The mind is assembling stuff all the time.

—Ralph Angel, from his essay Unhinged Articulation

A COLLAGE IS A COLLECTION OF ELEMENTS

My reading in and around poetry has transitioned toward the exploration of poems composed of fragments: writing that employs collage, whether seen or unseen, as an element in the poetic process.

What exactly is collage? As a visual artist, I sometimes take this word for granted. Not everyone is familiar with the term, and even Google wants to correct my spelling in an online search. Google prefers college to collage.

The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines collage as “an artistic composition made of various materials (as paper, cloth, or wood) glued on a surface” and “a creative work that resembles such a composition in incorporating various materials or elements.” Collage can also be used as a transitive verb.

THAT, IN COMPOSITION, FORM A NEW IMAGE.

In Composition as Explanation, Gertrude Stein defines composition as “... the thing seen by every one living in the living that they are doing, they are the composing of the composition that at the same time they are living is the composition of the time in which they are living.” Stein adds, “It is understood by this time that everything is the same except composition and time, and the time of the composition and the time in the composition.”

THE WORD COLLAGE COMES FROM THE FRENCH VERB COLLER, WHICH MEANS TO GLUE.

Origins of the word collage trace back to the Greek kolla—glue. The word collagen shares this Greek root—kolla (glue)—with gennao (I produce), referring to the intercellular fibrous proteins that hold a body together. Though the root of the word collage is glue, artists have expanded the definition to include other methods of fixing their materials to a surface: sewing or nailing, for example. In the Online Etymology Dictionary the first known use of the word collage is attributed to Wyndham Lewis, noting no specific source.

THIS ASSEMBLING OF FRAGMENTED MATERIALS—CUT-UP IMAGES, BITS OF TEXT, AND FOUND OBJECTS—AND GLUING THEM TO A FLAT SURFACE

Paper, perhaps the most commonly used material in collage, was invented in China during the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). In her book Collage, Assemblage, and the Found Object, Diane Waldman notes that some of the earliest documented examples of the practice of assembling and gluing paper fragments are found in twelfth century Japanese poetry.1 My search on this subject turned up images from the Ise shu: works by a woman known as Ise—also known as Ise no go (Lady Ise) and Ise no miyasudokoro (Consort Ise). Ise’s work—sometimes in the form of long poems—was recorded on scrolls as well as on byōbu: standing screens made from joined panels. In an image from the Ise shu, the text appears as a layer on a surface that has been prepared with torn fragments of colored paper, gold leaf, and ink.

The Paper Garden, written by Molly Peacock (published 2011), is the biography of Mary Delaney, an eighteenth century woman who, in her seventies, began creating a series of stunning, botanically accurate images of flowers. Delany completed well over a thousand of what she referred to as her ‘paper mosaicks’ composed entirely of bits of painted tissue paper, many of which are housed in the British Museum’s collection. Her collage Passiflora laurifolia: bay leaved, for example, blooms in over two hundred and thirty paper petals.

Other instances of assembling and pasting to a flat surface that come to mind include Victorian shellwork collages and butterfly wing collages, which incorporated a range of found materials not limited to paper. These were most often created by folk artists or amateurs, and not regarded as fine art or as having any influence on the art movements of their time. They are a nostalgic record of that moment in history.

WAS NOT GIVEN ATTENTION AS A MEDIUM IN A FINE ART MOVEMENT UNTIL THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY.

In Collage, Assemblage, and the Found Object, Diane Waldman begins by noting that, even though we find these predecessors of collage through several centuries, it was really not until the twentieth century that this medium was recognized as fine art, beginning in the Cubist movement, when Pablo Picasso glued a piece of cloth printed with a chair caning pattern to his canvas and called it Still-life with Chair-caning.2

Collage as a fine art form was further developed in the Dada and Surrealist movements, at which point artists used a variety of disparate materials—everyday objects and fragments of objects—in their compositions.

Waldman writes, “In the twentieth century the surface of a painting was transformed from a window into a flat plane. A new, clearly fictive image replaced the staged image of reality as it was known and accepted in art until then.” 3

FRAGMENTS WERE JUXTAPOSED TO CREATE NOT ONLY A NEW COMPOSITION, BUT A NEW NARRATIVE.

German artist Hannah Höch (1889 - 1978), one of the few women recognized for her contribution to the Dada movement, was a pioneer in the art of collage. Sometimes political statements, sometimes abstract compositions, her collages often combine graphic design and photo montage elements with needlework and dressmaking patterns. Höch continued creating collages throughout her career, as she said, “in an attempt to sublimate the aesthetic element into what for me are its ultimate possibilities.”4

Layers of paper suggest layers of meaning. In the collage composition, we as viewers see the individual components, the fragments. On one level, we recognize them for what they are—how they were used in their original context shows through.

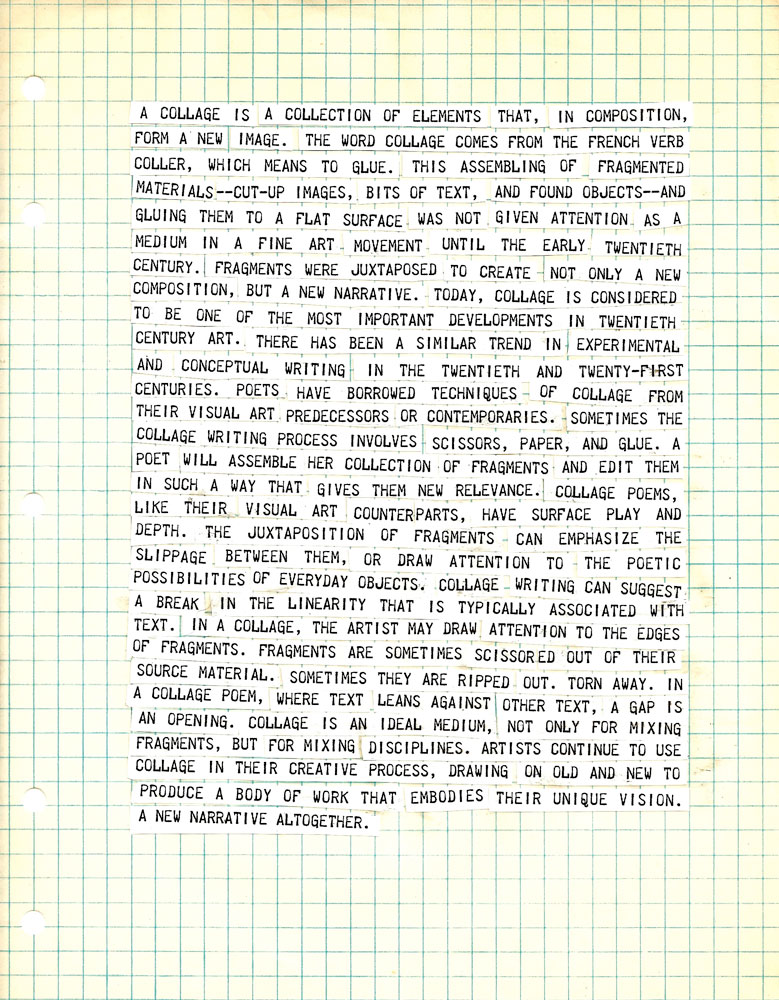

In the collage entitled Heads of State (1918-1920), Höch juxtaposes cutouts of two German politicians in their swimming trunks, paper cut into free-form shapes, and sheets of tissue paper printed with embroidery designs; flowers, butterfly, and a woman with a parasol are clearly visible behind a veil of cross stitch patterns (see fig. 1). We add another level of meaning when we associate these disparate elements: politics, paper, and stitching. How do they speak to me? How do they speak to each other? It’s possible that I will make different associations in my mind than the next viewer, or that I will make new associations each time I view it. The possibilities build, layer upon layer. The mind assembling and reassembling.

