Excerpts from a blog written in the third person, during residence in Hiroshima, summer, 2008.

May 22—Magpies, Butterfly Wings, Bamboo

When you level a city—literally destroying everything except for a few buildings and 60 trees in a city of over a million—killing 100,000 people instantly, you leave a population wanting things—beds, clothes, their children, toys, technology, anything to hold onto. She felt guilty and just wanted to go take pictures even though everyone knows that pictures do not alleviate guilt or fix things. Photographs only show the same thing again and again, proliferating the problem or making the problem pretty.

Hiroshima Storefront near the Train Station, 2008

She had never expected to live in a building built by the US military right after the atomic bomb was dropped—built for soldiers and American scientists to study—not help—the victims of her country’s crime. The ABCC (Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission that became a joint operation with the Japanese in the 1970s, renamed RERF, Radiation Effects Research Foundation) is perched on a hill overlooking Hiroshima, next to the Museum of Contemporary Art. It is an old compound—a little rusty and abandoned even though plenty of people still work there. The people of Hiroshima do not like that the compound is up there—so out of the way and difficult for the survivors to get to and on such precious land. As far as she could tell, the American government had no plans to move it. She feels guilty for even being here.

ABCC (Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission) being built on Hijiyama Hill, Hiroshima; Archival photograph from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, 2008

RERF (Radiation Effects Research Foundation, previously the ABCC), from the dormitory, 2008

The birds, with their deep caws, woke her family up at sunrise and they ventured out onto the roof to watch the day begin. The kids love watching out for the wild cats—strays with bloody wounds on their necks, limps, various disfigurations or odd features—crazy fur, wild eyes, plump paws, skinny backs.

