomes deformed when one single person is tortured.

It is each person. Each name that we have. Each name that we do not have. It is the horror of one person in suffering in this instant. The terror of one person whose suffering has fallen out of view. The shocking isolation of one person facing a structure of power that refuses their own personal humanity. It is on the level of one. And it is simultaneously on the level of dozens, of hundreds, of thousands, of millions, of communities and societies that have also been torn to shreds over centuries. Asunder. Ragged. It is an overwhelming collectivity across time and the singularity of the human experience in the now. It is both of these, and it is the necessity to keep both in mind and body constantly.

Our thinking has (along with most of the people in our social networks, née communities) been subsumed by thinking about the most recent round of racist and neoliberal violence. The violence and impunity and brutal structures of power imbalance that leave us speechless. We are writing these paragraphs in December 2014. By the time you are reading this, how many more names known and unknown? How many more speechlessnesses? Time billows and slides. There is no measure.

We are forever in this space of impossibility in culture and impossibility in language. This space of rampant dominance and dominant rapaciousness. The space of both and. Forever facing the impossible space of transfer, of transposition, of making something else happen than what is happening. The space of simultaneously recognizing and resisting, as Don Mee Choi reminds us:

My translational intent has nothing to do with personal growth, intellectual exercise, or cultural exchange, which implies an equal standing of some sort. South Korea and the U.S. are not equal. I am not transnationally equal. My intent is to expose what a neocolony is, what it does to its own, what it eats and shits.

The discourse of “personal growth, intellectual exercise, or cultural exchange” is expired (caduco). If it ever really was valid (vigente) in the first place.

We are not growing, exercising, or exchanging. What are we doing? What is there to do? We are not equal. We can advocate for equity, but there is no equality. And we are not equal to the circumstances that form our context.

We are speechless. We work from within our speechlessness.