Fig. 1

TODAY, COLLAGE IS CONSIDERED TO BE ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT DEVELOPMENTS IN TWENTIETH CENTURY ART.

Twentieth century artist Robert Motherwell, whose collage work spans four decades, considered collage the most significant development in twentieth century art. In written material from the McClain Gallery exhibit Robert Motherwell: Four Decades of Collage (October 2013) Motherwell is quoted as saying that collage is a medium in which an artist “has the whole world and human history as subject matter, juxtaposition inconceivable before modern times.”

THERE HAS BEEN A SIMILAR TREND IN EXPERIMENTAL AND CONCEPTUAL WRITING IN THE TWENTIETH AND TWENTY-FIRST CENTURIES.

Tristan Tzara, avant-garde writer, performance artist, and author of the Dada Manifesto 1918, wrote these instructions for making a Dadaist poem:

Take a newspaper; take a pair of scissors. From the newspaper choose an article of the same length as you would like your poem to have. Cut out the article. Then carefully cut out every word of that article and put the words into a paper bag. Take out the slips of paper one by one and lay them out in sequence. Copy them just as they are. The poem will resemble you. And you will stand as a writer of unsurpassable originality and fascinating sensibility, though not understood by the general public.5

Tzara’s method focuses on the process of making a poem. It can be said that collage changed the nature of art—in any medium, whether it be visual art, writing, performance art, etc.—by expanding the range of what we consider to be art. This early twentieth century collage revolution, where emphasis was often placed on the process of making art rather than the end product, created an opening for experimental and conceptual artists. Waldman writes that collage “has stressed the meaning of process; it has brought the incongruous into meaningful congress with the ordinary and given the uneventful, the commonplace, the ordinary a magic of its own.”6

POETS HAVE BORROWED COLLAGE TECHNIQUES FROM THEIR VISUAL ART PREDECESSORS OR CONTEMPORARIES.

Recycled text, found poetry, and Flarf poetry are just a few of the forms of experimental or conceptual writing that make creative use of preexisting texts. Language is not something we own. It is something we share. We use the same alphabet and essentially the same vocabulary. Perhaps we even speak the same life-long sentence, but with our own, unique syntax. Why not embrace language for what it is: used. Why not recycle and repurpose text in our poems? John Cage wrote, “Poetry is having nothing to say and saying it: we possess nothing.”

SOMETIMES THE COLLAGE WRITING PROCESS INVOLVES SCISSORS, PAPER, AND GLUE.

One contemporary poet who describes her creative process as a collage method is Mei-mei Berssenbrugge. Her poems are often inspired by a collection of visual artifacts— Polaroids and other images—as well as fragments of text from her reading of science, philosophy, and art.7

In Two Conversations with Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, by Laura Hinton, Berssenbrugge says that her creative process has slowly evolved; now one of her poems might be made up of three hundred or so such fragments or elements. She discusses her creative process:

I find books that are contingent to my idea. I like French philosophy, Deleuze, Derrida. I like historic Buddhist texts—anything I read that strikes me as pertinent to my poem I underline. Then I print the notes and cut them out. I add pictures that seem to fit in some way, without questioning too deeply. Sometimes I take Polaroids. It’s an unconscious process. When I’m ready to write, I arrange these pieces of text, photos, notes across a big table and compose the poem. I used to appropriate texts directly. Now I alter them more.8

A POET WILL ASSEMBLE HER COLLECTION OF FRAGMENTS AND EDIT THEM IN SUCH A WAY THAT GIVES THEM NEW RELEVANCE.

Now she alters them more. I see this is as the key point of departure. This is where the process of collage moves from the simple gluing down of a sentimental collection of objects to a viable form of artistic expression, the stage in which fragments combine in such a way that allows for an opening: a perspective that shapes new levels of meaning.

Berssenbrugge expands on this notion of poem as collage, saying that she uses visual images “like patches of concrete experience” in her poems, then collages her collection of images together, combined with “abstractions or ideas.”9

This juxtaposition of concrete and abstract is evident, for example, in part one of Berssenbrugge’s poem entitled I Love Morning, from the collection Nest:

We’re in New Mexico.

It’s summer—all morning to lounge in bed, talk on the phone, read the paper.

Martha pats her spiky, old cat, Manet, studies cat’s cradle from a book.

Time is ethos, as if we’re engendered by our manner in it, not required to be in ourselves.

With no cause to act on time, there’s no pointing beyond, so he gets up and plays Scarlatti in his underwear.

Being together, like scrim, defocuses space.

Knowability (features) of her face, continually passing into expression, is detached from her, a para-existence beside mother, halo, unraveling.

Light increases toward the red spectrum of day. She nurses her cat with a syringe supported against my large arm.

My body is a film on her preconscious of images she chooses to line conversation.

Its alterity becomes a nuance of our ineluctable situation of futons, dishes, books, with the potential of a destabilized surface of time, no outflow through pink walls.

Atmospheric presence soaks objects.10

We can clearly make out what Berssenbrugge refers to as the concrete visual components in this poem, the everyday objects that she has assembled, then arranged in her composition: bed, phone, paper, cat, book, underwear, mother, futon, dishes, walls. These objects are soaked in atmospheric presence: those abstractions and ideas carefully scissored out of texts, then glued into the arrangement. Words like alterity (a philosophical term meaning otherness, referring to a state of being), ethos, preconscious, and knowability suggest references to Berssenbrugge’s reading in philosophy, psychology, and logic. Light, spectrum, scrim, space: I imagine these terms referring to her reading on art, color theory, or even Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Color.

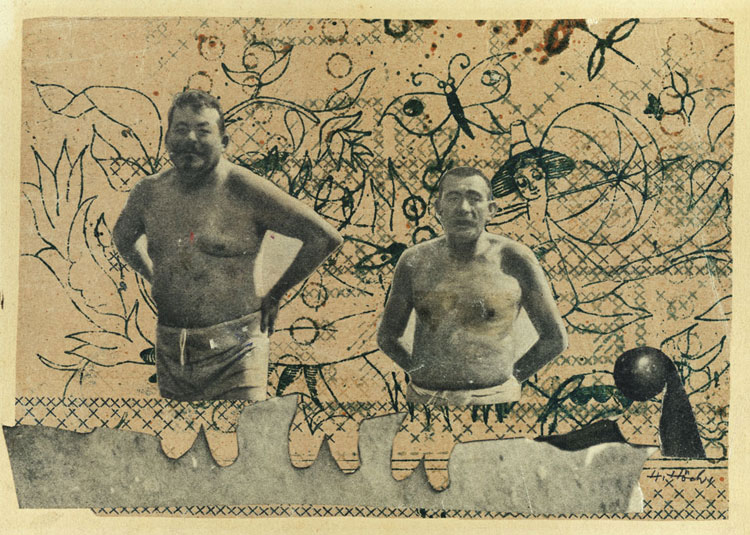

Fig. 2

This juxtaposition of concrete and atmospheric once again brings to mind the collages of Hannah Höch—her photomontages, in particular. Take, for example, Around a Red Mouth (1967) (see fig. 2). Even before reading the title, the glossy, red lips are clear and concrete. I can also make out the ruffle of a petticoat, and the cross-sections of crystals. Beyond that, Höch’s composition is soaked in an ocean of atmospheric color and movement: fluid waves of pinkness.

