It is raining. Let this book therefore be, above all else, a book about ordinary rain.

—Louis Althusser, “The Underground Current

of the Materiality of the Encounter”

· Two Photographs, One Missing ·

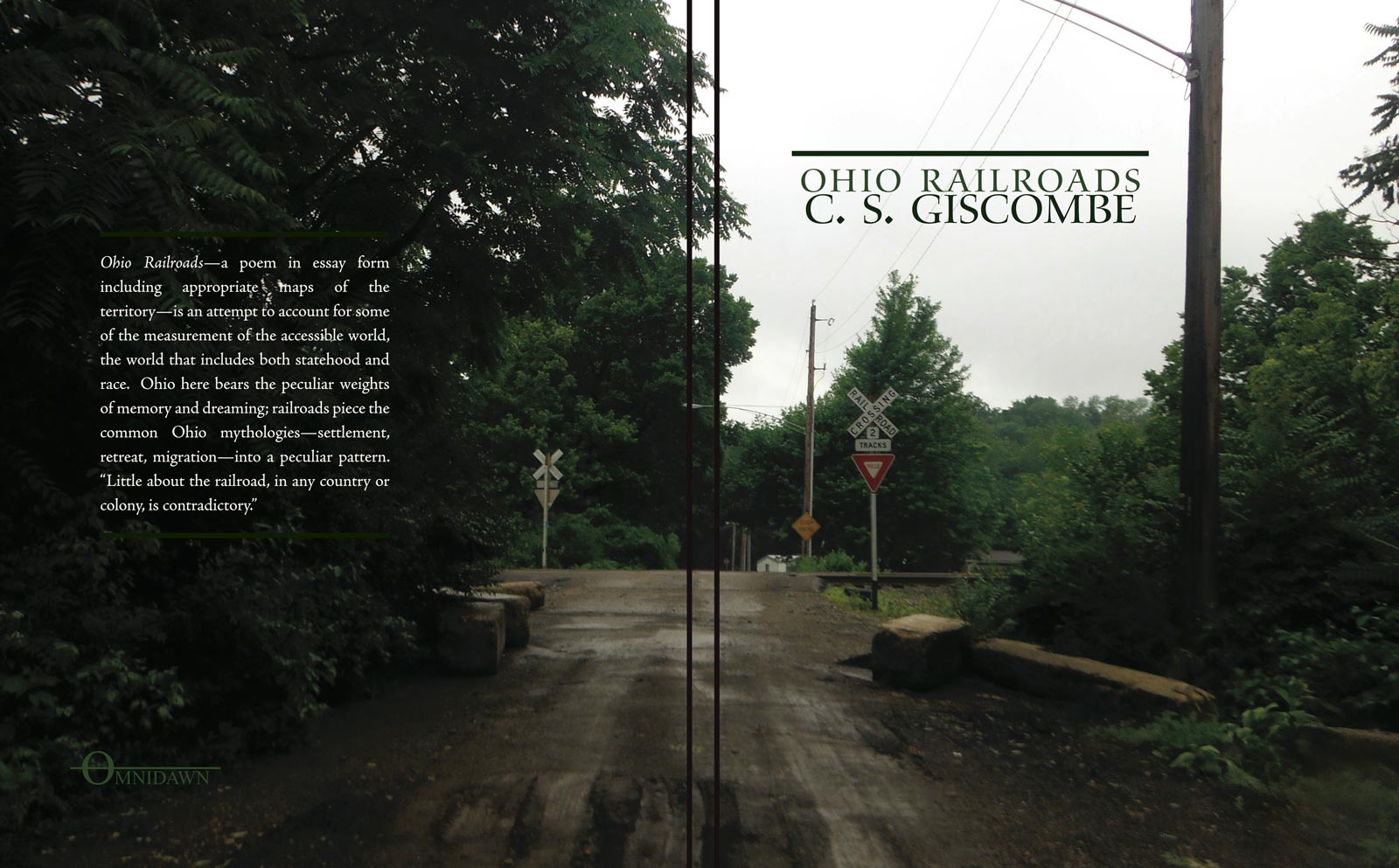

The photograph on the cover of Ohio Railroads, C. S. Giscombe’s latest chapbook, features a wet dirt road facing a railway crossing, their intersection marked by a warning sign we later learn is called a “crossbucks.” We are somewhere in rural Ohio, perhaps on the outskirts of Dayton, Giscombe’s childhood home and the hub of this book’s social geography. The scene is dense and empty—dense with overgrowth lining the road and empty of trains, cars, and people, an absence mirrored by a patch of characterless grey sky. The crossbucks sign is itself a fractured picture poem, one word “CROSSING” and therefore breaking another in two: “RAIL/ROAD.” In effect, this is the history of railroads, as well as an emblem of poetry: both are dense weaves of connection without a presiding unity, every linkage accompanied by breakage and loss. If this photograph provides entry into Ohio Railroads, it also bars the way forward, planting the crossbucks before us, reinforcing that obstacle with a “STOP AHEAD” sign further down the road, and then dropping the scene’s vanishing point—framed squarely by the camera for our eyes1—behind a dip in the road beyond the tracks. The image announces that the book we are about to open won’t cooperate with any expectation that the way forward will be smooth.

But what kind of book is Ohio Railroads anyway? And how does it bear on a discussion of “affect and poetry”? The back cover calls it “a poem in essay form,” and the only self-reference within the work identifies it simply as “this writing.”2 By turns a fact-laden history of Southern Ohio and its railway systems, a somewhat sparser history of black Dayton, and an intermittent memoir of childhood place, the book also bears a relation to elegy. It begins by recalling a dream in which the poet foresaw his “mother’s death falling, indistinguishable from rain, on a railroad bridge” in downtown Dayton (7). Toward book’s end, the poet describes driving his mother’s Toyota Camry to that very bridge the day after her death. Between these two moments, information accumulates—about trains, about Dayton, about the Giscombe family (though rarely about the mother)—all delivered without formal