May 23—Anticipation

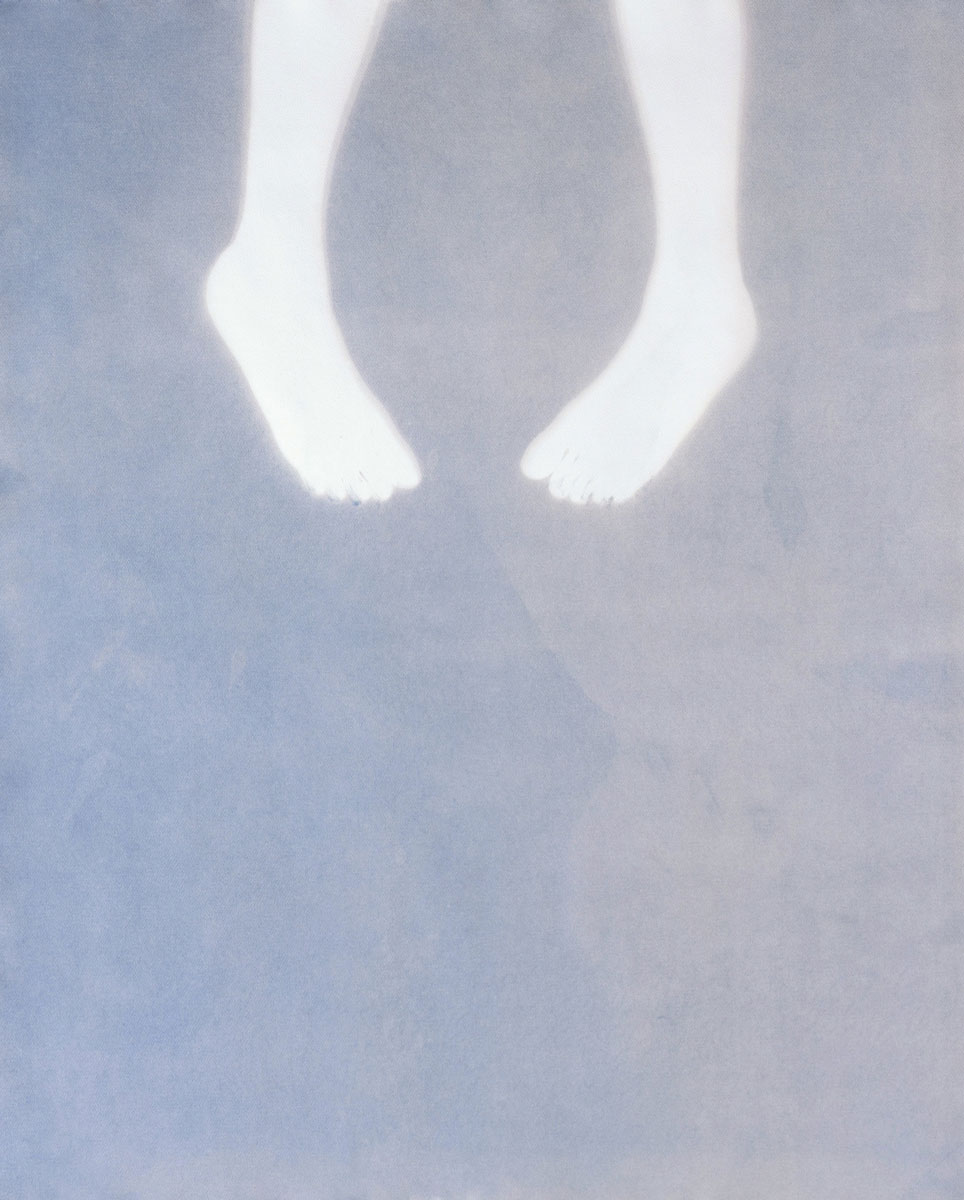

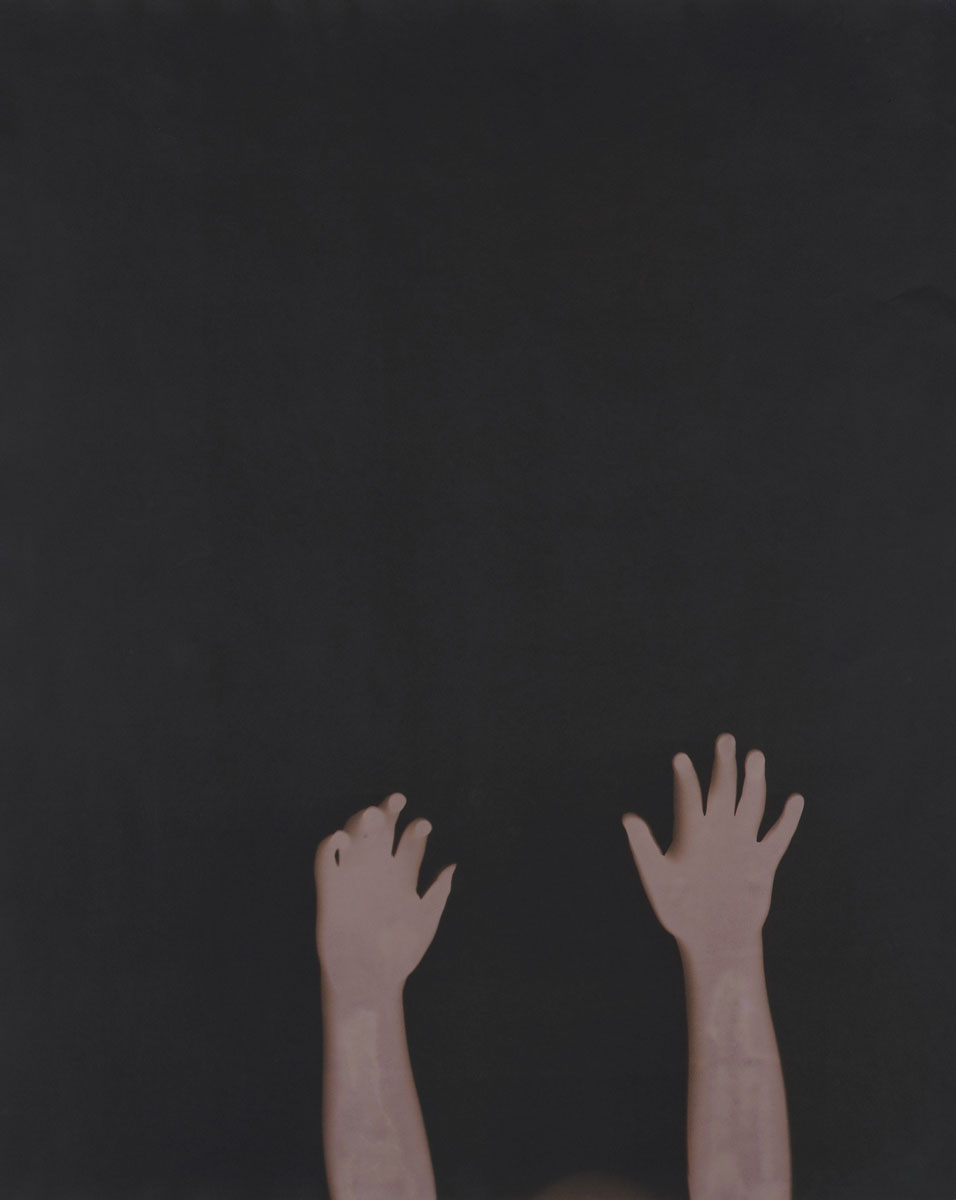

She wants to walk along the river, roads, buildings, neighborhoods, and see it all, rub it all, photograph it all. She wants to get inside, to find the spoiled objects that will leak onto x-ray film—leaving ghostly explosions of light in the darkness, to place flowers on the little cyanotype paper she brought with her that will leave white shadows.