In this collage, Höch has combined elements and fragments that are arranged in a somewhat ambiguous composition. One object flows into the next in an almost seamless way. I imagine if I ran my hand across the surface of this collage, I would likely be able to detect the cleanly cut edges of paper. But viewing it from a slight distance (or in my case, viewing a digital reproduction of the original) the seams that connect the images of fabric are not evident. A pink ruffle flows smoothly into a wave of a geode in cross-section, also tinted in blushing pink. Overall, I see the image as a comment on gender and femininity. One viewer might interpret it differently than the next. There is a subtle tension between knowing and questioning. I feel this tension in Berssenbrugge’s poem, too.

COLLAGE POEMS, LIKE THEIR VISUAL ART COUNTERPARTS, HAVE SURFACE PLAY AND DEPTH.

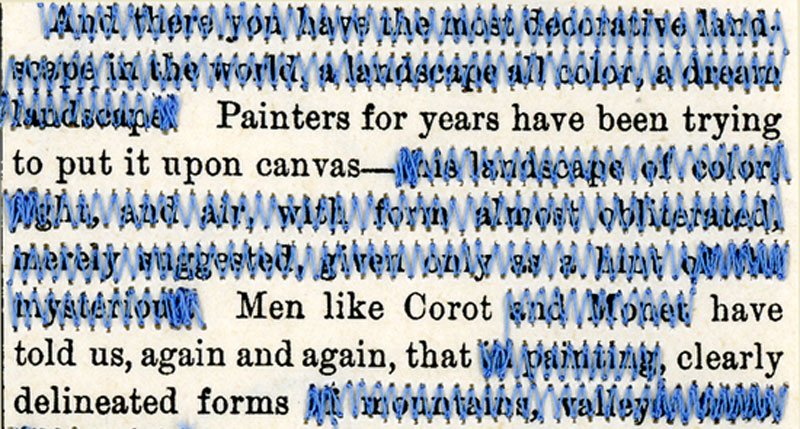

In her essay Collage and Poetry, Marjorie Perloff writes that collage in visual art typically combines an assortment of everyday items—scraps of newspaper, images torn out of magazines and books, maps, subway tickets, food wrappers, keys, nails—with lines and shapes that are drawn or painted, to create a composition that becomes a “curiously contradictory pictorial surface.” She adds that it also “subverts all conventional figure-ground relationships, it generally being unclear whether item A is on top of item B or behind it or whether the two coexist in the shallow space which is the picture.”11

Berssenbrugge refers to how, once her hundreds of textual and visual fragments have been assembled, she “smoothes out the grammar.”12 I think there is also a certain smoothing out of time and space. In an artist statement that Berssenbrugge contributed as part of the In Their Own Words feature at the Poetry Foundation’s website, she says, “I try to write as if time were simultaneous and consecutive at once and even simultaneous with the future ... I think of our sense of passing time or consecution as a perceptual device perhaps like depth perception.”

Berssenbrugge describes a certain resonance in her narrative that goes “beyond three- dimensional space,” creating something she calls “a linguistic surface.”13

I draw a parallel between Berssenbrugge’s linguistic surface and Perloff’s notion of figure-ground relationships. My mind links smoothing out the grammar with coexisting in the shallow space. Smooth and shallow. Time and space, figure-ground. Item A on top of item B. The materials glued on a surface engage in surface play. They have depth that goes beyond three-dimensional.

THE JUXTAPOSITION OF FRAGMENTS CAN EMPHASIZE THE SLIPPAGE BETWEEN THEM, OR DRAW ATTENTION TO THE POETIC POSSIBILITIES OF EVERYDAY OBJECTS.

The collage approach to writing poetry is often categorized as experimental, sometimes even conceptual writing, depending on the process. In a conversation with Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Laura Hinton notes that Rae Armentrout argued against a point made by the mainstream of modern writers (mostly men) that “women writers are less experimental and more traditional by nature.” In her essay Feminist Poetics and the Meaning of Clarity, Armentrout described women as “actually very attracted to an experimental kind of writing that rebukes this set of conventions.” Berssenbrugge agrees, saying that “as outsiders” women have more freedom to experiment.14

Motherhood, femininity, domesticity, and family are motifs that repeat throughout Nest. The title itself suggests a kind of domestic space, in nature. But the poems do not confine us to the material or sentimental domestic space of a house. They do not box us in; they expand into a broader space, a network of philosophical and scientific spheres, as in this excerpt from part five of her poem Permanent Home:

Give a house the form of an event.

Relate it to something there, a form of compassion.

Your point of view is: it’s solid already, so there’s warmth.

In this primitive situation, pure form translates that former empire of space as wilderness.

Chinese space breaks free from the view in front of me, while my house continues rotating on earth. 15

In her conversation with Hinton, Berssensbrugge adds that even though collage writing is considered experimental, it is actually perhaps a more natural method of writing. Women, especially mothers, tend to make art in a fragmented way: in short creative bursts throughout the day or week, as their schedules and energy allows.

Berssenbrugge also suggests that it is more naturalistic to “portray fragments” in a narrative. She says to Hinton, “If we sit here, for example, and people walk by, talking, and you record what we say and they say in patches, that’s actually more representational than a single narrative line.”16

Recorded in patches. I think of quilts: a collection of fabric scraps, cut further into fragments, using scissors. Pieced together, exploring relationships between fabric colors, patterns, and textures. Quilts are typically constructed one block at a time, the blocks assembled into a whole. A finished quilt is draped over a bed, over a body. It is something heavy or light. A layer of collaged patches, a quilt moves with or against what lies beneath it.

In her poetry collection, Trimmings, Harryette Mullen has assembled prose poems. In an interview with Barbara Henning, Mullen compares this collection to a quilt made by her grandmother, in a cathedral window pattern. This traditional design is pieced entirely by hand—the individual squares, though tedious to construct, are quite portable.

Trimmings... allowed me to make a kind of long poem composed of discreet units, so that in effect, I could write brief manageable poems that were parts of a longer work that was the book-length poem. The discreet units, stanzas or paragraphs, form various patterns like the pieces of a quilt. I could start anywhere, proceed in no particular order, writing whenever I had the chance and the energy... I could continually end and begin, without feeling the trauma of endings, the fear and uncertainty of beginnings. My own consolation in the face of rupture, a writing through the gaps and silences.

