An anthropologist may give a hearty laugh here, because misleading a native informant intentionally or unintentionally with questions steeped in the anthropologist’s preconceptions is by no means an uncommon practice in fieldwork. Or, interpreters may insert themselves in the middle of cross-cultural interactions and even invent something as they go along.

– Yunte Huang, Transpacific Displacement1

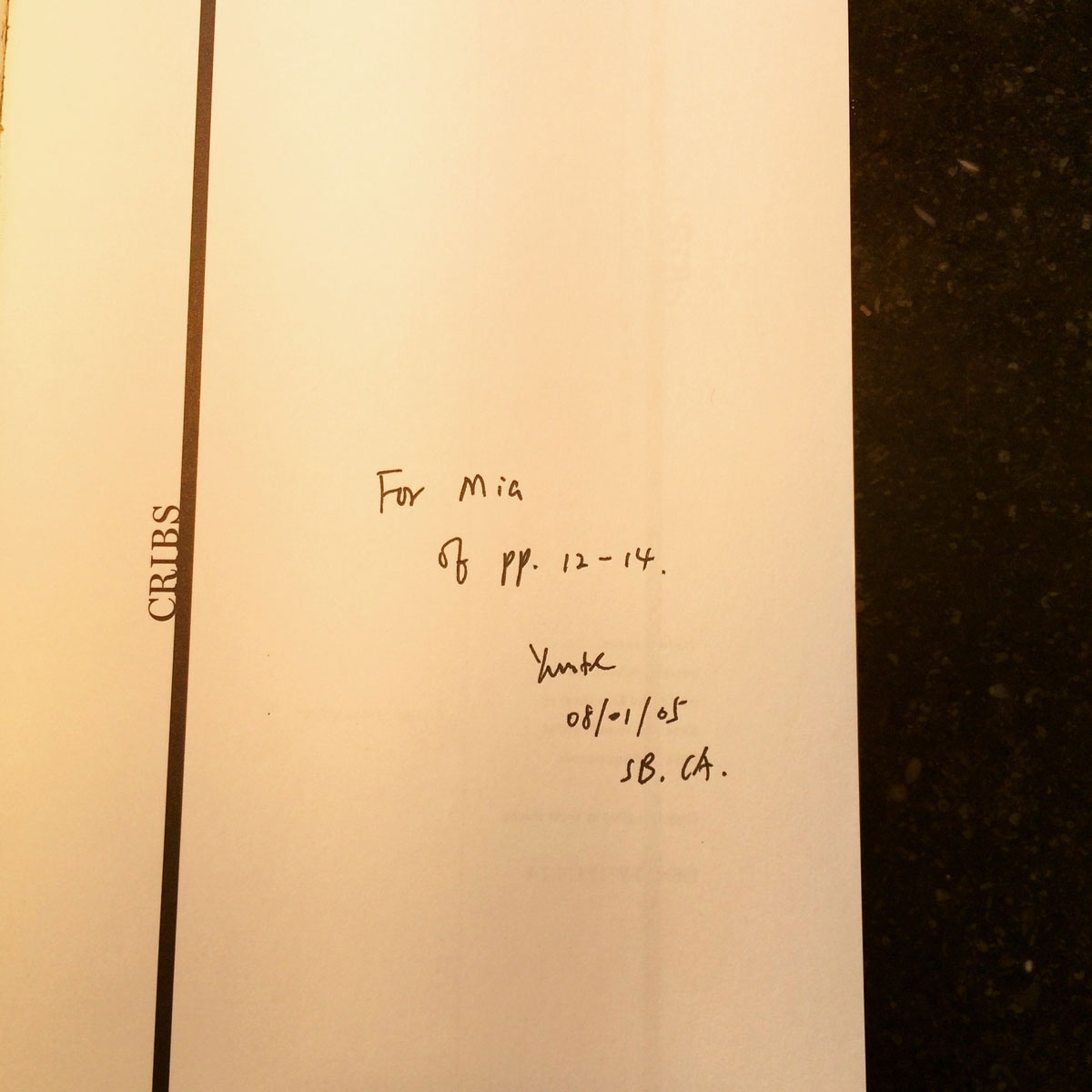

The 2011 conceptual writing anthology Against Expression, edited by Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith, includes a six-page excerpt of Yunte Huang’s Cribs.2 Huang – a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, known primarily for his scholarly writing on transpacific modernism and, most recently, his multilayered and much-acclaimed biography Charlie Chan: The Untold Story of the Honorable Detective and His Rendezvous with American History – originally published Cribs as a full-length collection with Tinfish Press in 2005.3 It is his only poetic work in English to date.