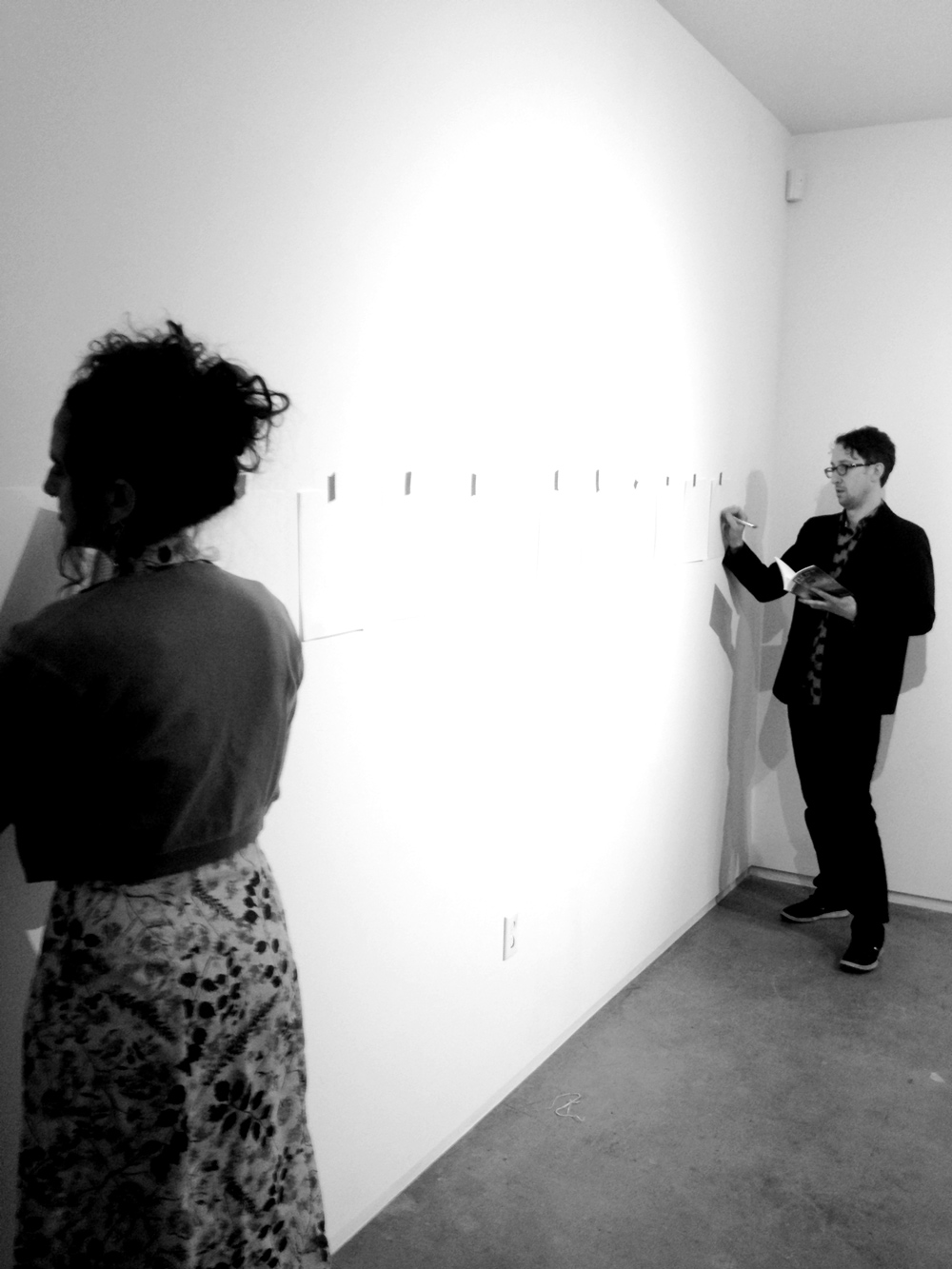

Documentation Pillar in the installation Antena @ PRH,

March – June 2012, invoking Akilah Oliver. Photo by John Pluecker.

When Rosa Alcalá invited us to do something for this issue of Evening Will Come, we were torn. In some senses, we are still torn. Asunder. The world is ragged; we are ragged. When we receive such an invitation, we ask ourselves: what is Antena? Every time we begin again, take nothing for granted. Do we imagine something new? Progress on to another iteration of something that might move our thinking or our practice elsewhere? The impulse is initially to do just that. But do we do that automatically? Do we keep pushing ourselves forward forward forward?

Art organizations tend to work this way, pushing into the next, the new, the future constantly. Which can cause some definite dissonance. We don’t want to move forward just because we can. We don’t want to forge ahead without stopping to ask questions. We ask ourselves: what are we moving toward and why? Is forward the only direction to move? What if we resist progress in favor of pondering, proliferation, protest, and pause? What is made possible in the different kinds of practice we enact? What is foreclosed? Mostly we strive to be in the world accountably, curiously, inquisitively, observationally, critically, joyously. Are there ways to be in the now, reflecting back (which is also forward) on what we’ve been doing?

Pamphlet display as part of Antena @ Blaffer installation, January – May 2014. You can find the texts of these pamphlets here. Photo by Alex Barber