Mullen credits Gertrude Stein as a primary source of inspiration for Trimmings. In her collection of essays, The Cracks Between What We Are and What We Are Supposed to Be, Mullen writes, “Tender Buttons remains an extraordinary source of creative energy for my poetry and me. Two of my books, Trimmings and S*PeRM**K*T, began as responses to Tender Buttons.”17

In a conversation with Cynthia Hogue, Mullen speaks further on the subject of Tender Buttons:

I was analyzing what Stein was doing to figure out what I could use and I found that on a lot of levels, I could use what she was doing: the structure of the book itself, in terms of using a prose-poetry form, and a paratactic sentence that is compressed, that is not really a grammatical sentence but that makes sense in an agrammatical way, in a poetic way. Also, in her use of subject matter, where she is dealing with objects, rooms, and food, the domestic space that is a woman’s space ...18

Mullen categorizes Trimmings as a long poem composed of prose poems. She also refers to these prose poems as list poems. In her conversation with Henning, Mullen describes her process—in the making of Trimmings, in particular:

First, I made a list of words referring to anything worn by women. Each word on that list became the topic of a prose poem (I started with clothing, then decided to include accessories. There were a few things I decided not to write about, such as wigs, dentures, and so forth.) Then I made more lists by free associating from words on the first list. I generated lists of words that might be synonyms (pants/jeans/slacks/britches), homonyms (duds/duds, skirt/skirt), puns or homophones (furbelow, suede/swayed), or that had some metaphorical, metonymical, or rhyming connection (blouse/dart/sleeve/heart, pearl/mother, flapper/shimmy/chemise), or words that were on the same page of the dictionary (chemise/chemist). I would improvise a possible sequence of words, seeing what the lists might suggest in the way of a minimal narrative, a metaphor, an association, or pun.

I would categorize these prose poems not only as list poems, but as collage poems, as well. Mullen’s lists are, as in a collage, a collection of everyday objects assembled on a surface. She writes, “My poems often recycle familiar and humble materials in search of the poetry found in everyday language.”19 Belts, petticoats, bodices, stockings, garters, corsets, and lace are among the familiar materials included in the lists of Trimmings. Mullen has neatly scissored out an assortment of women’s adornments from Stein’s Tender Buttons, then pieced them together in combination with her own list of objects. Take, for instance, Stein’s A Petticoat:

A light white, a disgrace, an ink spot, a rosy charm.

Mullen cut Stein’s petticoat further into fragments. Then she reassembled them, expanding the language by adding her own trimmings:

A light white disgraceful sugar looks pink, wears an air, pale compared to shadows standing by. To plump recliner, naked truth lies. Behind her shadow wears her color arms full of flowers. A rosy charm is pink. And she is ink. The mistress wears no petticoat or leaves. The other in shadow, a large, pink dress.20

Mullen uses women’s clothing and accessories as the symbol of woman. Fabric is cloth which becomes clothing, but fabric also suggests the body under the clothes. She notes that her poems employ a metonymical description of a woman in terms of what she’s wearing, for example, skirt commonly refers to a woman as well as to an article of clothing that women wear.

There are layers of meaning collaged into Trimmings. The title Mullen chose for her collection—Trimmings—suggests two definitions that are opposites: decoration (as in the lace trimming added to a bodice) and parts that are cut away and discarded (the clippings, the scraps, the waste). Throughout the collection, you’ll find these opposites, juxtaposed:

Decorative scrap. A rib, on loan. Fine fabric, finished at edges. Fit for tying or trimming. Narrow band, satin, a velvet strip. A ribbon wound around her waist. A glancing bow. Red ribbon woven through her, blue-ribbon blonde. For valor, a shred of dignity. A distress torn to ribbons.21

COLLAGE WRITING CAN SUGGEST A BREAK IN THE LINEARITY THAT IS TYPICALLY ASSOCIATED WITH TEXT.

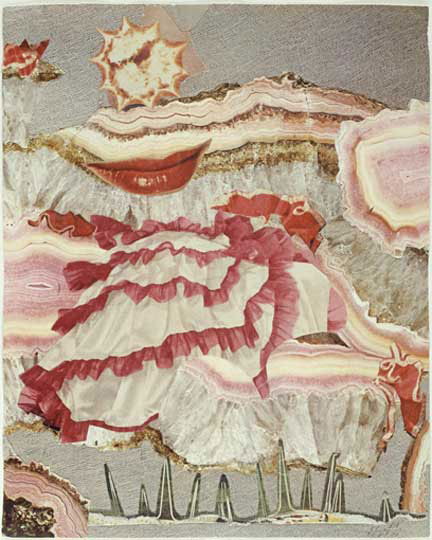

Mullen drew her inspiration, as she notes, from Stein—in particular, Stein’s paratactic writing style. When I think of parataxis—the juxtaposition of distinctly dissimilar images or fragments, without a clear connection—I see a collage. The description has a very visual connotation. And if I see a poem by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge as a photo montage by Hannah Höch, then I see Trimmings as a series of collages similar to Höch’s Tailor’s Flower (Schneider Blume, 1920). In this piece, Höch uses what appears to be segments of cut-out lines and shapes from instructional diagrams (possibly for needlework) glued down in sharp angles on graph paper, in an abstract composition (see fig. 3). Where Berssenbrugge “smoothes over” fragments of text and lays them down on the page in long lines, Mullen favors abrupt edges and breaks in linearity, on an underlying prose grid.

Fig. 3

IN A COLLAGE, THE ARTIST MAY DRAW ATTENTION TO THE EDGES OF FRAGMENTS.

In her artist statement/essay entitled Thinking of Follows, poet Rosmarie Waldrop refers to collage as “The Splice of Life.” She writes: “Collage, like fragmentation, allows you to frustrate the expectation of continuity, of step-by-step-linearity. And if the fields you juxtapose are different enough there are sparks from the edges.”

Early on in her writing of poetry, Waldrop experimented with collage. Essentially, she used Tristan Tzara’s method for making a Dadaist poem:

I turned to collage early, to get away from writing poems about my overwhelming mother. I felt I needed to do something “objective” that would get me out of myself. I took books off the shelf, selected maybe one word from every page or a phrase every tenth page, and tried to work these into structures. Some worked, some didn’t. But when I looked at them a while later: they were still about my mother.22

The poem will resemble you. What the mind has assembled—subconsciously and at any given time—will surface in your poems. Waldrop’s revelation in this exercise was that having no real control over the subconscious mind is not a limitation. That moment of acceptance—knowing you have no control—is actually freeing. This allows an artist to focus, consciously, on form. “For the rest,” Waldrop writes in her artist statement, “all you can do is try to keep your mind alive, your curiosity and ability to see.” Her second revelation was “that any constraint stretches the imagination, pulls you into semantic fields different from the one you started with.” She adds that even though her poems were still about her mother, “something else was also beginning to happen.”23

Like Berssenbrugge and Mullen, Waldrop takes fragments from existing texts and reinvents them in new constructions. In her collection of prose poems, Lawn of Excluded Middle (part two of the trilogy Curves to the Apple), Waldrop begins with phrases borrowed from this passage in Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations:

422. What am I believing in when I believe that men have souls? What am I believing in, when I believe that this substance contains two carbon rings? In both cases there is a picture in the foreground, but the sense lies far in the background; that is, the application of the picture is not easy to survey.24

Waldrop’s poem:

When I say I believe that women have a soul and that its substance contains two carbon rings the picture in the foreground makes it difficult to find its application back where the corridors get lost in ritual sacrifice and hidden bleeding. But the four points of the compass are equal on the lawn of the excluded middle where full maturity of meaning takes time the way you eat fish, morsel by morsel, off the bone. Something that can be held in the mouth, deeply, like darkness by someone blind or the empty space I place at the center of each poem to allow penetration.25

Is it any wonder that, like many poets, Waldrop draws inspiration from Wittgenstein? His writing reads like poetry. Many of his philosophical propositions address the nature of language and its inadequacies. Reading through Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, I’ve found propositions that seem to relate directly to poetry. Number 499, for example, parallels the sort of strangeness that a reader must navigate in order to find their way into a poem.