Howard Zinn’s wife died last week. She emails the famous and kindest historian she will ever meet to send her sympathies and love and is astonished that he emails back with love and joy that she is in Japan—a place that every time he was here he found it extraordinary.

May 24—Being American

She is struck by the monolithic concrete buildings everywhere. She understands that this was all built after the bomb that destroyed everything and that was what the time dictated—1950s modernism, a concrete jungle, brutalism, bunker mentality. She notices that when she makes statements to other Americans about the atomic bomb or her protests at Fort Benning Military Base against The School of the Americas, they do not respond. An American in Japan, she does not feel like an American.

While taking pictures of groups of schoolgirls singing at the monuments in the Peace Memorial Park, she hears the voice-over from a film in the Peace Museum, “In the searing flash, I became a picture. Blasted by the heat, I melted into the wall. Blasted by the wind, you disappeared into the earth.”

Schoolchildren singing at the Children’s Peace Monument of Sadako Sasaki holding a bronze crane,

Peace Park, Hiroshima, 2008

She cries several times while in the Peace Park—once while listening to the English audio at the Tower for Mobilized Students, and throughout the two devastating documentary films she watches in the museum: A Mother’s Prayer from 1990 and Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Harvest of Nuclear War from 1982. Both films have footage of a two year old girl heaving and crying out for her dead mother and roving shots of the dead, skulls, burned bodies, keloids, deformities, destroyed cities, everything completely obliterated and yet, the miracle of a kind of survival for some. A young girl fans the ashes of her father in an urn, wishing to cool him. He was a fisherman and died three days after being exposed to the atomic tests on the Bikini Atoll. In Hiroshima, all things atomic are connected. Sadako, the girl who died of leukemia while folding thousands of her medicine wrappers into paper cranes; another girl who was damaged by radiation at the moment of conception would never understand the damage. “There is no cure for the atom bomb.”

She is stunned by the footage of grasses, flowers and ladders, and yes, even people, burned white onto the surface of wood and stone, negative shadows like Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes. Can’t believe that she feels even more than she already felt about these absences, these atomic ghosts. She not only wants to make cyanotypes, but also do rubbings of flowers, grasses and ladders.

Film still from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, 2008

May 26—We Know Full Well…

It was only 21 days after the first atomic bomb test in Alamogordo, New Mexico that the U.S. dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima and then just a few more days after that when they dropped Fat Man on Nagasaki. They wanted to see and study what the atomic bomb would do to people on the other side of the world. It was a criminal experiment. She wanted to listen to Joy Division’s “Atrocity Exhibition” and when she saw footage of the countless charred bodies and the emaciated survivors, she had flashbacks to other footage—footage of the concentration camps—another war, another war the U.S. was involved in.

This drawing takes as its reference an aerial photograph from the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archive of the crater formed by the first atomic explosion. On July 16, the Trinity test was the first test of a nuclear weapon conducted by the U.S. on what is now White Sands Missile Range. The detonation is credited as the beginning of the Atomic Age. Shortly after this test, The U.S. dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima and Fat Man on Nagasaki.

We Are Our Own Enemy, Alamogordo, New Mexico, USA 1945 from Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography, elin o’Hara slavick

The atomic bomb called Little Boy “dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 turned into powder and ash, in a few moments, the flesh and bones of 140,000 men, women, and children. Three days later, a second atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki killed perhaps 70,000 instantly. In the next five years, another 130,000 inhabitants of those two cities died of radiation poisoning. Those figures do not include countless other people who were left alive, but maimed, poisoned, disfigured, blinded.

Hypocenter in Hiroshima, Japan 1945, from Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography, elin o’Hara slavick

A Japanese schoolgirl recalled years later that it was a beautiful morning. She saw a B-29 fly by, then a flash. She put her hands up and “my hands went right through my face.” She saw a “man without feet, walking on his ankles.”—Howard Zinn, Hiroshima: Breaking the Silence

The Japanese people have attempted to make maps from memory of the destroyed neighborhoods at ground zero—neighborhoods that were once full of artists and doctors, actors and writers. She was struck by the pinkness of one of the handmade Hiroshima neighborhood maps. It was the same pink as her own drawing of Hiroshima. She is troubled by the name of the park—“Peace Memorial Park”—as if peace has vanished and we can only remember it, not live it and she supposes that for the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, this is ultimately and absolutely true. She is troubled by the fact that such a brutal slaughter is the reason for this park where children sing and picnic and tourists come with paper cranes and cameras.