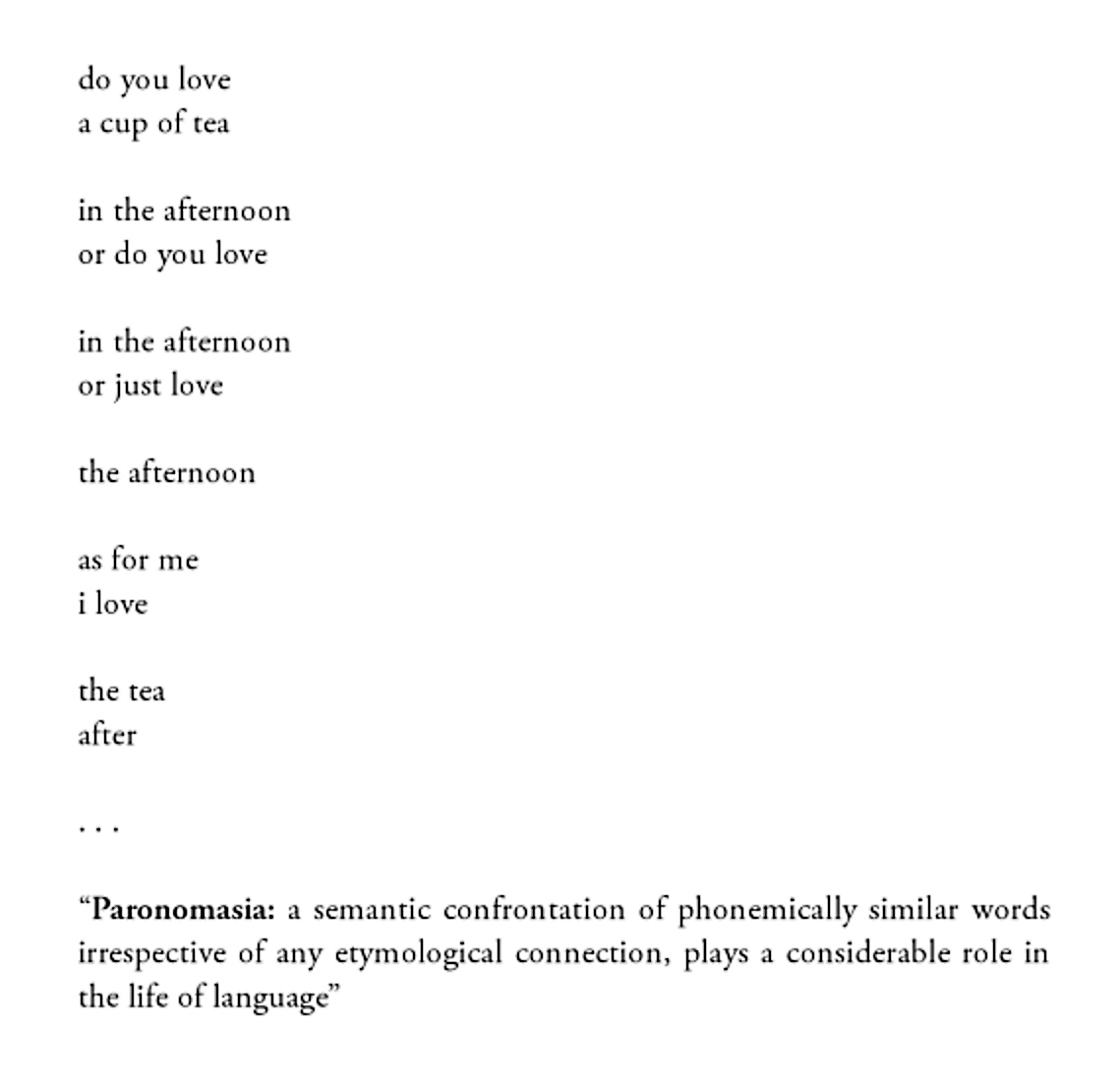

Dworkin and Goldsmith, in their introduction to the anthologized excerpt, describe Cribs as “an extended poetic essay on the manifold denotations of the title” in which “Huang mixes short lyric poems based on anagrams and sound play with unattributed – that is, cribbed – quotations.”4 To illustrate their point, they quote from Huang’s quote from Roman Jakobson: “Paronomasia: a semantic confrontation of phonemically similar words irrespective of any etymological connection, plays a considerable role in the life of language.”5 This definition of paronomasia also appears in Cribs’ excerpt, as such:

Directly preceding “Paronomasia” is the short poem, “do you love / a cup of tea,”6 an elegant and economical undressing of grammar, in which phrases are repeated and cast off, the page’s text and white space twirl and caress each other, until the poem concludes with a wisp of “the tea / after” – Huang’s version of a post-coital cigarette, we have to presume.

While “do you love / a cup of tea” demonstrates a dexterous manipulation of syntax’s possibilities, it is hardly a clear display of, or elaboration on, paronomasia. For that, we have to look to other parts of Huang’s Cribs, especially in a section that is missing here, signified only by the stitching of three small dots:

***

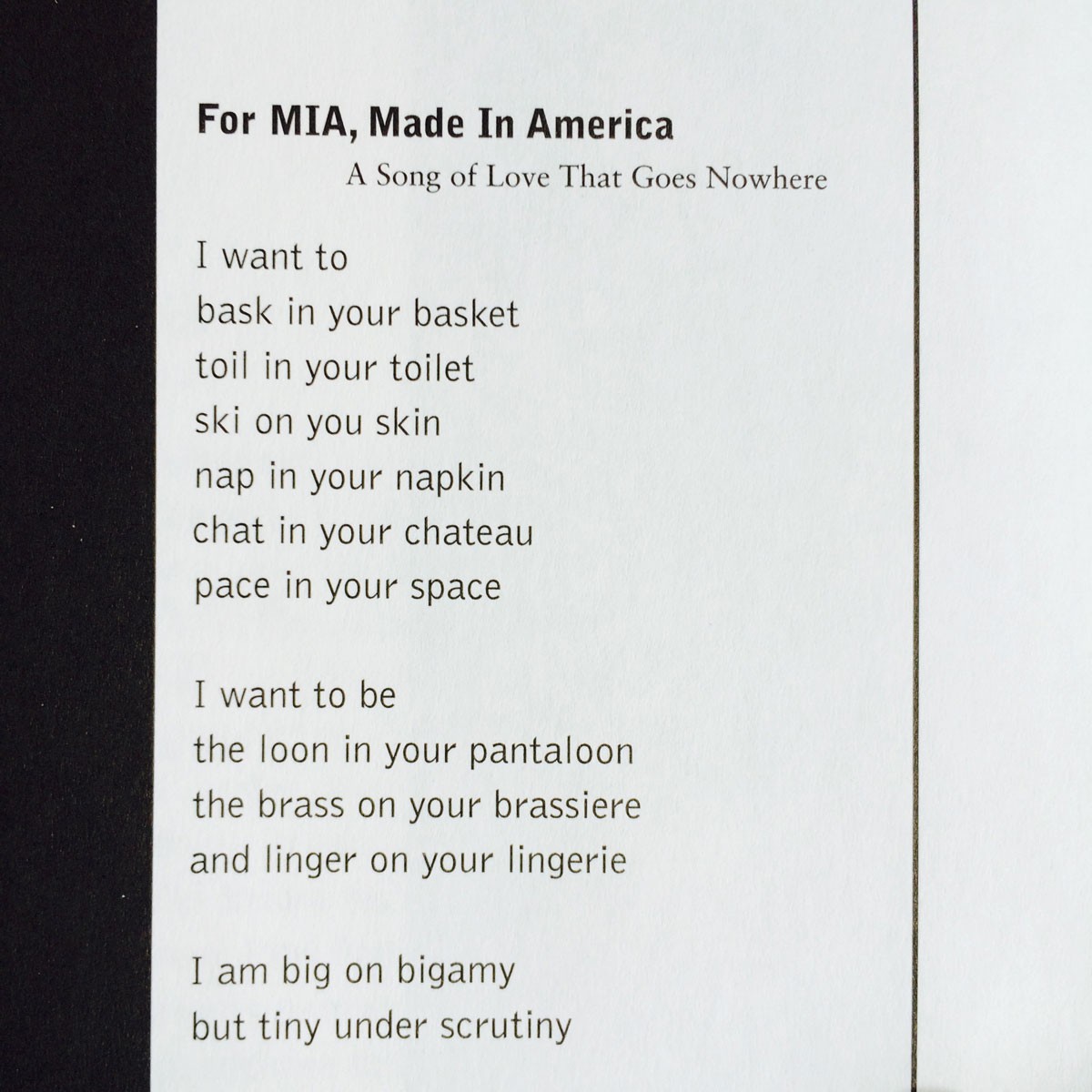

In the 2005 Tinfish book, we find in place of the ellipsis the poem “For MIA, Made In America,” subtitled “A Song of Love That Goes Nowhere.” Totaling three pages, it is perhaps the longest poem in Huang’s collection7, and yet, as the subtitle indicates, it is a poem that appears, both stylistically and content-wise, actually to go nowhere. It begins:

It continues as such for the following 70-or-so lines, as an extended enactment of paranomasiac logic – the language game of extracting words from other words is played over and over again, with humorousness occasionally veering into ridiculousness, and dedication tottering to the brink of obsessive aggression. While the poem’s length is what causes (or impels) these moments we perceive as ridiculous or aggressive to occur, the length is also what keeps them in check, preventing them from determining the totality of the poem’s significance or impact. The absurdity of “I go oral when you are floral” is met with the directness of “anal when you are banal;” the Hallmark cliché of “I am the… mile in your smile” later is countered by the surprisingly revelatory “ritual for your spirituality.”