differentiation in a “matter of fact” prose characterized by its nearly complete lack of inflection. Across the fifty-two pages of Ohio Railroads tone hardly varies; there is no rise and fall. For all its obsession with detail, this book’s voice remains continuously level, too flat even to be called “melancholic.” This is what voice would sound like if voice were asphalt worn by many years of rain.

In lieu of closure, the poet describes a photograph he took with a cellphone camera at the scene of the railroad bridge associated by dream with his mother’s death. Unlike the photograph on the cover, this one is not reproduced and only described (was it lost? erased?): “The tracks and ballast are a grey and brown blur across the bottom of the photograph and the blue sky and its white clouds, the bulk of the photograph, are nearly one texture” (46). We understand that the unrevealing nature of this scene is somehow the product of all the dense social and personal history that precedes it (again: density and emptiness). Elsewhere Giscombe has spoken of “the hulking hollow nature of things” and “the peculiar emptiness there is to big events.”3 Less conspicuous is that the image doubles as an index of prose style itself: monochromatic (grey and brown); uniformly even (nearly one texture); devoid of individuation (blurred, “a history of mergers” [10]); and imprinted by large impersonal systems that meet at this very point but come from elsewhere (tracks below, weather above). Giscombe withholds the photograph not only to emphasize the distance fused into a loss that ought to be intimate, but also in order to describe it—in order, that is, to produce a sentence barren of everything but its descriptive function. Like a camera, this language records a specific point of view that is information-rich but unaccompanied by any particular affect or interiority. The remarkable thing about Ohio Railroads is that while it could only have been written by C. S. Giscombe it also testifies to the insubstantial nature of its own localized point of view. Here the impersonal voice is not a triumphant aesthetic alternative to the messiness of historical subjectivity (the escape from contingent personality promised by Eliot and, in a way, also by de Man); it is rather a way to inhabit history’s grey inevitability and the massive material deposits it leaves, even as it thins human presence to the greatest possible degree.