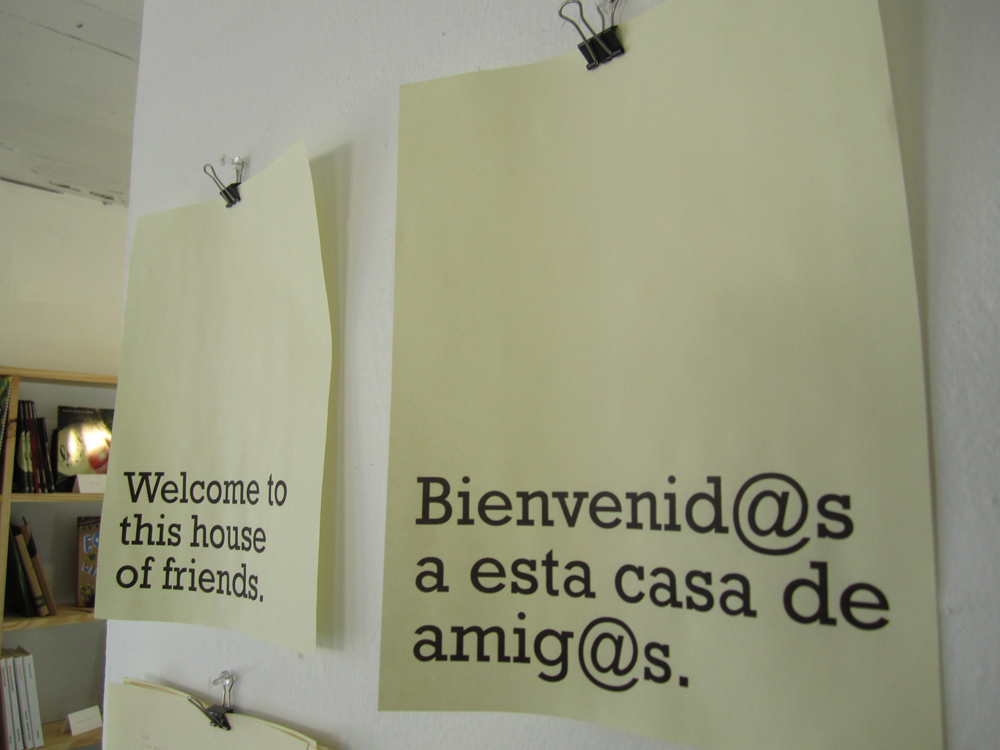

Since we founded Antena not that long ago in 2010, we have done many things. Maybe too many things, or maybe not enough things. We have done a torrent of things. A torment. A moment. We have relentlessly pursued engagement, instigation, conversation. Done interviews and workshops and presentations. Collaborative interpreting and multilingual space building. Publishing. Language justice advocating. Collaborative translation. Writing. Bilingual programming. Installation-designing. Installation-making. Installation-deinstalling. Installation-destressing. Restressing. Book-scheming. Residency-dreaming.

In 2010 when we founded Antena, our context was a different (same-same-but-different) maelstrom of violence and anti-justice. Earthquake, destruction and deaths in Haiti and the neoliberal equation that meant subsequent thousands killed for lack of food and disease. The BP Horizon oil well gushing thousands of gallons every day into the Gulf. The peak of Calderón’s (and Obama’s) dirty war (née drug war) in Mexico. The ongoing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The endless abstracted “overseas contingency operations” (née global war on terror) with their very concrete effects on drone-curtailed civilian lives all over the globe. Increasingly intricate forms of incarceration and interrogation, and radical curtailments of civil rights at “home.”

En fin, it was an awful time. It is an awful time. We don’t remember this to make ourselves or you depressed. Or to be preachy. Or to founder in the dead end that all this death represents. But rather to think about what Antena meant then and what it means now and how it makes meaning or means making in a context crowded with too many meaningless and meaningful impossibilities.

We are speechless, and speechlessness has made us want to listen. To locate ways to amplify the voices of thinkers who might not otherwise be heard. To work in a way that incites radical listening as a form of political action: what is being said elsewhere, elsewise, is necessary for us to hear here. We urgently need other ways of talking with one another, other ways of forming sentences and articulating ideas, as tools for organizing, protesting, blockading, shutting shit down, and rebuilding.

From speechlessness and outrage: translation and interpretation and the reverberations those modes of transfer make possible.

