Uncomfortable with boundaries and linearity, and unable (now) to use only words, I wrote first out of resistance and drove myself into my own language.2 It was given to me by those whose work I have swallowed.3

[[I do not like this page. If I did not want to publish, if I did not want to “turn this in,” I would write this on a wall-wide piece of paper, and put the pieces in an order that is not sequential but webbed (or, in fact, the web would be the best place for this roving-and-with-images-writing, in the web’s feels-limitless space).]]

[Laura Hinton]: This block about expository writing, can you say something more about that?

[Mei-Mei Brussenbrugge]: I think it’s whatever my brain structures are. And I can’t overcome that. I can’t write a paragraph.

LH: Perhaps because expository writing represents a certain kind of linearity associated with a Western-type logic that your own style of poetry writing seems very much against?

MB: Yes, I think it’s the linearity—and also the voice. But I’m also interested right now in a type of discourse that is very direct and clear—‘like’ expository.

My friend Leslie Marmon Silko gave me a Courtney Love song, ‘I want to Be the Girl Who Has the Most Cake.’ It struck me as so clear and simple.1

(Frost & Hogue 47)

Writing’s initial situation, its point of origin, is often characterized and always complicated by opposing impulses in the writer and by a seeming dilemma that language creates and then cannot resolve. The writer experiences a conflict between a desire to satisfy a demand for boundedness, for containment and coherence, and a simultaneous desire for free, unhampered access to the world prompting a correspondingly open response to it. Curiously, the term inclusivity is applicable to both, though the connotive emphasis is different for each. The impulse to boundedness demands circumscription and that in turn requires that a distinction be made between inside and outside, between the relevant and the (for the particular writing at hand) confusing and irrelevant—the meaningless. The desire for unhampered access and response to the world (an encyclopedic impulse), on the other hand, hates to leave anything out. The essential question here concerns the writer’s subject position.

(Hejinian Language 41-42)

My novel needed a trajectory, which seemed to require boundedness (coherence, which is related to plot), and I was writing towards the distinction between inside and outside, the flash of present juxtaposed against the flash of memory, and then the reader would know what those two mean to each other, and how the narrator cannot let go of her sister or her past.

But the flashes weren’t working yet; they needed to be culled and sliced and pared down. More precise and surprising and making the feeling of puncture, or flash, that’s what I always imagined it would be, from the beginning. Story/ FLASH! / / FLASH!.

I was struggling with the “encyclopedic impulse” and could not cut (I thought I could, sliced out 8,000 words—but not enough). Now, I can cut.

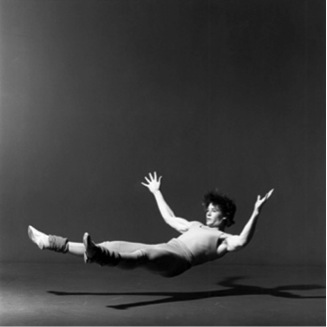

Perfect illustration [speaks my imagination]—I want this for my novel:

(Parsons Dance Company, “Caught”)

(idanceshow.blogspot.com)

The effect is a stunning suspension of weight in which the dancer appears to fly through the air, devouring space before magically returning to rest at center stage.

(Alvin Ailey)

I wanted (want.) this “stunning suspension of weight,” this “devouring of space,” and then a pause (gap, breath, no seam between the pieces) and comes the flash of the next moment, when the dancer is suspended in mid-air again, elsewhere on the stage, in another position, and you don’t know how she got there. And this would be the sort of writing that is “very direct and clear,” that Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge describes above. Direct and clear and punctuated.

Parsons’ strobe flashes are the points of Hejinian’s pleats—the folds we see—and the darkness is what she has left out, which we can only surmise. We make connections between the pleats, which are only our imagination of what’s in the gap (darkness where the leap occurs, what’s unsaid).

(Threads Magazine) And there is in this, that same simplicity, which I crave.

(Though in the background there is all the work of practice, coordinating of the strobe light, choreography of the dance, the practice, the honing of muscles, the critique of the choreographer, says try this, or do it again. The simplicity is undergirded by much planning and thinking and work. It is work. I crave what looks like simplicity [PRECISION] spare in its final effect.]