According to Rei Terada’s influential theory of emotion, there is a thermodynamic economy of pathos that makes emotion inescapable, for even the would-be absence of emotion has its own oddly satisfying texture—what Keats called “the feel of not to feel it.”4 For that reason we shouldn’t take the impersonal pose of affectless writing at face value: it often amounts to little more than the wishful refuge of a subject seeking relief from its unhappy condition. Regarding Ohio Railroads there are two things to say in response. The first is that Giscombe makes no pretense of excluding emotion altogether. More strangely, he acknowledges emotions in a way that renders them as slight and inconsequential as possible. Referring to his experience as a railroad engineer, he recalls how “I would hate crossings like the one on Mound Street” (36) in Dayton, with its risky blind spot. Here is a subject with memories and emotions. But the passing remark reveals nothing private or singular and it quickly gets absorbed into the real topic at hand: railroad crossings and Mound Street. This turns Wordsworth’s famous dictum about lyric poetry upside down: rather than action and situation being the occasion for feeling, here incidental feelings fade into an infrastructural world whose durable materiality overwhelms them. The emotion gets depleted right to the verge of its disappearance. Instead of presenting a world without emotion, as if that were possible, Giscombe tracks interiority as it undergoes erasure.5

Approaching affectlessness in this way—and this is the larger point—Ohio Railroads looks very strange against the pervasive “affective turn” that currently dominates literary and academic culture.6 At a time when the emotions are being asked to do so much work (as a counterpoint to instrumental and administrative reason, as a reversal of pernicious mind-body dualisms, as a future-oriented agent of innovation, transformation, or anticipatory longing), this prosaic poem asks nothing of emotion. If it is an elegy replete with references to cemeteries, funeral homes, and burial mounds, it is an elegy stripped of consolation (especially the consolation of lyric form and meter). If it is an act of “cognitive mapping,” it pursues that work without the political agenda or urgency driving Jameson’s cartography of late capitalism.7 As a social history, it has nothing to do with “structures of feeling”—the term widely borrowed from Raymond Williams to suggest that we register the absent causality of history in the present as a dynamic affective experience prior to conceptualization.8 According to this view, historicity is a cognitive dissonance one feels. The material atmosphere of clouds and weather moving across the globe and bearing the consequences of past events from distant, diverse places has its correspondence in the shifting affects and moods that respond to these complex, nebulous motions right beneath the subject’s threshold of cognition. In Ohio Railroads, structures pile upon structures, but there are no such structures of feeling, no useful intuitions of historicity to be gleaned from consulting the feelings. History does not hurt, it greys and numbs. The initial dream rain that falls “indistinguishable” from the mother’s death and the periodic references to weather that follow (“Rain in Ohio generally originates in low-pressure systems in the southern and western parts of the U.S.” [46-7]) have their closest analogue in the ancient atomism of Lucretius, who described atoms falling insensibly through space:

Now here is another thing I want you to understand.

… atoms move by their own weight straight down

Through an empty void.

If [a swerve or clinamen] did not occur, then all of them

Would fall like drops of rain through the void.9

If our recent affective turn is part of a larger tendency to affirm the generative, “thing-powered” vitality of a new materialism, then the materialism of Ohio Railroads dials down the affects and entails no affirmation.10 In this book, the rain that raineth every day does nothing for us. To come as close as writing can to its sourcelessness, its inevitability, and its cumulative mass and force is what Giscombe calls “railroad sense” (51). This kind of materialism—which I want to call mere materialism—offers no affective payoff, not even the uplift of stoic apatheia: “railroad sense” can only be recorded by diminishing sensibility and adopting a more mechanical sensitivity, like that of a camera taking in tracks and sky. History of this kind is not interiorized as affect. It is entirely exterior—the accumulation, friction, and deterioration of surfaces.