499. To say “This combination of words makes no sense” excludes it from the sphere of language and thereby bounds the domain of language. But when one draws a boundary it may be for various kinds of reason. If I surrounded an area with a fence or a line or otherwise, the purpose may be to prevent someone from getting in or out; but it may also be part of a game and the players be supposed, say, to jump over the boundary, or it may shew where the property of one map ends and that of another begins, and so on. So if I draw a boundary line that is not yet to say what I am drawing it for.

I apply Wittgenstein’s phrase, “This combination of words makes no sense,” to a collage poem. A collage of fragments could be seen as making no sense, but once the reader has jumped over the boundary of language, the possibilities of meaning in that composition become endless. One map ends and that of another begins.

Berssenbrugge and Mullen appropriate found text in their poems without making direct reference to their sources (except perhaps in interviews or articles in which they discuss their creative process). Waldrop, too, uses unidentified fragments of text. In an interview with Matthew Cooperman, Waldrop explains that what she does is not “citational.” She continues, “In a citation, as I would define it, you want to bring the author and his/her authority into your text along with the citation.” Waldrop states that she uses fragments to add texture to her writing, much in the same way that Pablo Picasso might have glued a scrap of newspaper to a painting, or Robert Rauschenberg might have incorporated a torn bit of a reproduction of an historical work of art into his own collage.26 Waldman does, however, indirectly credit Wittgenstein in her notes at the end of the collection, Lawn of Excluded Middle. She writes, in item number 7: “Wittgenstein makes language with its ambiguities the ground of philosophy. His games are played on the lawn of excluded middle.” British astrophysicist A.S. Eddington and (Sir Isaac) Newton receive mentions in numbers 8 and 9, respectively.27 In doing so, Waldrop acknowledges a sort of layering in her collage writing— a palimpsest. I am reminded here of Robert Motherwell’s comment that the medium of collage offers an artist “the whole world and human history as subject matter.” In her artist statement, Waldrop writes, “The blank page is not blank. Words are always secondhand... No text has one single author. Whether we are conscious of it or not, we always write on top of a palimpsest.” She adds that many poets have “fore-grounded this awareness as technique, using, collaging, transforming, ‘translating’ parts of other works.”

In Thinking Poetry: Readings in Contemporary Women’s Exploratory Poetics, Lynn Keller notes that, in addition to Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, another text that serves as one of Waldrop’s primary palimpsestic resources in Lawn of Excluded Middle is Eddington’s The Nature of the Physical World (1929); Robert Musil’s novella The Perfecting of a Love (1911), she writes, provides an elusive “kind of ghost plot as well as some of the imagery, atmosphere, and thematic preoccupations.”28

Waldrop explains that this collection’s title is a play on the law of the excluded middle in logic, one of the three classic laws of thought. It states that for any proposition, either that proposition is true, or the negation is true. For example, this proposition: this is paper. The law of the excluded middle supports that either this is paper or it is not the case that this is paper. The middle ground—that this is neither paper nor not-paper—is excluded from the possibilities, as defined by logic.

Law is cultivated into lawn. Waldrop’s poems are an exploration of what she perceives in that middle ground: the fertile space between what is true and and what is false. Furthermore, this collection centers on “the idea of woman as the excluded middle,” and— going deeper into that center—what lies at the middle of a woman’s body: the womb.29

In her introduction to Curves to the Apple, Waldrop states that she has chosen to write prose poems because this form, for her, “has come to fit Pound’s postulate of ‘a center around which, not a box within which.’”30 This brings to mind what Diane Waldman wrote about twentieth century painting moving from a staged, window view to an abstract or fictive image. Waldrop’s series of prose poems, rather than being windows, are collages that explore the possibilities outside of the frame—all that has been excluded from the window view— around the margins of reality and logic, between what is and what is not.

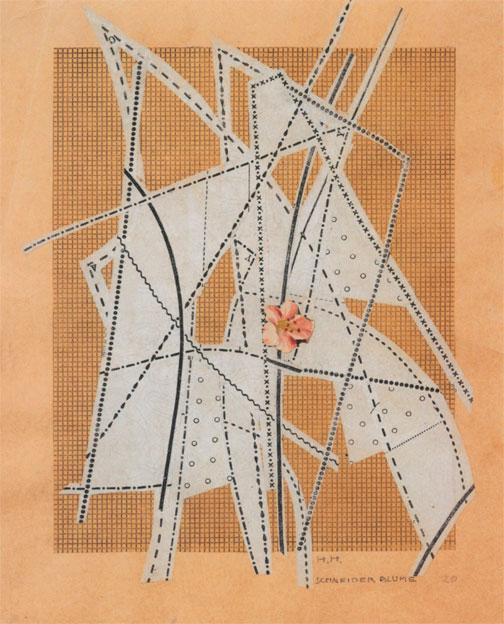

Fig. 4

FRAGMENTS ARE SOMETIMES SCISSORED OUT OF THEIR SOURCE MATERIAL. SOMETIMES THEY ARE RIPPED OUT. TORN AWAY.

If I were to pair Rosmarie Waldrop’s poems in Lawn of Excluded Middle to a visual art counterpart, I would naturally curve back to the collages of Robert Motherwell—his appreciation of palimpsest and working with that foundation of materials already established by human history. In his collage View from a High Tower (1944-1945), Motherwell has applied torn canvas, maps, and layers of tissue-like paper to the surface (see fig. 4). Semi-transparent layers of paint have been applied over lined paper. Paint that looks as though it has been scraped in certain areas. I notice, in particular, his treatment of the edges of these fragments. There are ripples and creases. Hints of shadows where the fragments touch, glued —though not seamlessly—together. There are intentional gaps between fragments where the artist, having gone back into the composition once everything had been glued into place, tore certain pieces of fragments away. “What’s left over if I subtract the fact that my leg goes up from the fact that I raise it?”31

I associate these irregular edges and surfaces with Waldrop’s prose poems. Unlike Berssenbrugge’s grammar—smoothed out on the page—Waldrop’s grammar seems to leap from one object or fragment to another. Where Berssenbrugge’s sentences appear as elongated strands, Waldrop’s are a strange and exciting mash-up. I imagine her going back into these sentences and tearing away a little bit more, here and there, like Motherwell. Intentionally widening those leaps and gaps.