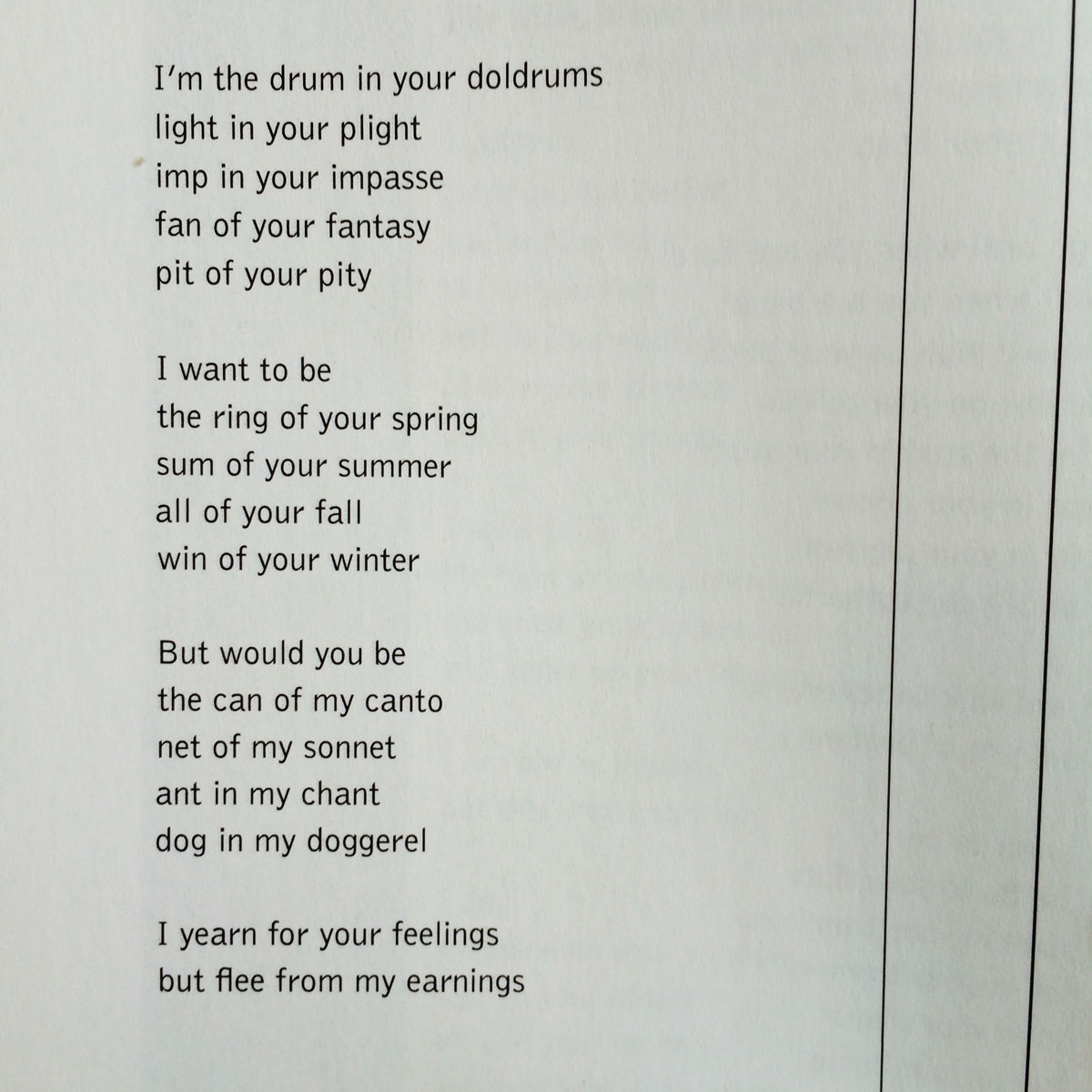

If we were to say that the poem goes anywhere, it might happen during the penultimate stanza, when the insistent projection of the “I” into “your” various attributes flips in the question of what “would you be,” what could “you” become:

This appearance of “you” as the pronoun “you” – rather than the possessive adjective “your,” modifying “your basket” or “your toilet” – offers “you” an independent existence and agency outside of Huang’s language play, a subject “you” that might choose to be or not to be “the can of my canto” or “net of my sonnet.” This possibility of agency, however, is quickly rescinded; the phrase “would you” initially suggests an invitation or solicitation (such as, “Would you like a cup of tea?”), but with the reassertion of “I” comes a new reading of “would you” as a hypothetical or conditional possibility, as the sudden revelation of consequences. “I yearn for your feelings / but flee from my earnings,” the poem concludes. The “I” is saying, in effect, that that the “you” has no possibility of choice; that what appeared to be an invitation is, in fact, the “I” describing another facet of his speculation. The question of the penultimate stanza no longer appears to be, “Would you say yes or no?” but rather, “If you said yes, would I actually want this?” And to this, the speaker appears to decide preemptively, No, thus making “For MIA” truly a song of love that goes nowhere – not even going to the “you” the song ostensibly addresses.