· History without Persons ·

In groundbreaking poems like “Michael” and “The Ruined Cottage,” Wordsworth established a lasting protocol for narrating affective history in lyric form: identify some meager material remains that any passerby would barely notice (“a straggling heap of unhewn stones” in “Michael”; “four naked walls / That stared upon each other” in “The Ruined Cottage”) and tell the story that “appertains” to them, thus reanimating the ruins by recalling the heartbreaking histories of those who lived and suffered in these now desolate sites.11 Ohio Railroads does the opposite: rather than bringing Dayton’s forgotten past to life it heaps up names, details, and anecdotes in order to foreground the environmental build-up that surrounded, shaped, and (though subject to decay itself) outlasted human presence. The movement in this book is always from persons to material processes and large inorganic structures. The Dayton Flood of 1913, which left three hundred dead, becomes an occasion to name and locate all six flood-control dams subsequently built as part of the Miami Conservancy District. A sketch of family events preceding the Giscombes’ purchase of a “farmhouse at 161 Liscum Drive” (29) fades into a historical geography of places and institutions connected to Liscum Drive, the sprawling Veterans Administration campus most prominent among them. But rather than taking on “a life of its own,” the administered and infrastructural world of Ohio Railroads becomes a layered archive of inert entanglements: all that remains of its human history is a palimpsest of names. Dayton is a ghost town without even the ghosts to animate it.

A typical passage follows the CSX and Norfolk Southern Cross rail lines out of Dayton along the Miami and Mad River valleys, mentioning local historical figures of note en route: future president William Henry Harrison; Tecumseh (who figures prominently in the book and whose confederation Harrison defeated at the battle of Tippecanoe); George Armstrong Custer; and one Oliver “Pappy” Henderson. Like the railroad system itself, everything in this discourse develops by contiguity; its information seems undermotivated; its juxtapositions reflect accidents of place and appear without comment: “Henderson was called ‘Pappy’ because he was older than the other pilots in his squadron. Tecumseh had been born on the Mad River, at old Piqua, in 1768” (13). Henderson’s presence is as close as this text comes to comic relief: he is the pilot supposed to have flown dead space aliens from their Roswell, New Mexico crash site to Dayton in the late 1940s. Giscombe quotes Henderson telling his daughter they were “humanoid looking, but different from us” (13). Placing Henderson’s silliness alongside Tecumseh abbreviates a long national history that runs absurdly from Native American dispossession to the popcultural conspiracy theory of those who still believe that the Wright-Patterson Air Force base outside Dayton “houses alien bodies” (12). But that last phrase is also surprisingly resonant, for Ohio Railroads compiles a history that could indeed be said to “house alien bodies.” This history summons the names of those who (unlike Wordsworth’s Michael or Margaret) are not resuscitated through memory, testimony, and sympathy and are instead made to appear “different from us,” flatter and emptier and irretrievable—in a word: “gone.” Another emblem of this thin history occurs when Giscombe describes how the architect of the VA’s Dayton National Cemetery, Captain William B. Earnshaw, relocated “the remains of thousands of dead soldiers”—or, as Giscombe puts it, “disinterred and reburied them” (30). That is how each historical name works in Ohio Railroads: it disinters the dead only to rebury them.

Consider the case of Paul Laurence Dunbar, “born in Dayton in 1872, the son of former slaves,” and “best known” today “for his dialect poems.” Over the course of two pages (19-20), we learn that Dunbar’s mother did laundry for the Wright brothers’ family; that Dunbar was friends with Orville Wright in high school; that his New Orleans born wife had attended Cornell and written essays on Wordsworth and Milton there. Each datum is as flat as it is fascinating, and all are leveled by the text’s gravitational pull away from human activities and toward the urban constructions or institutions that “housed” them. Dunbar’s work as a student editor draws attention to “old Central High School,” his time as an elevator operator to “the Callahan Building at Third and Main Street.” Dunbar’s retroactive celebrity eventually earns him a street name: North Summit Street becomes North Paul Laurence Dunbar Street. An area nearby becomes “the Wright-Dunbar Historic District, a focus of urban renewal in the 1990s.” Altogether, the effect is to chart Dunbar’s disappearance into a name, his becoming as paper-thin as a map crossed by railroad lines. The passage concludes with an unadorned description of an engineered but depopulated world:

The Pennsylvania track crosses North Paul Laurence Dunbar Street at an angle of approximately seventy degrees; the tops of the tracks are flush with the pavement’s surface for a very long distance. The street is a north-south running street and the railroad line is parallel to Wolf Creek, which flows southwest from its source near Brookville, until it joins the Great Miami by Riverview Park downtown. The crossing on North Paul Laurence Dunbar Street was protected, in 2008, by a pair of flashing lights that dates from the 1940s or 1950s; the bridge over the creek lies just beyond the crossing. (20)

If maps could speak for themselves perhaps this is what they would sound like.

Not all of Ohio Railroads sustains this extreme objectivity. How could it? Even the steady paratactic flow of information has been sifted and selected, and subjective judgments occasionally show themselves: Preble County is “profoundly white” (35); a particular railroad crossing is singled out for its beauty—“broadly-situated, graceful, well-marked” (34). We see through Giscombe’s eyes. But for the most part in Ohio Railroads, point of view rarely organizes the scene; the scene (itself overdetermined) organizes the point of view. Intimate, real-time experiences are in fact historical and environmental, already “mapped.” This inversion begins with the opening sentences, where the “I” that dreams, remembers, and sees gives way to the object of dream, memory, and sight: the Dayton railroad bridge where the mother’s death was falling, indistinguishable from rain. The unwieldiness of this object creates a problem for vision: whether one views it from Third Street or elsewhere, no empirical prospect can encompass its length, for it is “a single bridge across the whole of downtown” (9). If “it’s necessary … to see the whole structure” (9) it’s also impossible to do so. Thus the same bridge whose “high cement sides” cast a “shadow” over the poet’s whole “life” (42)—as Giscombe puts it in the only piece of verse printed in Ohio Railroads—is also a determining condition whose totality cannot be perceived. For those living in its shadow, the bridge embodies a collective space that subtends every sensory event even as it remains beyond the reach of anyone’s comprehension.

To suggest this programmatic quality within experience, Ohio Railroads sometimes reconstructs local, transient perceptions as if they were optical events available to anyone on specific, recurring occasions. Dayton is a segregated matrix of streets and tracks built up slowly over time; this evolving transportation system organizes and distributes the public’s movement through space; that regularity in turn produces sensory experiences that have more to do with time and location than with irreplaceable individuals.

Approaching on Third Street from the west one would come to the intersection with Summit Street and suddenly have a view of both the crossing and, beside it, the larger Kroger chain store which, with its excavated hillside parking lot, was an anchor of the West Side commercial district; the intersection was the top of the Third Street hill (as Summit Street’s name would suggest) and the downtown skyline, beyond the river, was also visible from there. Trains seemed to dwarf the Kroger store as they passed next to it. (18)

The charming optical illusion requires a subject to perceive it, but no subject in particular. It is the subject position, momentarily filled by any passerby, that matters. When the Dayton National Cemetery began to shelter mourners with “large striped tents,” “internments ‘caught the eye’ of passersby in automobiles or those riding trolley buses on West Third Street” (30). These visual events are transpersonal and replicable effects. They are like the recycled phrases (“caught the eye”) that ventriloquize individual speech and can therefore be marked as citations. Even singular events that imprint themselves on memory can be traced to a structural backdrop that made them possible. When a constable tracks a fugitive along Linscum Drive, Giscombe and family “watched from the porch,” observing “a rail-thin white man with grey hair wearing a plaid shirt, [who] stalked the fence with a large pistol in hand, his fingers outside the trigger” (31). But before the sentence containing this striking image has come to an end, it has already opened (via a semicolon) onto an account of a jurisdictional dispute between Dayton and Jefferson County (the Giscombes lived near the border) that led both municipalities to dispatch officers to the scene he observed as a child.