Opaque cataracts; only plasma cells remain; to damage young tissue is to damage young lives; we have to bear the responsibility because we know full well …

May 28—No Good War, No Bad Peace

She decides to go into the Peace Museum this time with hundreds of school kids. She can barely see the soft and thin clothing on display, the black rain on a white wall, the utensils and melted bottles. The schoolchildren take notes. The U.S. dropped the A-bomb to “justify expenditures.” Dummy A-bombs were called pumpkins. There were children called bomb orphans (who shined the shoes of westerners). The ABCC (Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission) was formed in 1947 and the Japanese people had this to say about it, “They examine us but they do not treat us.” Hibakusha (A-bomb survivors or explosion-covered people) say simply, “I met with the A-Bomb.” As of 2007, there were 251,834 Hibakusha in Japan, 78,111 in Hiroshima. “A woman passed water from her own mouth to mouth of her mother before she died.”—Yoshio Hamada (text describing the print he made as an Atomic Bomb Survivor).

There is no such thing as a good war or a bad peace.

June 1—Kissing A-Bomb Trees

She is waiting for cyanotype paper to arrive from the states so she can make sun prints of various flowers and plants of Hiroshima, especially leaves or bark or twigs that have fallen from A-Bombed trees. Yesterday her daughter kept kissing the A-Bombed trees, saying, “I am sorry. I wish I could take you home.”