In number fifteen (part one of Lawn of Excluded Middle) bodies leap from desire to skyline to underfoot. Stomach, throat, crash, water:

The word “not” seems like a poor expedient to designate all that escapes my understanding like the extra space between us when I press my body against yours, perhaps the distance of desire, which we carry like a skyline and which never allows us to be where we are, as if past and future had their place whereas the present dips and disappears under your feet, so suddenly your stomach is squeezed up into your throat as the plane crashes. This is why some try to stretch their shad- ow across the gap as future fame while the rest of us take up residence in the falling away of land, even though our nature is closer to water.32

IN A COLLAGE POEM, WHERE TEXT LEANS AGAINST OTHER TEXT, A GAP IS AN OPENING.

Waldrop writes, “I worried about the gap between expression and intent, afraid the/ world might see a fluorescent advertisement where I meant to show a/ face.” She continues, “Far better to cultivate the gap itself.”33 Waldrop refers to this concept that she calls gap gardening throughout her poems. “Understanding, too, enters more easily through a gap between than where a line is closed upon itself.”34

In Susan Howe’s collection of poems That This, gaps expand. White space—the blank page—acts as a sort of fragment in and of itself: a fracture, a pause, a space in which to meditate. Breathing room. In the first prose entry of this collection, Howe writes, “Starting from nothing with nothing when everything else has been said...”35 She states, in an interview conducted by Lynn Keller, “I would say that the most beautiful thing of all is a page before the word interrupts it.”36 The blank page has infinite possibilities: “there is no up or down, backwards or forwards,” Howe says. “You impose a direction by beginning.”37

In That This, it is evident that the words on the page are not Howe’s only concern. There is, clearly, just as much emphasis placed on the white space around them, as well as their placement within that openness. Howe credits Agnes Martin, whose paintings are “spare and infinitely suggestive at the same time,” as an inspiration for her poems.38

COLLAGE IS AN IDEAL MEDIUM, NOT ONLY FOR MIXING FRAGMENTS, BUT FOR MIXING ARTISTIC DISCIPLINES.

The cover of That This celebrates the beauty of the blank page. It is pure white, briefly interrupted by the poet’s name and the book’s title, set in serif type and printed in black ink. Below that, and centered on the cover, there is the image of a small swatch of Prussian blue fabric. It looks like fine silk damask. The rectangle has been cut out with scissors, and its raw edges have begun to fray. The coupling of text and textile—this blue swatch juxtaposed with the white paper—and That leaning against This hints at the collage to be found inside the book.

We learn, reading the first part of this collection, The Disappearance Approach, that this blue fabric fragment is all that’s left of the wedding dress worn by a woman named Sarah Edwards, in the eighteenth century. Throughout the book, but most apparently in the first section, Howe appropriates fragments from the Edwards family papers found in a folder in the Beinecke Library archives. In particular, Howe credits the “private writings” of Hannah Edwards Wetmore as a source for her collaged fragments.39

In this section, Howe juxtaposes fragments from the Edwards papers with her own prose, written about and around her husband’s sudden death in 2008. Part two of this book, Frolic Architecture, is made up of poems composed in an innovative and curious mix of textual and visual collage. Is this poetry or is it visual art? Or both?

On one hand, this abrupt shift to mixed media is surprising. On the other hand, not so surprising, given that Howe worked as a visual artist for many years prior to writing poetry. Writing, she says, was something that evolved in her work by accident—it was, however, a natural extension of her work in the visual arts, where she often incorporated found and original text in her artwork. This progressed, eventually, to the point where Howe was essentially arranging words on walls. Her friend, the poet Ted Greenwald observed, “You have a book on a wall, why don’t you just put it into a book?”40

Like Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Howe uses scissors, but she takes her cutting and pasting to another level. On the first page of Frolic Architecture, she begins:

That this book is a history of

a shadow that is a shadow

of me mystically one in another

Another another to subserve41

This is the only poem in part two that is printed on the page, unaltered. From here on, Howe’s poems involved a process that included cutting, arranging, and pasting text. Then making several copies of this arrangement with a Xerox machine. Then cutting and arranging these copies, everything held together with clear, invisible tape. This process repeated until she had it right. “The getting it right has to do with how it’s structured on the page as well as how it sounds—this is the meaning,” Howe explains.42

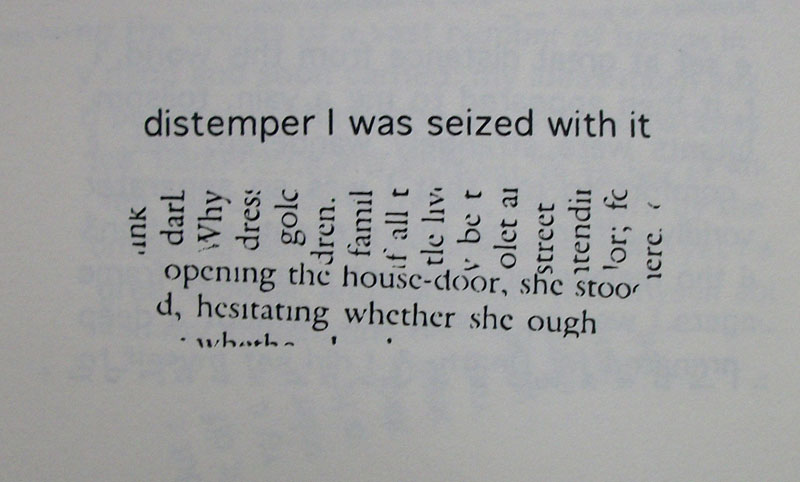

The first several poems in this section float near the center of the page, as in page 55 (see detail, fig 5), where the line “distemper I was seized with it” hovers above two fragments that are less legible—the text of one running perpendicular to the other—and together, resemble a sort of shadow cast by the clear voice suspended above it.

Fig. 5

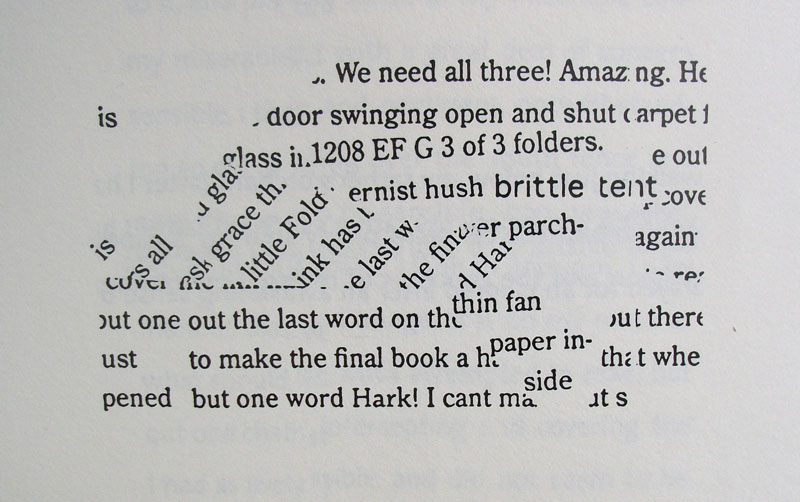

This is one example of where the appropriated eighteenth century text, even in a tiny fragment of the original fragment, is particularly evident. Other instances include page 51 (see detail, fig. 6) where we read, “but one word Hark!” Hark—one word—suggests antiquity and palimpsest, a “history of a shadow.” Also woven into the structure of this poem are hints pointing to the locations in which Howe discovered her historical fragments: “1208 EF G 3 of 3 folders.” On page 49 we read, “Box 24. Folder 1377.”