In these images, memory and perception converge in a way that is both individual and generic, the experience of a person who is also a placeholder. Perhaps the most concentrated rendering of this function occurs as a stand-alone memory in a one-sentence paragraph:

As a child I would sit in the Wilkes & Worth Barbershop on West Fifth Street and gaze at the trains crossing Mound Street—the track was two blocks south of the shop’s plate glass windows—while the barbers and my father argued about national politics and about the contradictions of Negro life in Dayton. (36)

What could be an origin story for the poet’s fascination with trains is both precisely located and almost entirely without content. Had one been there, at that time and place, this is the kind of thing one would have seen: trains passing, if you were on the inside looking out; a local genre scene of men debating politics and race, if you were on the outside looking in. On either side of “the shop’s plate glass window” lies a tableau. That window, tucked casually into a parenthetical insertion right at the center of the sentence, is pivotal, in spite of (perhaps because of) the transparency that leaves its glass almost invisible. The window conditions (frames) what can “catch the eye,” and its flat surface mediates between whatever we experience on either side of it: interior recession or outward extension. It is like a camera looking inward and outward—or like a prose medium that reduces everything it makes visible to description.

· A Thing of Visual Moment ·

One last scene from Ohio Railroads, quoted in full:

During the year that my mother was dying I dreamed of walking from West Third Street up a hill, at the top of which was a railroad crossing protected by crossbucks which had caught the light of the sun. A crossbucks, or crossbucks sign, consists of two white arms that form an X—on the arm that extends from the lower left to the upper right is printed the word CROSSING and on the other arm is the word RAILROAD, which is broken into two words—RAIL and ROAD— by its intersection with the unbroken word, CROSSING. Waking, I realized that the dream was, in essence, a memory of a scene I noted many winter mornings on my way to high school on the city bus. The bus route, Route One (Drexel westbound, Third Street eastbound), ran from one end of Third Street to the other end. Between its intersections with Gettysburg Street and Abby Street it paralleled the Baltimore & Ohio’s line to the Veterans Administration campus; the track was on a ridge slightly above Third Street and a quarter mile to its south and it skirted the grounds of a housing project. On those mornings the sun, low to the horizon, would illuminate the metal arms of the crossbucks sign, visible from my usual seat on the Third Street bus. This had been a thing of visual moment. (38-9)

This aesthetic flash of sunlight on a crossbucks sign is typically personal and structural. Catching the student’s eye and subsequently recurring in dream and memory, it is also the consequence of an unthinkable chain of events that includes complex infrastructural developments (railroad tracks, surface streets, bus routes, racial demographics, and school systems) as well as the blind planetary motions that allow for low sunlight on winter mornings in Midwestern towns like Dayton. The convergence of these vectors gives the intersecting arms of the crossbucks sign the status of an objective correlative. From this event, we learn nothing special about teenage psychology or even about this teenager’s psychology; after all, anyone in that bus seat, on that route, at that time of day and year might have seen the same superficial and transitory effect, the indifferent result of light reflecting off a metal surface. So what does it mean when Giscombe, in the flattest of this prose poem’s routinely flat statements, says, “This had been a thing of visual moment”? Was this moment momentous, not visual but visionary? Was it akin to Blake’s “moment in each day that Satan cannot find” or to Woolf’s “moments of being”?12 Or does the sentence’s emphasis fall on its pluperfect verb tense, the “had been”? This radiance mattered once; it transmitted an affective charge, but now no longer. Or is the sentence merely neutral and descriptive, devoid of elevation or pathos? “This had been a thing of visual moment” and nothing more—literally, an optical effect regularly produced by this particular conjunction of time, location, and a receptive retina. Perhaps the momentary flash of “free beauty” or “pulchritude vaga” (Kant’s terms) is not a release from the greying world of mere materialism but just another manifestation of it.13