Harper Ursula’s feet, slavick’s daughter, 2012

Guthrie’s Hands, slavick’s son, 2012

June 3—Dandelions

Hiroshima Dandelion, 2008

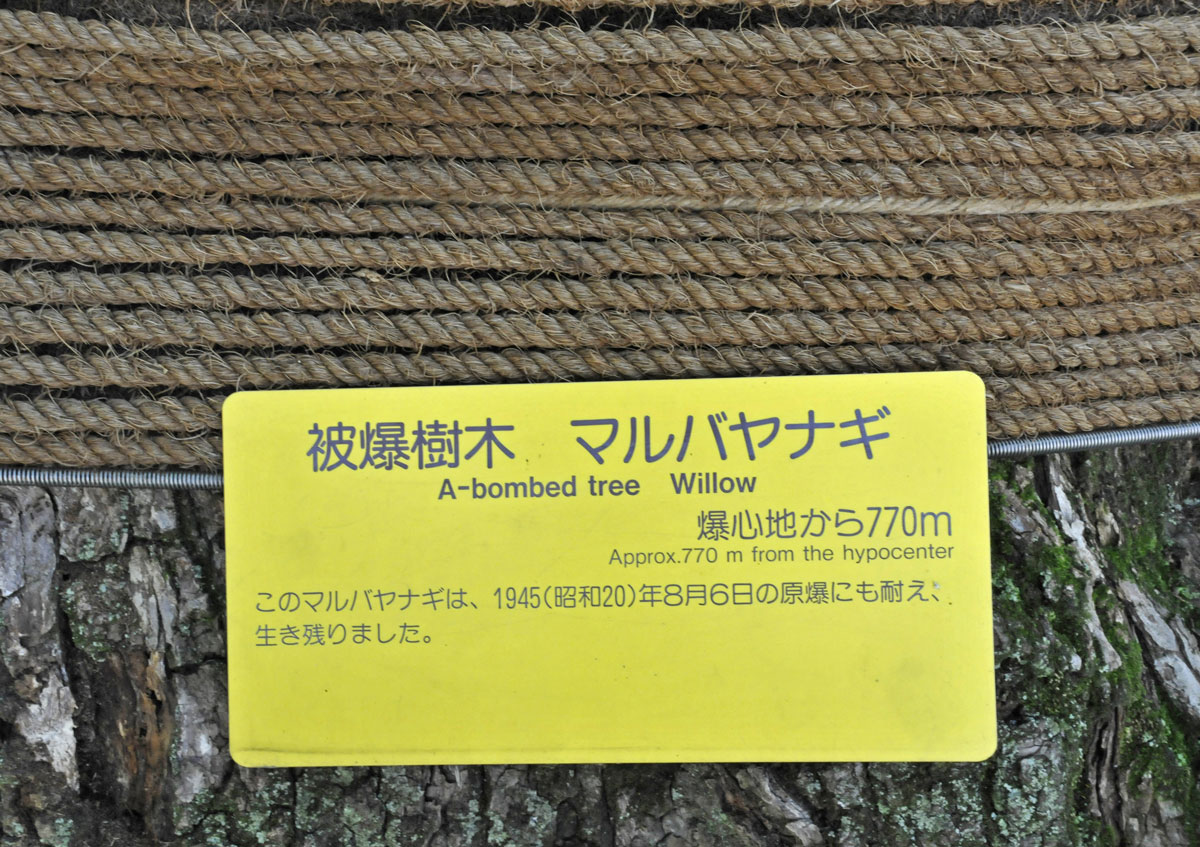

Today she collected fallen leaves and damp bark from the A-bombed Eucalyptus tree at Hiroshima Castle. She cried when she walked around to the back of the tree and saw it literally weeping thick burgundy tears, bleeding. She made a rubbing of the trunk. One Japanese man walked by and said “beautiful.” She also did a rubbing of the burlap ropes tied around the A-bombed Willow tree. She managed to do lots of rubbings today: the 1930s wooden floor and walls pockmarked with shards of glass at the old bank—one of the only remaining buildings after the A-bomb—now an exhibition center. The current show is of a million paper cranes heaped and hung and arranged in aisles. She reads about “horseweed” growing wildly shortly after the A-bomb. This is what people boiled to eat out of necessity. What is horseweed?

A-bombed Eucalyptus and Willow Trees near Hiroshima Castle, Hiroshima, 2008

Wednesday, June 4, 2008

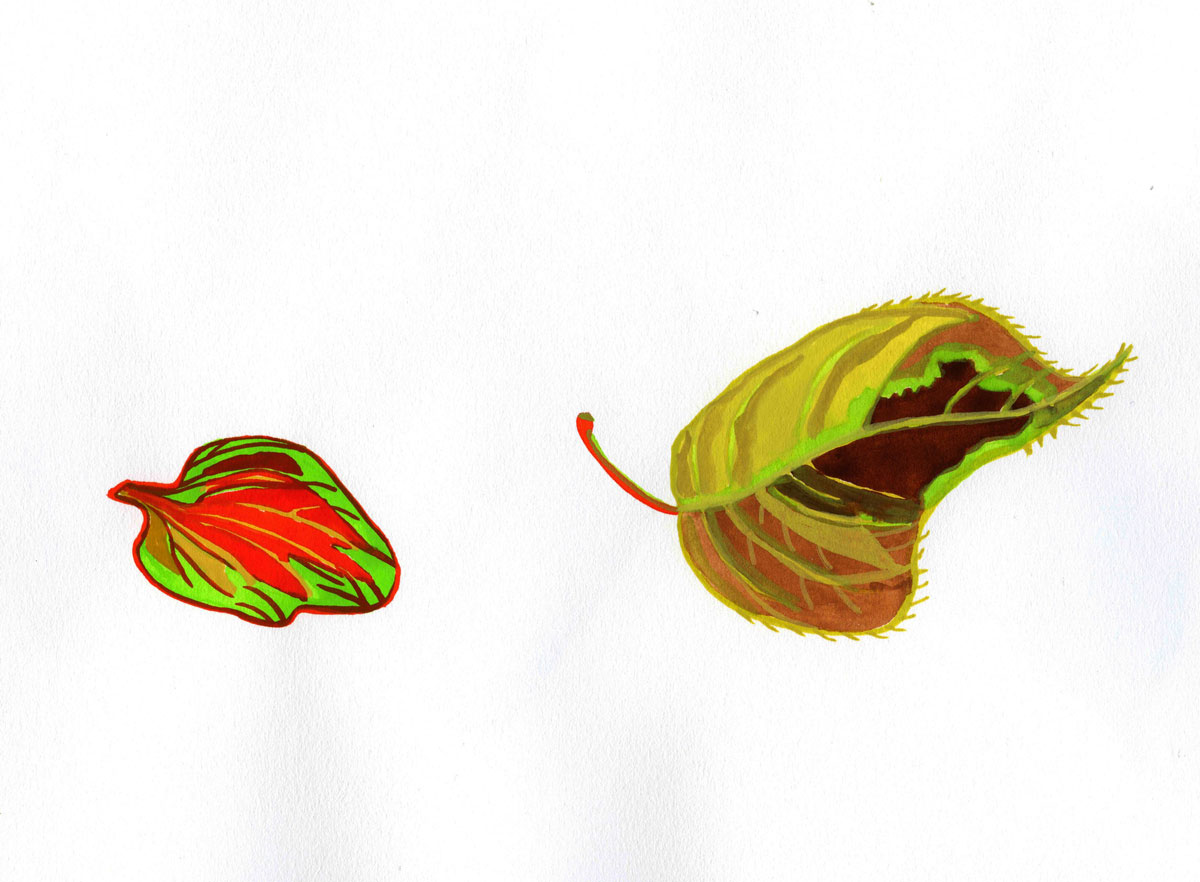

She returns to the A-bombed Eucalyptus tree and takes lots of photographs of the bloody stigmata in the trunk of the tree. There are actually several, all eye shaped and oozing. She is painting more leaves from her walk and has begun taking photographs of dandelions about to blow away. She may take photographs of 1,945 dandelions for Hiroshima: small, fragile balls of wishes, wispy, tiny stars, blossomed, blooming, so temporary.