In her review of Cribs for Verse, Victoria Chang recounts, “During a reading at the University of Southern California in February 2006, Huang said: ‘Language is autoeroticism. It reveals itself.’ Language for Huang, an immigrant from China, is not fixed; the land of signs and signifiers is never straightforward or set in stone.”8 If indeed we read “For MIA” to be a love song by an immigrant for America (or for all things “Made In America”), then we might sympathize with Huang’s autoerotic take on the English language: the incessant drive to make paranomasia make sense and to see method in the madness; the glee in extracting one’s own words out of another’s; and finally the fear of reciprocated affection. The American dream might be pervasive and strong, but what would it mean about me if America (the global symbol of imperialism, capitalism and global cultural homogenization that it’s become) actually loved me back?

And so it’s easy to appreciate Huang’s charmingly grandiose and irony-laced claim in this poem, as it is within this book, that America is his new crib, coupled with how he cribs (copies, steals) both to master and to appropriate the governing language around him. Matthias Svalina writes, in a review for Octopus Magazine, “Huang steals the creative possibility of language back from its dominant protectors and gives a new vitality that forefronts its instability.”9 And if America or Americanness, the amorphous abstraction that it is, is the object of Huang’s poem, it’s easy to overlook the speaker’s resistance to allowing it an independent, demarcated subjectivity – and the possibility to articulate its actual “feelings” – as “you.”

We might even laud the subtle argument Huang makes about Americanness here, that it has no straightforward definition and existence but can only be recognized and comprehended as a modifier, that it adapts, evolves and emerges through the nouns it precedes. What is “American?” Whatever it is that brings “American pie,” the “American dream” and American Idol together. In other words, we can read “For MIA, Made In America” as a demonstration of how identity is defined through exemplification; how a subject can only grapple with identity through the elements of exemplification laid in front of him; and how that subject – with enough creative spirit and will-to-power – might be able to take an active hand in defining the possibilities for his own identity by altering and manipulating the elements of a “dominant” other’s. When the speaker says, “I want to be… the linger in your lingerie,” not only do we realize that “lingerie” consists of “linger,” we see the exemplifications of “MIA, Made In America” that the speaker has selected to lay in front of us: the basket, the toilet, the skin, the pantaloon, the brasserie, the lingerie. These, too, might be made in America, even with their foreign-sounding labels (pantaloon, brasserie), as much as the clichéd and obvious “American pie” or American Idol. As Chang writes, “For Huang, poetry is not about a conclusion, an end-point that can be neatly tied into a bow, but rather it is about the playful process of language and all the discoveries and paradoxes along the way.”

***

Language is autoeroticism. It reveals itself. Thus far we’ve read “For MIA, Made In America” as an argument about cultural identity in the guise of poetry; but what if we – for the sake of speculation – flipped this over and read Huang’s lines as love poetry disguised as a socio-political statement? In other words, until now we (and nearly all of Huang’s reviewers) have read the object of Huang’s love song, “MIA,” as simply an acronym for “Made In America,” but what if we instead read “Made In America” as an acrostic for someone named “Mia?” How might this alter the subject/object dynamics at play in Huang’s poem, as well as our sense of what Huang’s determined manipulation of language aims to achieve?

In recent years, certain biographical details have come to light that suggest such a reading is possible, although the question of how significantly biographical research should inflect literary analysis remains. (We should tread carefully here.) On the Tinfish Editor’s Blog, Susan M. Schultz posted an essay on June 15, 2010, titled “Charlie Chan Is Dead and Living in Honolulu.”10 Although the essay is primarily a review of Huang’s Charlie Chan, Schulz, having worked with Huang as his poetry editor, incorporates various personal recollections in her reading. Schulz writes:

A couple of years after Tinfish Press published Yunte’s Cribs, a book of documentary/comedic poems…that featured wild linguistic leaps, he came to [the University of Hawaii] to participate in a conference on translation and to give a reading from his work. It was not an easy time for him, as his marriage was breaking up; I too began to flinch whenever his cell phone rang. He had little privacy during these phone calls because he and his then wife, both Chinese, spoke to one another in English.