Fig. 6

The blocks of text collage in Frolic Architecture begin to shape-shift and drift from the center of the page. Page 58 is a soft mound of text. Page 60 is blank: all of its text appears to have spilled onto page 61, everything crowded at the far edge. The poems on page 72 and 73 are set deep along the center seam of the book, almost mirroring each other.

In this section of That This, Howe’s work bridges poetry and visual art. At the same time, I think it enacts a kind of rupture in language. Though we recognize hints and traces of straight lines created by typewriter or letterpress printing, Howe’s collages combine fragments in such a way that deviates from the linearity that we would normally associate with text. Howe’s interrupted fragments, arranged at angles and crossing over each other, seem to emphasize that which is unsayable or unspoken. They expand into visual interpretation. She describes her process in the creation of these poems as being very much like making visual art. Howe writes at a drawing table, where she is able to “scumble lines together and turn the paper sideways or upside down.”43

That verb—scumble—is associated with painting and drawing. To scumble means to modify lines and patches of color by applying semi-opaque layers (typically with a dry brush) or by rubbing. Howe says, “For me a poem doesn’t exist until I see it (these days in Times Roman font) on paper ... I like to lay the pages out on the table so one speaks to and almost mirrors the other. I finish one and answer it with the next.”44

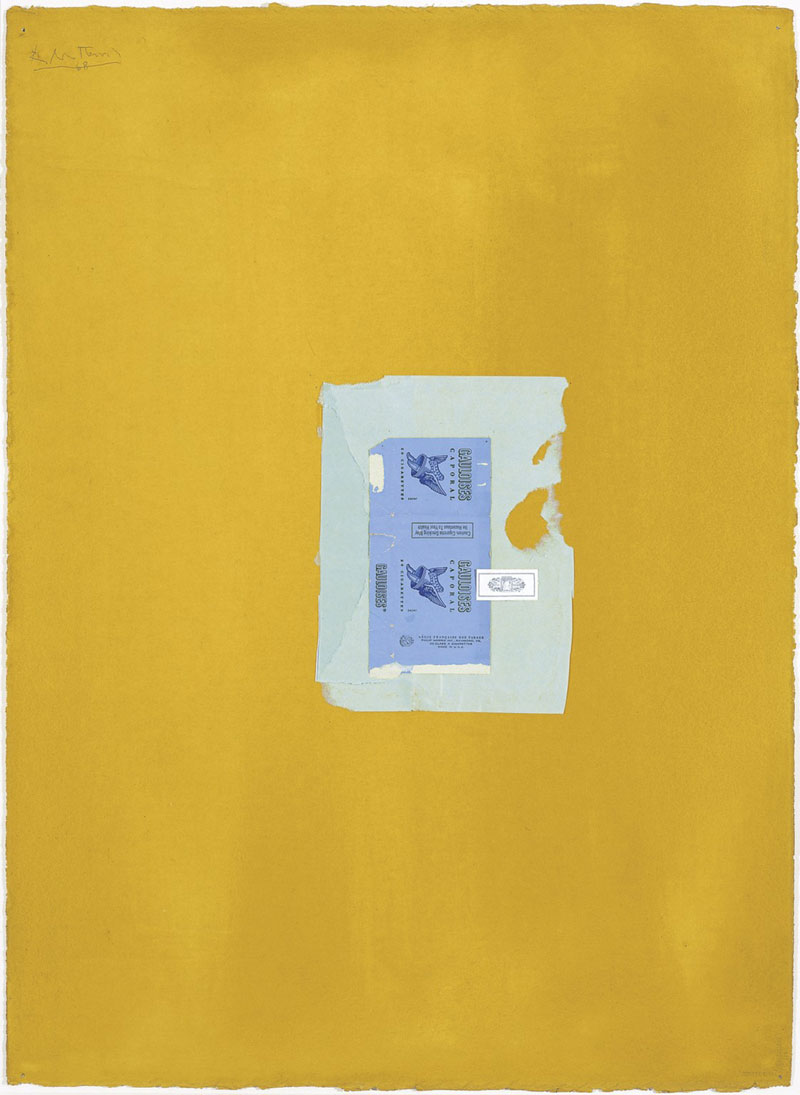

Fig. 7

For the sake of continuity, I’ll pair Howe’s poems with a visual collage by Robert Motherwell: In Yellow Ochre with Two Blues (1968). Here, a blue fragment—an iconic French Gauloises cigarette wrapper—interrupts the beauty of the yellow ground (see fig. 7). Our focus shifts back and forth, between fragments and ground, that and this. Or am I pairing Motherwell’s collage with a poem? It’s almost as if Motherwell has enacted a prose poem: a block of text positioned in the center of the page.

ARTISTS CONTINUE TO USE COLLAGE IN THEIR CREATIVE PROCESS, DRAWING ON OLD AND NEW TO PRODUCE A BODY OF WORK THAT EMBODIES THEIR UNIQUE VISION.

I’ve addressed the use of text fragments in the additive process—in other words, the assembling of fragments and building up of layers in the composition. There are also those poets whose work with fragments is a subtractive process, as in the form of erasure poems.

In The Desert, Jen Bervin has composed a poem using a copy of John Van Dyke’s book, The Desert: Further Studies in Natural Appearances (1901) and a sewing machine.

Fig. 8

The Desert was produced in a limited edition of forty copies, employing thousands of yards of pale blue thread. Bervin engaged in her process of poem-making by sewing across the pages of Van Dyke’s text—one hundred and thirty pages in all. With her machine set to zigzag, the poem revealed itself, line by line (see detail, fig. 8). Bervin writes, “I used atmospheric fields of pale blue zigzag stitching to construct a poem ‘narrated by the air’— ‘so clear that one can see the breaks.’’45

Mary Ruefle’s erasure poems are often both subtractive and additive, combining erasure and visual collage. To date, only one of these erasure poems has been reproduced: A Little White Shadow (2006). The others remain as one-of-a-kind treasures.

Fig. 9

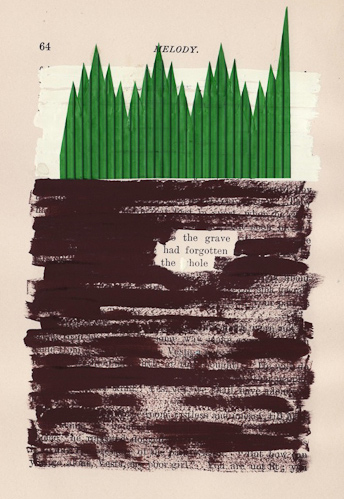

With the pages of vintage books as her writing surface, Ruefle reveals her new text using white correction fluid, ink, paint, and an assortment of paper artifacts. On page 64 of her poem Melody, for example, (see fig. 9) Ruefle incorporates a fragment of vibrant green that we recognize as a familiar sushi garnish.

One could argue that every poem ever made is, on some level, a collage. The human brain is constantly assembling objects, landscapes, colors, dreams, music...trimmings. While composing a poem, the poet’s mind works to juxtapose these artifacts that may be disparate in nature: paper, cat, syringe. The mind is in a constant state of oscillation, shaping new levels of meaning as a narrative or lyric unfolds. So much of this brain activity happens on a subconscious level. Who fully understands the brain’s role in the creative process?