Gouache on paper of Hiroshima leaves, 2008

Friday, June 6

Her husband thinks she should figure out the average number of “blooms” on each puffy dandelion head so that each photograph of each dandelion would represent that number of victims of the A-bomb, rather than photographing 1,945 dandelions—which is too many and could defeat “the power of the small gesture.”

She gulps down Roland Barthes’ Empire of Signs at night. She underlines most of it and writes in the margin. What is opposed to representation and writing—just being? She feels as if she is missing half of what Barthes is writing—the half about emptiness and Zen, signs and language. Maybe she is missing all of it but she relates to it—the fictive, foreign country, the absence of recognizable symbols, the impossibility of the Orient.

June 8

A curator talks about how the A-dome has become a capitalist tourist attraction rather than a true symbol and beacon for peace. The curator explains that the hill she lives on and that the museum is on is considered the border between everything that was destroyed and rebuilt and the older sections of the region. She also explains that one of the reasons the city built Hiroshima MOCA on the hill was to reclaim it as their own—in opposition to RERF.

Harper and Guthrie, slavick’s children, at the A-bomb Peace Dome, Hiroshima Peace Park, 2008

Atomic Mask, cyanotype of fragment of steel beam from the Peace Dome, Hiroshima, 2008

She is reading Barthes and wants to copy entire passages into this diary but is too tired. She should do more rubbings tomorrow—of the bank floor and wall, A-bombed trees, monuments. She is not sure she needs to photograph more dandelions. She has been given permission to photograph the Peace Memorial Collection for one day but she is going there on Tuesday to meet with the Director of the Peace Culture Foundation and will try to push it. She really wants to make long x-ray exposures of the objects which can not be done in one day. But she will do what she can. Most people are very discouraging about her idea of making x-ray exposures of objects because it is unscientific. There is no way of knowing if the radiation is just “background radiation” or residual radiation from the A-bomb. She wonders if this really matters? David does not think it matters. Radiation is radiation. And radiation in Hiroshima takes on a whole different meaning regardless of its origin, doesn’t it? But she still does not have x-ray film or a translator. The Geiger counter DID tick tick tick as the held it out at a gravestone nearby …