Schultz then describes how Huang’s translations from Chinese differ from his own poetry in English; “in Cribs he finds the radicals in English. He unpacks words according to their syllables,” she states, and then to illustrate her point she quotes from “For MIA, Made In America.”

Several questions arise here: one immediately wonders why Schultz was impelled to discuss Huang’s divorce, in a manner that comes across as both slightly gratuitous and painful. How did Huang react in seeing his private life made public this way? Or is Huang public enough about his private life that Schultz’s account is hardly an infringement? After all, Huang did publish a poem that claims to be “A Song of Love That Goes Nowhere” in his poetry collection, while still married. And the most intriguing insight here might be that Huang and his ex-wife, “both Chinese,” speak to one another in English. Is she, or perhaps both she and he, the “MIA” who progressively has been “Made In America,” to the point that they argue in America’s dominant language? Is Schultz implicitly presenting this poem as a commentary on their marriage?

Or is it possible that “Mia” is actually a third party, one that implicitly got wrapped into both the biographical details and the poem, one whose existence and perspective remain obscure under all of this (Huang’s and his reviewers’) writing? If there is indeed such a “Mia,” one wonders why Huang published this poem in his collection, while still married, in a manner that comes across as both slightly gratuitous and painful. How did “Mia” react in seeing her private life made public this way? Or perhaps this poem didn’t reflect her private life at all; perhaps she had never had any such “love” relationship with Huang or, at least, was not aware of any (the real reason why this poem is “A Song of Love That Goes Nowhere”); perhaps there was so little of her actual self in this poem that Huang’s account was hardly an infringement?

And even so, perhaps she felt forced to see herself in this poem, anyway. Perhaps she felt she would always be there implicitly and she couldn’t do anything about it. Perhaps when Huang presented the poem to her – if he did – she felt immediately distressed from the fact he wrote her any kind of “love song” at all, because he was married, because she was his student, and because she was emerging from an actual relationship in which her boyfriend constantly accused her of being unfaithful to him. Perhaps she felt dumbfounded by how lines such as, “I am big on bigamy,” and, “I’m the stud in your study,” could be literally true (at least in Huang’s mind), and that they could co-exist with outrageously false lines that implicated her own body and sexuality, such as, “I go oral when you are floral,” “I am the bell of your belly / nip of your nipple,” and, “I move high on your thigh.” Perhaps the lines that hurt her most were, “I’m the go in your lingo / ink in your think / tune of your fortune / iron in your irony,” because he had introduced her, in fact, to the kind of poetry she saw herself being intellectually devoted to, committing her life to, and these lines seemed to say she couldn’t, wouldn’t be able to do this without him. Perhaps, she thought, I’m smarter than you think, and I see how the speaker doesn’t allow the “you” an opportunity to respond, to exist outside of its attributes. I see how these are all attributes you’ve selected, that have nothing to do with how I would define myself. I see that even though you suggest you emerge and extract yourself from my attributes (that you “steal the creative possibility of language back from its dominant protectors,” as Svalina puts it), nonetheless you begin every stanza, every sentence, with “I.” I see how, in fact, you always come first and that what you claim to be my attributes are those that are derived from you.

Perhaps she also felt slightly embarrassed for both herself and Huang, recognizing that the language game in “For MIA, Made In America” echoed her favorite lines from the 2000 film Bring It On. Perhaps she felt ashamed of how, in college, she had an irrational resentment toward a fellow English literature student named Nick Torrey, because he seemed to her to be the undeserving Golden Boy: the Amherst-bred, fuzzy sweater and corduroy pants-wearing, deeply introverted and nonsensically mumbling teacher’s pet. Perhaps she felt he was “Made In America” in a way she could never be. Perhaps she remembered that one time in college she was very drunk and ran into Nick Torrey in his dormitory and, inspired by Bring It On, yelled at him, “You put the Torrey in NOTORIOUS!” and could see she hurt his feelings.