In this exploration of experimental poetry, I’ve chosen to focus specifically on collage as a conscious choice in the writing process. Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Harryette Mullen, Rosmarie Waldrop, and Susan Howe are all poets who acknowledge the use of borrowed or recycled text in their poems. These four women represent a sample of contemporary poets whose writing process involves the manipulation of fragments taken from pre-existing texts.

I’ve presented their work in order of what I consider smoothest to most-fragmented collage writing. Berssenbrugge’s lines, composed of conventionally structured sentences, are smooth strands that stretch from margin to margin. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Howe’s sentence fragments not only break the linearity we typically associate with writing and reading poetry, they move and begin to migrate off of the page entirely.

A NEW NARRATIVE ALTOGETHER.

Why am I drawn to collage poems? Is it because the divergent writing practices of these poets push the boundaries of what most readers expect from poetry? Or because creating a series of poems in this fragmented way feels natural to me in my own work? Yes and yes. I appreciate collage writing because its origins are rooted in visual art; not only does it parallel the collage practice as it was developed in visual art, it also allows for the ideal opening or connection between a variety of artistic disciplines. But more fundamentally I am inspired by the process. I feel a deep connection in the making of these poems—cutting and assembling and gluing, whether seen or unseen. I am interested in how each of these poets approaches the blank page (or the palimpsest) and the profound and individualistic ways in which they limn language on that surface, creating innovative juxtapositions of words and textual dimension in their poetry.

NOTES

1Waldman, Diane, Collage, Assemblage, and the Found Object (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 8.

Return to Reference.

2Ibid., 8

Return to Reference.

3Ibid., 11

Return to Reference.

4Lavin, Maud, and Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife: The Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Höch (New Haven: Yale UP, 1993), appendix 213.

Return to Reference.

5Wescher, Herta, Collage (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1968), 134.

Return to Reference.

6Waldman, Diane, Collage, Assemblage, and the Found Object (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 15.

Return to Reference.

7Frost, Elisabeth A., and Cynthia Hogue, Innovative Women Poets: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry and Interviews (Iowa City: U of Iowa, 2006), 44.

Return to Reference.

8Ibid., 54.

Return to Reference.

9Klein, Michele G., BOMB—Arts in Conversation (BOMB Magazine, Summer 2006,

Web. 12 July 2014).

Return to Reference.

10Berssenbrugge, Mei-mei, Nest (Berkeley, CA: Kelsey St., 2003), 39.

Return to Reference.

11Perloff, Marjorie, “Collage and Poetry” (Marjorie Perloff RSS. N.p., 1998, Web. 7 Aug. 2014).

Return to Reference.

12Hinton, Laura, “In the Margin, Fertile Things Happen: Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge in Conversation” (Poets.org. Academy of American Poets, 2006. Web. June-July 2014)

Return to Reference.

13Frost, Elisabeth A., and Cynthia Hogue, Innovative Women Poets: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry and Interviews (Iowa City: U of Iowa, 2006), 53.

Return to Reference.

14Waldrop, Rosmarie. “Thinking of Follows.” Electronic Poetry Center. Buffalo.edu, 24 Apr. 2000. Web. 18 July 2014, 48-49.

Return to Reference.

15Berssenbrugge, Mei-Mei, Nest (Berkeley, CA: Kelsey St., 2003), 15.

Return to Reference.

16Frost, Elisabeth A., and Cynthia Hogue, Innovative Women Poets: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry and Interviews (Iowa City: U of Iowa, 2006), 49.

Return to Reference.

17Mullen, Harryette Romell, The Cracks between What We Are and What We Are Supposed to Be: Essays and Interviews (Tuscaloosa: U Alabama, 2012), 26.

Return to Reference.

18Hogue, Cynthia, and Harryette Romell Mullen, “Interview with Harryette Mullen,” (Postmodern Culture 9.2 (1999) Project MUSE, Web. 4 Aug. 2014)

Return to Reference.

19Rankine, Claudia, and Juliana Spahr, American Women Poets in the 21st Century: Where Lyric Meets Language (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 2002), 406.

Return to Reference.

20Mullen, Harryette Romell, Recyclopedia (St. Paul, MN: Graywolf, 2006), 11.

Return to Reference.

21Ibid., 51.

Return to Reference.

22Waldrop, Rosmarie, “Thinking of Follows,” (Electronic Poetry Center. Buffalo.edu, 24 Apr. 2000, Web. 18 July 2014).

Return to Reference.

23Ibid.

Return to Reference.

24Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations, (New York: Macmillan, 1953), 126.

Return to Reference.

25Waldrop, Rosmarie. Curves to the Apple: The Reproduction of Profiles, Lawn of Excluded Middle, Reluctant Gravities, (New York: New Directions, 2006), 49.

Return to Reference.

26Cooperman, Matthew, Web Conjunctions: Between Tongues: An Interview with Rosmarie Waldrop, by Matthew Cooperman, (Conjunctions. Web. 18 July 2014).

Return to Reference.

27Waldrop, Rosmarie. Curves to the Apple: The Reproduction of Profiles, Lawn of Excluded Middle, Reluctant Gravities, (New York: New Directions, 2006), 97.

Return to Reference.

28Keller, Lynn, Thinking Poetry: Readings in Contemporary Women’s Exploratory Poetics, (Iowa City: U of Iowa, 2010 ), 74.

Return to Reference.

29Waldrop, Rosmarie. Curves to the Apple: The Reproduction of Profiles, Lawn of Excluded Middle, Reluctant Gravities, (New York: New Directions, 2006), 97.

Return to Reference.

30Ibid., xii.

Return to Reference.

31Ibid., 58.

Return to Reference.

32Ibid., 56

Return to Reference.

33Ibid., 54.

Return to Reference.

34Ibid., 62.

Return to Reference.

35Howe, Susan, That This, (New York: New Directions Pub., 2010), 11.

Return to Reference.

36Frost, Elisabeth A., and Cynthia Hogue, Innovative Women Poets: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry and Interviews (Iowa City: U of Iowa, 2006), 160.

Return to Reference.

37Ibid., 159.

Return to Reference.

38Ibid., 160.

Return to Reference.

39Howe, Susan, That This, (New York: New Directions Pub., 2010), 6.

Return to Reference.

40Frost, Elisabeth A., and Cynthia Hogue, Innovative Women Poets: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry and Interviews (Iowa City: U of Iowa, 2006), 161.

Return to Reference.

41Howe, Susan, That This, (New York: New Directions Pub., 2010), 39.

Return to Reference.

42Frost, Elisabeth A., and Cynthia Hogue, Innovative Women Poets: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry and Interviews (Iowa City: U of Iowa, 2006), 161.

Return to Reference.

43Thompson, Jon, “Interview with Susan Howe.” Free Verse - Susan Howe, (Free Verse, Winter 2005, Web. 24 Aug. 2014)

Return to Reference.

44Ibid.

Return to Reference.

45Bervin, Jen, Jen Bervin | The Desert (N.p., n.d. Web. 7 Sept. 2014).

Return to Reference.