One begins as a

student but

becomes a friend of

clouds

Back and backward, why,

wide and wider. Such that

art is inseparable from the

search for reality. The con-

tinent is greater than the

content. A river nets the

peninsula.

(Hejinian My Life 119)

“Art is inseparable from the / search for reality.” This is the thing. And on the page I want a representation of reality—translation of a way of thinking—how to represent what is in my mind. (I have a splash of Bernstein in me, craving for the sound piece, art installations I designed, which can speak better than the language, crave to bend language to make it work, to speak for something else, to use the hands to sew instead of to type (and to sew is to write, all the same):

We might begin with Anne Bradstreet’s famous line: ‘I am obnoxious to each carping tongue / Who says my hand a needle better fits.’ That sentence establishes a creative tension between pens and needles, hands and tongues, written and nonwritten forms of female expression, inviting us not only to take oral traditions and material sources more seriously…but also to examine the roots of the written documents we take so much for granted.

(Ulrich 202)

This is Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (winner of the Pulitzer for her work on reading women’s diaries as historical documents), arguing that most women did not have the chance to write. That most women were not privileged enough to stitch images of Harvard University, but instead made shirts and other necessities (207). She is a historian, looking back. But this tension still exists—the women who make fiber art less respected (often, they have told me) than the women who paint. But if a man takes up fiber art, he is viewed differently (a conversation that has been taken up lately about “women’s fiction”) (Meg Wolitzer’s article and the VIDA counts).

Jen Bervin, writer-sewer, in Brooklyn, exhibits her work as much as she publishes it. She embroiders, or weaves, or stitches Emily Dickinson’s poems into tallied lines. I am thinking about labor—female labor, sewing, a response to Ulrich, a response to Marx and factories and underpaid women in terrible conditions around the world (women who make the fabric I use—a guilt inherent in this, a connection to the need for ethics in our work.) I am in this conversation with them.

I came into this because words couldn’t say anymore. I needed the tactile, the slide of fabric underneath my hands, steady sound of the sewing machine, something made—complete—in the end. An object to hold, colors to lift.

Sewing became precision of expression.

Before I lost words, I wrote a series of things in Johnson, Vermont: the words were stranger shorter pieces than what I’d written before, and later, after I made the images, the words wanted to be paired with the images. So they became The Vermont Studio Center Experiments. I was with visual artists during the residency in Vermont, and they talked about their work and could do things in their work that I loved—they were raucous and brave, louder than the writers in every way—smoking and drinking all night, slugging to their studios to get their hands into colors, to collage and paint and draw, to perform in black leather outfits with chains, to use saws and hammers and tear and listen to music as they worked (while the writer’s building was a hush, and there were complaints if anyone could hear anyone else from room to room). This is how the artists spoke.

[My family is full of artists, but I never thought I could do what they do. I always wrote instead. Sewing is something they never did—clothes, yes, but not as pictures. So it was mine.]

The words came from the strangeness of Walser and his pumpkin heads in short shorts, from Lydia Davis and her constrained language, repetition bound (boundedness, as a quilt) in wide-margined blocks of text. From Aimee Bender and her surrealist stories, and Kafka’s big bug, and the sound of the language came from CD Wright and Zora Neale Hurston and Virginia Woolf and Lorrie Moore and Alice Munro and Haryette Mullen and Gloria Anzaldua. I had imbibed their songness—musicality—and soaked it in for years and years. (And their sense of ownership of text, their sense of self and woman-writer, that I absorbed, too, less consciously.)

Whatever the differences—and there are many—between the clearly different art forms of quilting and writing, the ‘oral history’ on paper of My Life and the traditional pieced quilt are both specifically autobiographical texts. In the previous century, quilters frequently conceived of their work in terms of autobiographical books; they called their quilts personal “albums” and “diaries,” or even “bound volumes of hieroglyphics” (Ferrero et al. 11), books which—like Hejinian’s text—are unfamiliar and difficult to read, and require some translation. Quilts were thought of as autobiographies not only because they were the products of substantial daily labor, but also because their subject matter was often quite literally composed of remainders of the artist’s daily life (work clothes, daily wear, fancy dress) and reminders of the important occasions of that life (crib swaddling, wedding dress, mourning gown). These textiles, drawn from the clothes of people close to the quilter, transform the quilt itself into a text that incorporates, as one nineteenth-century writer phrased it, “‘passages of my life,’ ‘memories of childhood, youth, and mature years ... of life and death’” (qtd. in Ferrero et al. 34).