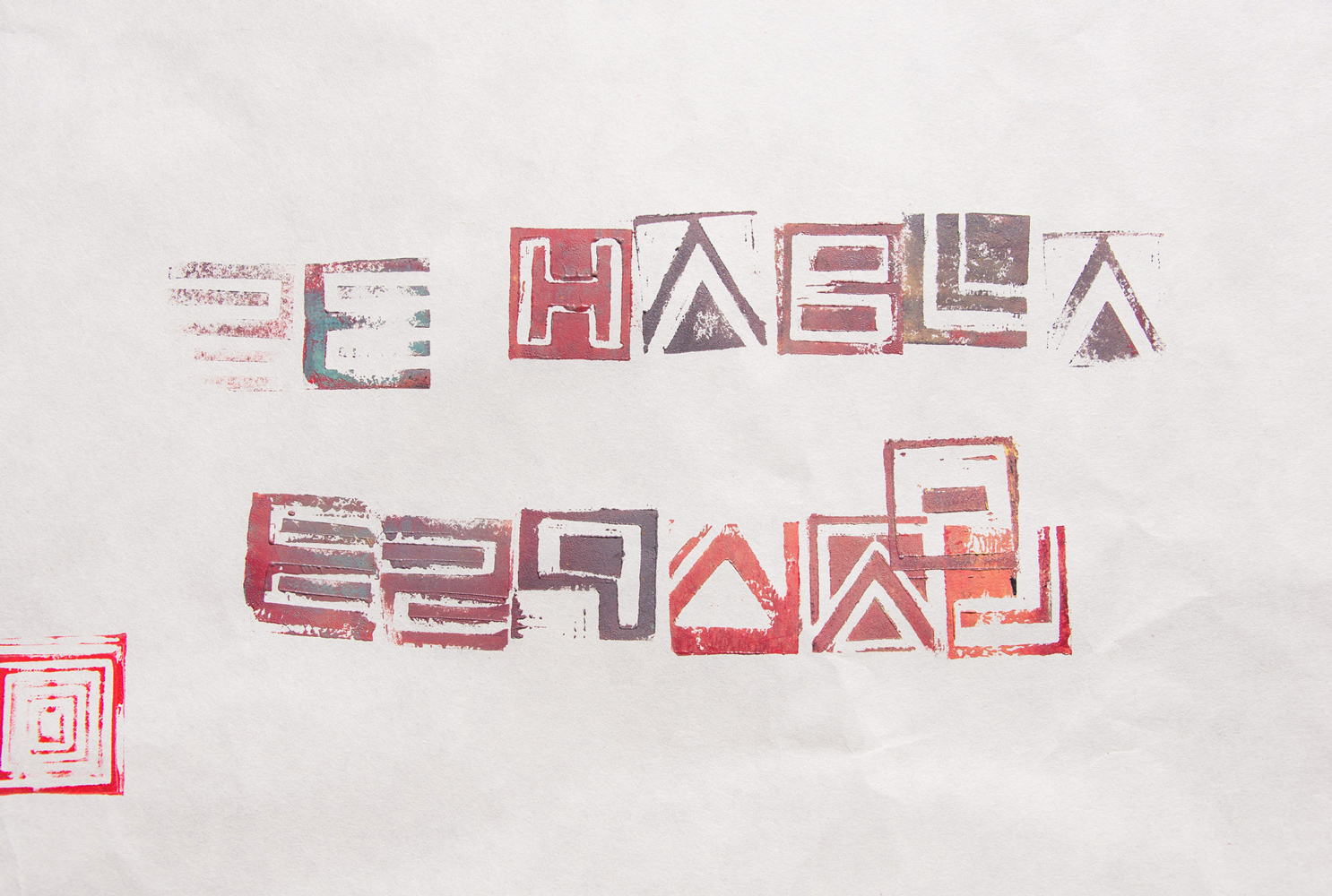

Detail, large-scale hand-printed piece made when Nuria Montiel turned the AntenaMóvil into an ImprentaMóvil during the Antena @ Blaffer Encuentro, February 2014. Photo by Pablo Giménez Zapiola

Translation and interpretation, in all the ways we have come to understand them over years of engaging with other artists’ work. And translation and interpretation in all the ways we can redefine them to constitute other forms of listening and other forms of speech.

We don’t do this work as an “intellectual exercise,” though it does provide a workout. We don’t do it believing that anything as simple or as idealistic as “cultural exchange” is possible. And communication is never on an equal footing. One person assumes they are entitled to be in a space; one person invites another in. One language is a tool of world domination; another language is marginalized. A language functions simultaneously as marginalized in one space and marginalizing in another. Already the imbalances are huge. Always. Can we think outside those imbalances while still acknowledging them? Can we refuse to respect them while still recognizing their effects?