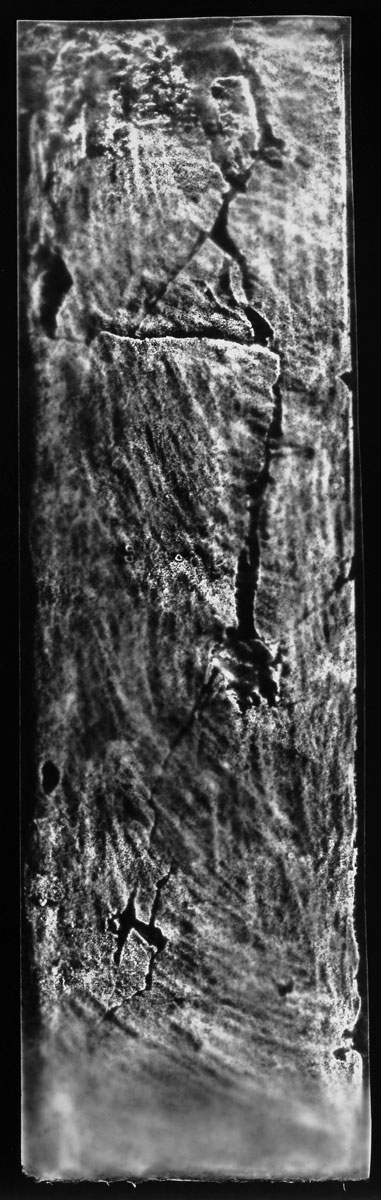

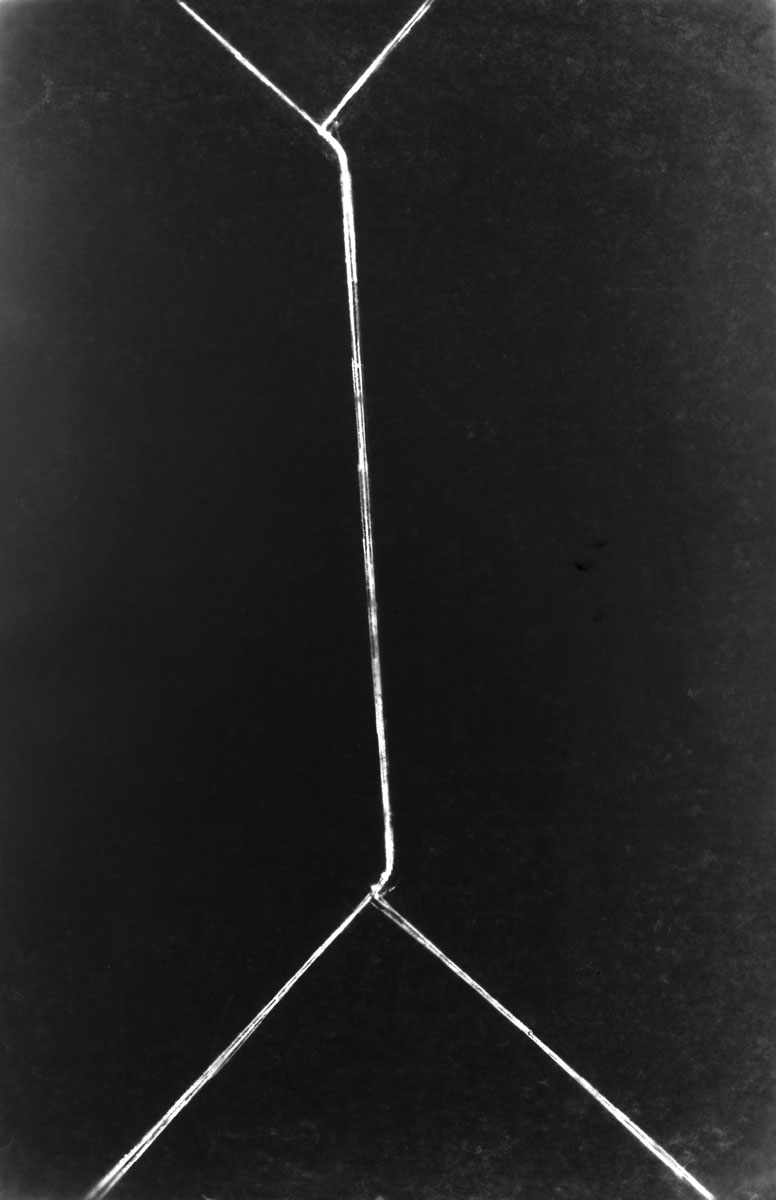

Lingering Radiation, autoradiograph made by placing a fragment of an A-bombed tree trunk on x-ray film in light-tight conditions for 10 days; processing the x-ray film and contact printing the x-ray film on photo paper in the darkroom, 2008

June 10—Jackpot!

She then goes to her meeting with Steven Leeper, Chairperson and Director of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation—the first American ever to hold this position. They immediately become friends because they share friends in common—Arjun Makhijani and Alice Stewart. He really wants to meet her husband to discuss RERF and David’s research findings. They talk about Hiromi Tsuchida’s photographs, Hiroshima Mon Amour, RERF, art and her projects.

slavick making cyanotypes of A-bombed artifacts from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum Archive in the “Sunshine Garden,” Hiroshima, 2013

They sit at a table and she is astounded by their hospitality and generosity. She can not believe when they bring out files with color photographs of melted glass bottles, burned roof tiles and ceramic insulators and ask her which ones she would like to use in her experiment. It takes Steven a while to explain her project to them—that she wants to place these “A-bomb exposed” objects directly on the x-ray film for a long exposure to see if the film registers any radiation. She expects it will—some sort of abstraction, explosion, trace, mark, scattered pattern of contamination, still, even after so many years. Steven explains that no one—especially RERF or the city of Hiroshima—wants her project to “succeed”. They have spent a lot of time and effort convincing people that Hiroshima is now safe. RERF claimed—and still does—that only people within 2 kilometers (recently changed to 3.5 kilometers) within 2 weeks of the A-bomb have cause for concern. (Citizens need two witnesses that they meet this criteria to receive a passbook, essentially a card for free health care.) He tells her about a recent delegation of American woman. Two of them stayed in Tokyo because they were pregnant and were worried about being exposed to Hiroshima. He suggests that she use a lead box during her exposures to rule out any background radiation. She needs to get some highly sensitive blue x-ray film as soon as possible so she can begin this experiment.