(Dworkin 60)

This comparison of Hejinian’s writing to the quilt is fitting, another way to make a metaphor for the ways that the strangenesses in her writing work, and to sustain the argument that writing and sewing can be studied (and made) in the same ways.

…search for reality. The con-

tinent is greater than the

content. A river nets the

peninsula. The garden

rooster goes through the

goldenrod. I watched a robin working its way on

the ridge, time on the uneven light ledge. There as

in that’s their truck there. Where it rested in the

weather there it rusted. As one would say, my

friends, meaning no possession, and don’t harm

my trees. Marigolds, nasturtiums, snapdragons,

sweet William, forget-me-nots, replaced by chard,

tomatoes, lettuce, garlic, peas, beans, carrots, rad-

ishes—but marigolds. The hum hurts. Still, I felt

intuitively that this which was incomprehensible

was expectant, increasing, was good. The greatest

thrill was to be the one to ‘tell.’ All rivers’ left banks

remind me of Paris, not to see or sit upon but to

hear spoken of….

Has the baby enough teeth for an apple. Juggle,

jungle, chuckle. The hummingbird, for all we know,

may be singing all day long. We had been in France

where every word was really a bird, a thing singing.

I laugh as if my pots were clean. The apple in the

pie is the pie. An extremely pleasant and often comic

satisfaction comes from the conjunction, the fit, say,

of comprehension in a reader’s mind to content in a

writer’s work. But not bitter.

(Hejinian My Life 119-121).

Full of songness—“Where it rested in the / weather there it rusted,” “Marigolds, nasturtiums, snapdragons,” “The hum hurts,” “Juggle/ jungle, chuckle,” “every word was really a bird.” The rhythm of the words drives the story (poem) on, the disjunctions—folds where language meets, the flash of the strobe on a moment of action that was derived from leaps and steps through darkness before the exposure we see—what Perloff says Shklovsky calls “making it strange.” Why is this word next to this one? What does the truck have to do with the flowers with the “hum hurts” with France (keeps coming up) with the bird’s song? All a song, one long narrative of flashes, leading to “an extremely pleasant and often comic / satisfaction” from these disjunctions juxtaposed: “comes from the junction, the fit, say, / of comprehension in a reader’s mind to content in a / writer’s work.” Satisfaction from our understanding of the threads that bind the flashes we see. We can’t help but see the threads that connect any action to its subsequent parts. And she feeds us these threads, builds the connections, with her repetitions—France (in this piece), ie: “we who ‘love to be astonished.”

Listen to the drips.

(63)

Her drips are his flashes.

‘A work of art,’ [Wittgenstein] observed in 1930, ‘forces us—as one might say—to see it in the right perspective but, in the absence of art, the object is just a fragment of nature like any other’ (CV 4). Here Wittgenstein echoes, no doubt unwittingly, Viktor Shklovsky’s famous doctrine of ‘making it strange,’ or ‘defamiliarization,’ with its emphasis on the ‘artistic’ removal of the object from its usual surroundings so as to recharge its potency, the object itself being ‘unimportant.’

(Perloff 11)

Thus, “The hum hurts.”

Thus:

(Parsons Dance)

Flipbook in action makes us think that every still image is not still, but moves into the next, continuous. We make a story of the fragments (stills), create action, made fresh by one strangeness beside another.

(Par Hoglund)

Every longer piece (novel, novella, book of shorts and sewing) that I’ve written is made of smaller fragments. This just happened (seemed to just happen). So the struggle is in composition of the pieces—how to arrange them. Where to leave the breaths. What to cut. What will make the best strangenesses, the best flashes, and where does each flash go to create the sense of motion.

What will make the best rhythm?

What to cut and what to leave? Roni Horn says, very Hejinianally:

Spinelli: The structure of your work is very open, meaning that the viewers can have their own ideas about a work or that they build up their own fictions. Do you mind that? And how open do you want your work to be understood?