Perhaps, just a year after encountering Huang’s poem, when she was, in fact, in the midst of breaking up a professor’s marriage and was indeed the “other woman,” she would think about “For MIA, Made In America” and question the moral validity of her earlier outrage. Perhaps, a few years later, after desperately trying out other things, after she finally returned to the poetry Huang had introduced to her, she had to think of this poem every time she repeated the anecdote about Picasso and Gertrude Stein’s portrait, how Stein did not look like it, but Picasso replied, “She will.” Perhaps, years after that, she would move to another country and realize how profoundly and disorientingly “Made In America” she actually was. Or perhaps she wouldn’t. Perhaps she liked the idea of such a poem being such a big part of her life, of poetry being a force that could shape her, but perhaps this particular poem wasn’t. Perhaps she would sit down to write an essay about the whole experience, and once she had, wonder if it (the poem, the essay, the questions, the feelings, the realizations) really meant anything at all.

***

“Cribs is a book of thefts and linguistic mutilations. It is a book of wrong speaking that feels so right,” Svalina writes. “And it’s a book that demands that you not act all serious and morose when you talk about linguistic and culturally political topics. In Cribs it’s all right to be smart and silly.” But what if, as Svalina almost certainly couldn’t have known, these poems are not just about linguistic and culturally political topics – what if, even partially, even obscurely, they are about thinking and feeling objects? How might such an object search for and recuperate an effective way to respond, to see the poem not as against expression, but as a vehicle for her own expression by other means? Because being silly doesn’t quite fit within being silenced. And an “I” disappears in mutilation, if mute. If the poetic affect of Huang’s “For MIA, Made In America” is that “wrong speaking feels so right,” the reactive critical affect might be this: a neutralization through “right speaking” of what once felt so wrong. The critic, after all, can assess the true heft of the theft and indeed be smart in the place of smarting.

Or, at the very least, the critic might give the love song’s obscured object a chance to object with the hindsight and distance of scholarship: an essay on what she wants to emerge from the wanton, and a way to stuff this wonton with everything she won’t, wouldn’t and wasn’t.

Notes

1Yunte Huang. Transpacific Displacement: Intertextual Travel in Twentieth-Century American Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. 45.

Return to Reference.

2Yunte Huang. “From Cribs.” Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual Writing. Ed. Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2011. 301-306.

Return to Reference.

3Yunte Huang. Cribs. Honolulu: TinFish Press, 2005. The back cover features a blurb from Marjorie Perloff, who writes: “Huang shows himself to be a unique master of the language game… What the Russian Futurists called <<the word as such>> is here displayed in all its possibilities.” Another blurb, from Rob Wilson, adds, “Cribs proffers a brave, mock-heroic, colorful space of neo-textuality.”

Return to Reference.

4Against Expression, 301.

Return to Reference.

5Roman Jakobson. “Quest for the Essence of Language.” Diogenes 13, no. 52 (1965). 21-37.

Return to Reference.

6Huang, Against Expression, 303.

Return to Reference.

7Several of Huang’s verses are untitled and begin with “ * ,” leaving ambiguous whether they are short, individual poems or sections of a much longer poem. Thus, assessing the relative length of “For MIA” is difficult.

Return to Reference.

8Victoria Chang. “NEW! Review of Yunte Huang.” Verse, July 18, 2006.

Return to Reference.

9Matthias Svalina. Review of Cribs. Octopus Magazine, Issue 8.

Return to Reference.

10Susan M. Schultz. “Charlie Chan Is Dead and Living in Honolulu.” Tinfish Editor’s Blog, June 15, 2010.

Return to Reference.