There is never enough time. There is always more to do. The information overload is overwhelming. The lack-of-information overload is overwhelming. And yet we go back to our practice as interpreters and translators. To the space of slow time between languages, between ideas, between phrases, between persons. Putting our energies and our work into those spaces. Putting our bodies in the line. In an interview with PEN, Don Mee Choi says “My politico-aesthetic stance and practice as a poet and translator is “illegal” and will likely remain so.” And:

Lauren Cerand: Where is the line between observation and surveillance?

Don Mee Choi: Surveillance is obviously about discipline and control. I like to think that observation is the line itself, an “illegal” line.

Where are the differences between “cultural exchange” and “cross-language” or “cross-cultural” work? “Exchange” suggests a focus on an object or currency, a thing that is traded or transferred from one context to another. “Crossing” suggests a mobility or a transit, a body or bodies in the balance, in the space between. An exchange can be completed: transaction over. Crossing is a process, an atmosphere, a mode. It doesn’t move from there to here, it’s in the between. How do we work if we are going to work in that space, in that traffic?

Antena interprets at a rally of the Caravan for Peace in El Paso, 2012. Photographer unknown.

In 2012, we worked as interpreters for the Caravana por la Paz con Justicia y Dignidad. Interpreting and building multilingual space across the country with a committed team of language justice activists on the caravan. Participating in a flawed but powerful movement of human beings telling their own stories, in their own languages, and demanding to be heard. Making a presence in state and municipal offices, in public spaces, in community refuges.

Antena interprets at a Caravan for Peace event at La Placita in Los Angeles, 2012. Photo by Bertha Rodríguez.

It was the summer before the election of Peña Nieto. Calderón was on his way out. Though we can say “there are over 300,000 dead and disappeared in recent years in Mexico alone,” the numbers of people disappeared in Mexico are really beyond counting. The numbers of people killed are equally hard to count. And yet, this lack of clarity is only more reason for action, for interpretation.

Our interpreting during the Caravan was both speech and not-speech; interpretation is more a form of listening than a form of self-expression. When we interpret, we work in service of the message, and in service of expanding the possibilities for cross-language and cross-cultural communication in a particular room, rather than in service of our message, or our participation in that communication. What is the nature of the communication an interpreter enacts?

To listen closely to what someone is saying and repeat it accurately (yet always differently) in another language is a specialized form of speech.

…

Interpreters do not repeat the words of another person mindlessly, mechanically. Interpreters are not parrots. Interpreters repeat the words of another person mindfully, humanly. Compassion, humility and selflessness drive our practice. Interpreters do not mimic; we embody. (From Manifesto for Interpretation as Instigation)

As interpreters, our words are not our own. As translators, our words are not our own. Though our words are uniquely ours—or rather, our way of following someone else’s words is distinctive and unique. Speechlessness can, in some sense, be addressed—or inhabited differently—by speaking from within someone else’s speech.

In the world—in interpretation—we must listen. And speak. And be speechless. And be in speech. And allow language to pass through us. And notice the texture and shape of language, how it creates realities. How it creates potentialities.

The AntenaMóvil at the Social Practice Social Justice Symposium at Project Row Houses, January 2014. Photo by Jen Hofer.

We made our first installation in 2012, at Project Row Houses. Concurrently, we began to think about what our political and occupational practice as language justice advocates and social justice interpreters might have to say to our poetic practice, and about what poetry might have to say to interpreting and language justice work. We wrote about that experience in The Conversant. In 2014 we did an even larger scale installation at the Blaffer Art Museum at the University of Houston.

We made a short video that shows some of what we did (and also how tired we were by the end of it!)

We convened conversations and performances and workshops and class visits. We were available in the space every day the museum was open to talk with people about the books and artworks in the installation. We rode the AntenaMóvil to community events.

Tony Macías, interpreting for the Encuentro: Antena @ Blaffer. Photo by Pablo Giménez Zapiola

As part of the installation, we organized a series of bilingual spaces for conversation and reflection. Some were part of the Encuentro we organized with all eleven of the artists who participated in Antena @ Blaffer.

Bilingual conversation among eleven of the artists who participated in Antena’s Encuentro, with Sandra Tapia interpreting. Photo by Tony Macías.