Horn: I think people just do it. I don’t think you can ever get away from a view that isn’t half filled with a person’s desires. There isn’t any work that avoids that. But the work which is called Haraldsdóttir, which is the next book, definitely encourages it. It also exists as a separate and surprisingly different work in the form of a photographic installation called You are the Weather. I shot over 200 rolls of film of Margrét. Over the year I edited it down to 100 photographs and I sorted out all of the photographs where she is not making direct eye contact with viewer/photographer. Because as long as she makes eye contact the relationship between the viewer and the subject is nonhierarchical, as well as non-voyeuristic. You are not looking at Margrét in the traditional sense of nude photography. You are looking at this woman looking at you. The installation will consist of this persistent stare. It’s about intimacy, about conjuring this intimacy but remaining anonymous. She never reveals her identity. What you get instead is a collection of identities. You see her face one hundred times to be precise, but she never appears as the same woman. Even though she has been photographed the same way, even though there was no makeup and no direction, each sequence is extremely different. Because of her relationship to the weather, the light, the wind, or whatever was going on — she takes on this broad range of personalities. In producing this work I became aware of the fact that you are the weather.

(Spinelli)

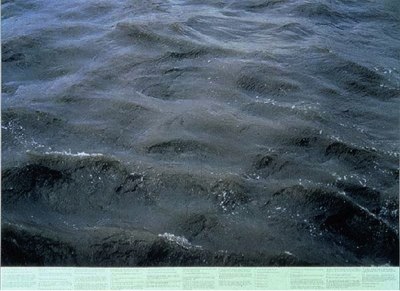

At the ICA in Boston, her response to Dickinson (sculptures of the poetry), her words-and-images:

(Mr. Dopestar)

This is the Seine, and underneath are words in numbered lists, about what happens in the Seine, how the water moves, the people who come to see the Seine. The same sense of strangeness as in Hejinian, the same sense of humor, too, in the surprises of juxtapositioning.

Language and the Visual, this is where I was drawn: Matisse and Picasso, I was finally allowed to write about them in an English class (Dr. Holland), and about Dickens’ illustrations, and how they change the sense of the story when they are included (as they are not usually). And his revisions. And how writing can change. How images affect our sense of story and relationship. How words and text speak together/to each other.

Poets give me musicality. Space on the page (I am learning this), and line breaks, and lack of resolution sometimes, or the ring of recognition functioning as plot-satisfaction does.

5.

sly as a marten, evade

natural law replace

one boundary w/another, we flow

to its edge, roll back

define this pain as content

rest—

less as wind, renew

ingathering, to leap….

(DiPrima 193)

The spaces create their own image on the page, meandering white margin, an opening. And the gaps are breaths, and the reader has to work harder to leap across the gaps, connect one word to another—to think past what is happening? to letting the words ride over and through, coalescing in some meaning (if we need meaning) in the end, or much later.

The Beats give me bravery and a tumbling rhythm, the raucous voice of the Vermont artists with the musicality like CD Wright with the structure of rolling-continuity or open, spare lines, depending on who’s speaking:

I’m with you in Rockland

where we wake up electrified out of the coma by our own souls’

airplanes roaring over the roof they’ve come to drop angelic bombs

the hospital illuminates itself imaginary walls collapse I skinny

legions run outside O starry-spangled shock of mercy the eternal

war is here O victory forget your underwear we’re free.

(Ginsberg 56)

Liberation in these lines, liberation from the restraint and oppression of “electrified out of the coma by our own souls,” to “forget your underwear we’re free.” Ginsberg’s voice is bravely his—claiming his sexuality at a time when it was a risk to do so, claiming his place as a writer among writers.

And Celan gives me clarity, the clarity of expression that Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge spoke of in her work, ‘like’ exposition (and how Celan can say it but not say it—“second level metaphor,” Peter said—but this is how survivors can speak of what’s been survived, maybe—apophasis, what’s there but not said. As WG Sebald (second-generation survivor) does in his books about the Holocaust, writing around and around the truth of it, with stories enjambed against each other and images and echoes of what happened, without saying it outright).

Into the Foghorn

Mouth in the hidden mirror,

knee at the pillar of pride,

hand with the bar of a cage:

proffer yourselves the dark,

speak my name,

lead me to him.