Without further comment, Ohio Railroads does what it always does: it picks up a contiguous element from the surrounding scene and moves on, this time returning to the adjacent housing project briefly mentioned when situating the crossbucks illumination. The next paragraph begins: “The housing project was called Arlington Court.” Two sentences later: “The project’s gone now and the site has been leveled into a blank space” (39). Given that this observation immediately follows the text’s closest approximation to a visual revelation, it seems justifiable to hear the word “sight” folded into this “site,” for both perceiver and perceived are vacated almost as soon as they are identified.

· Endnotes ·

1This emphatic centering is evident when front and back covers are spread to display the entire photograph.

Return to Reference.

2C. S. Giscombe, Ohio Railroads (Richmond, CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2014), 45. Further citations appear parenthetically.

Return to Reference.

3“PhillyTalks 18” (2001), a conversation with poet Barry McKinnon, archived at the PennSound website of the University of Pennsylvania. The site includes a text of the program (see p. 18). “PhillyTalks 18” is also forthcoming in C. S. Giscombe, Border Towns (Dalkey Archive, 2015).

Return to Reference.

4Terada, Feeling in Theory: Emotion after the Death of the Subject (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2001), 13-14. Keats, “In drear nighted December,” 21, in The Poems of John Keats, ed. Jack Stillinger, (London: Heineman, 1978), 221.

Return to Reference.

5Contrast this evacuation of person, voice, and emotion with Giscombe’s quite different description of what it was like to be an African-American train engineer with a prosthetic arm in his essay “On a Line By Willie McTell.” There the speaker revels in anomalous singularity: there is “no descriptive word or phrase for what I was on the train; … on the railroad I was something else … I extended myself beyond the normal into the fictional, the synthetic, without resolution. No Garden of Eden for me, baby; no circling back.” In Beauty Is a Verb: The New Poetry of Disability, ed. Sheila Black, Jennifer Bartlett, and Michael Northen (Cinco Puntos Press, 2011), 262-267.

Return to Reference.

6The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social is the title of a collection of essays edited by Patricia Ticineto Clough and Jean Halley (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2007), but both the topic and the phrase have been pervasive for at least fifteen years now—and not only in books published by Duke.

Return to Reference.

7For “cognitive mapping,” see Frederic Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1991), 54.

Return to Reference.

8For “structures of feeling,” see Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1977), 128-135, and Kevis Goodman’s groundbreaking application of this concept to those affective disturbances in poetry that register “the flux of historical process” (10) in the present: Georgic Modernity and British Romanticism: Poetry and the Mediation of History (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004), 1-16. Also see Mary Favret, War at a Distance: Romanticism and the Making of Modern Wartime (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2010), 57-58, and Thomas Pfau, Romantic Moods: Paranoia, Trauma, and Melancholy, 1790-1840 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2005), 29.

Return to Reference.

9Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe, trans. Ronald Melville (Oxford: Oxford World Classics, 2008 [1997]), II. 216-222, p. 42.

Return to Reference.

10Jane Bennett describes her oft-cited new materialism as an attempt “to give voice to a thing-power.” Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2010), 2.

Return to Reference.

11Wordsworth, “Michael,” 17-18, in Lyrical Ballads 1798 and 1800, ed. Michael Gamer and Dahlia Porter (Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview, 2008), 386; and “The Ruined Cottage,” MS. D, 31-32, in The Ruined Cottage and The Pedlar, ed. James Butler (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1979), 45.

Return to Reference.

12Blake, Milton 35:42, in The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David Erdman (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 136. In “A Sketch of the Past,” Woolf describes past moments so vivid they “can still be more real than the present.” Moments of Being, ed. Jeanne Schulkind (Mariner Books, 1985), 67.

Return to Reference.

13Kant, Critique of the Power of Judgment, ed. Paul Guyer, trans. Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000), 114-116.

Return to Reference.