Others were experiments in interrupting predictable distinctions between what happens in an aesthetic or literary space and what happens in spaces for political organizing. For instance, as part of a Houston-wide performance festival, we launched the bilingual book Antena co-produced with La Colmena Domestic Workers’ Collective, with a bilingual reading and book celebration at Blaffer that also entailed interpreted conversation circles led by members of La Colmena, focusing on issues of central concern to domestic workers.

Members of La Colmena Domestic Workers Collective facilitating a conversation circle about domestic workers’ narratives in the Antena @ Blaffer installation, with Alejandro Márquez interpreting. Photo by John Pluecker.

All of these were efforts to collect evidence of what bilingual space can do, of the kinds of thinking and interaction that are made possible in spaces where the dominance of one language over all others is not taken for granted. Radical listening: what can be made there?

It did not work as “cultural exchange.” It did not work as “intellectual exercise.” It worked as a way of working. A way of learning. A way of lingering in not-knowing. Remaining ragged.

It worked to illustrate a continuing failure. The continuing failure of communication to bridge the ever-widening gulfs of income and education. We live in a system set up to further oppression and violence, to institutionalize injustice and inequality. We can’t be so naïve as to think we might end this system as interpreters and translators, facilitators of multilingual space.

And yet, these bilingual spaces make “language dominance” visible. We discuss the place of the tongue in creating neocolony, neowarfare, neooppression. We invoke language justice. We ask: what is justice in language? How can language be a tool for enacting a kind of justice we have not yet seen, can only just imagine?

We convene the spaces we want to inhabit. We are living a laboratory for undoing the ideas and structures of language dominance. We do not always succeed. We don’t necessarily want to succeed. The spaces we create are experiments. Without these spaces, English gets off the hook.

How do we work so that English remains on the hook? And so that we remain there, as well? What does writing-by-listening look like, sound like? How do we use English to undermine the dominance of English? We are interested in thoughtful risk-taking as a way to destabilize privilege. We are interested in purposeful vulnerability as a way to resist the smoothness in language that signals a model of singularity, uniqueness, and expertise that we believe is ethically and creatively empty. And so we do experiments with interpreting and translating practice to push ourselves to think through the possibilities of using our speechlessness to generate other forms of speech.

Antena performing improvised poem-making at the opening of Antena @ Blaffer. Photo by David Leftwich.

In this form, we make poems collaboratively by interpreting back and forth to each other. We begin with text in Spanish and text in English. We read fragments of text aloud, and we improvise. We interpret longer and longer sequences back and forth between Spanish and English, creating a context where error is not just welcome, but inevitable.

This performance of interpretation-generated improvised poem-making is something we devised after we wrote our Manifesto for Discomfortable Writing, which was originally published in Floor journal. We realized we needed to figure out a mode that would be discomfortable for us, and try to work in that mode. There are many discomforts involved in our practice of interpretation-improvisation, as is evident from this video we made documenting an early iteration of the form. It feels strange to undo some of the strict guidelines we follow when we interpret professionally, for this alternate, resolutely anti-professional manifestation of the practice. “Accuracy” in an improvised poem is entirely different from “accuracy” in an immigration hearing, a court trial, a medical appointment, or a community meeting. When interpretation becomes a generative strategy for poem-making, we don’t attempt to correct our mistakes, we attempt to use them to spark other language, other mistakes.

Antena performing improvised poem-making at the opening of Antena @ Blaffer. Photo by David Leftwich.

We continue to think about what it means to interpret. In a pair. On the wall. Visibly, publicly. What it means to get inside found/appropriated texts and each other’s invented language and repeat it back to one another. To repeat without reproducing. Always to be different than we were a moment ago.

In the end, there is a blank wall once again. And a set of papers with notes on them. An empty space that is not empty.

The aftermath of improvised poem-making at the opening of Antena @ Blaffer. Photo by David Leftwich.

Material detritus of all our attempts to make the imbalances visible. To insist on their visibility. To fail in the process and document our failings.

And we continue to work on other projects, other experiments, other ways to make the shit more visible in a country that has always preferred to turn away from its own shit.