I am the first to drink of the blue that still looks for its eye.

I drink from your footprint and see:

you roll through my fingers, pearl, and you grow!

You grow, as do all the forgotten.

You roll: the black hailstone of sadness

is caught by a kerchief turned white with waving goodbye.

(Celan 35)

Before, I did not know Celan. His language! The clarity of it, the accuracy of his lines, images, and where the lines will end and begin. He can write of darkness, “the black hailstone of sadness,” the weight of what he has been through (its own bravery), and yet the language is its own beauty, too, even in spite of its content: “is caught by a kerchief turned white with waving goodbye.” He breaks our hearts.

There is more to say about writing and ethics, and how we are never separate from our consciences when we write, how there is a holiness to some writing—like Celan’s—that comes with survivorship, or witness, or confession. Anne Sexton holds this, too, in a different way (nothing can be compared to the Holocaust, the return to Adorno again). Reverence. For some writers, I have not just admiration but I hold their work with a sort of reverence, a quiet around their words that deserves its own space. The hush of respect, maybe.

I am approaching a declarative text, written in pieces and longer pieces, with diagrams and pictures of brains and a lot of science. Joy Castro said that she did not feel as though she was “living out loud” until she published The Truth Book2. I have always wanted that feeling. After keeping a secret for twenty-two years, and then unburdening the secret, I was given liberation. And now I will speak/piece/write/sew/draw it.

Endnotes

1From Laurel Thatcher Ulrich's ‘Of Pens and Needles.’ This piece was written at the end of Peter Covino’s graduate poetry class that included readings of DiPrima, Celan, Bernstein, Parsons, Hejinian, and Perloff.

Return to Reference.

2Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge in Innovative Women Poets, ed. Elizabeth A. Frost and Cynthia Hogue. 47

Return to Reference.

3Joy Castro said this in a classroom visit to Barbara DiBernard’s Women’s Writing of the 20th and 21st Centuries, at The University of Nebraska-Lincoln in Spring 2008; I was interning with Professor DiBernard at this time, and we had just read The Truth Book.

Return to Reference.

Works Cited

Bernstein, Charles. All the Whiskey in Heaven: Selected Poems. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010.

“Caught.” Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Online.

Celan, Paul. Poems of Paul Celan. New York: Persea Books, 2002.

DiPrima, Diane. Pieces of a Song. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1990.

Dworkin, Craig Douglas. “Penelope Reworking the Twill: Patchwork, Writing, and Lyn Hejinian’s ‘My Life.’” Contemporary Literature 36.1 (Spring 1995): 58-81. Print.

Frost, Elisabeth A. and Cynthia Hogue, Eds.. Innovative Women Poets: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry and Interviews. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2006.

Ginsberg, Allen. Selected Poems 1947-1995. New York: Harper Perennial Classics, 1996.

Hejinian, Lyn. The Language of Inquiry. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Hejinian, Lyn. My Life. Los Angeles: Green Integer Books, 2002.

Hoglund, Par. “Flip Book, Mid Sweden University 2007.” www.parhoglund.com. Web. 4 May 2012.

I Dance, I Dance Show. “Modern Dance Photos.” idanceidanceshow.blogspot.com. 24 September 2009. Web. 10 April 2012.

Mr. Dopestar. “Roni Horn at the Tate Modern, London, UK.” Art is Not Dead. 1 May 2009. www.artisnotdead.blogspot.com. Web. 4 May 2012.

Neukam, Judith. Threads Magazine. “Pleat School.” www.threadsmagazine.com. 28 May 2010. Web 8 May 2012.

Parsons Dance. “About.” www.parsonsdance.org. Web. 5 May 2012.

Perloff, Marjorie. Wittgenstein’s Ladder. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Rankine, Claudia and Juliana Spahr, Eds. American Women Poets in the 21st Century: Where Lyric Meets Language. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2002.

Spinelli, Claudia. “Roni Horn Interview.” Journal of Contemporary Art. June 1995. www.jca-online.com. Web. 2 May 2012.

Wolitzer, Meg. “On the Rules of Literary Fiction for Men and Women.” The New York Times Book Review, Second Shelf. March 30, 2012. Online.