June 12—Cracked Marble

Today she kept whispering to herself, “I love Japan,” as she rubbed her soft paper with black lumber crayons over the old Hiroshima Bank floors, cracked marble teller counters and walls. Somehow the bank withstood the A-bomb—one of the only buildings to do so—and was actually used as bank until 1992. She wonders why the security guard suddenly got angry with her at the bank as she was about to do another rubbing of the floor. He was the same one she photographed the week before and who had been so friendly and had given her approval today to do more rubbings. He angrily crossed his arms into a forbidding X and said, “too much time. too much time.” She packed up her paper in her big black tube.

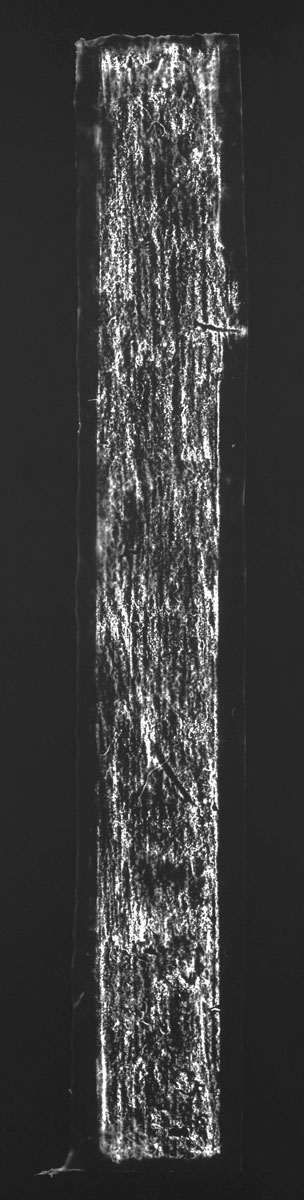

Former Imperial Bank of Japan, an A-bombed building used until 1992 as a bank, now a cultural exhibition center where slavick held a solo exhibition in 2013; a contact print of a rubbing of the floor inside the bank, 2008

June 13—Haikus and Eels

Woman with Umbrella on the Island of Miyajima, near Hiroshima, 2008

Barthes Forbids Tourists from Writing Haikus (but here are two):

Cell phones, umbrellas,

everyone has something

against loneliness.

This tourist haiku

will do nothing but pass time.

This is what she wants.

She can not believe that after rubbing two A-Bombed trees and beginning her hungry way home for lunch, she runs into friends on their way to their parents’ restaurant. She tags along to see where it is so she can try it some day and then Emi invites her to join them! She feels so lucky and even more so when they step inside the perfectly Japanese restaurant. They eat bowls of rice topped with Anago—river eel—with dishes of scallions and wasabi to add if desired, pickled things, little bowls of soup with miniscule mushrooms, floating herbs and seaweed, small dishes of tofu and bean sprouts and an amazing bowl of sardine sashimi served with ginger paste, and green tea from her grandmother’s land in the country. Over lunch she learns that her friend’s grandfather started the restaurant after the war. He had been in Manchuria when the bomb was dropped and he lost everyone, absolutely everyone in his family. She tells her friend that he was lucky to have been in Manchuria but they look at each other and both know that it is very unclear if he was lucky or not. What does it mean to survive everyone you love, to lose them all in a criminal flash?

Glass Shard from the A-bomb lodged in the wood at the former Imperial Bank of Japan, Hiroshima, 2008, contact print of a rubbing

June 16—Michiko, Sadako, Hypocenter

After dropping off the kids she quickly walks over to her favourite A-Bombed Eucalyptus tree in Hiroshima Castle park to collect more fallen leaves and bark that smell so damp and medicinal. She sent off all the ones she collected before to a show in New York City called The Audacity of Desperation—one in each brown envelope with “A leaf from an A-Bombed Eucalyptus Tree, Hiroshima, Japan,” written across the front in pencil. Across the back were alternating texts: “May all nuclear weapons be dismantled; May we bring an end to war; May we know a better world; The Geiger counter ticks as I hold it out to gravestones in Hiroshima; There is no such thing as a good war or a bad peace; A young girl fans the ashes of her father in an urn, wishing to cool him; There is no cure for the atom bomb but to abolish it.”

She had arranged a guided English tour of Peace Memorial Park for 10:30 in the morning with Michiko from the World Friendship Center. They meet in the lobby of the Peace Museum and begin their tour, their friendship. Once again she is struck by the kindness and generosity of strangers. The tour is supposed to last 1 and a half hours but they end up spending the entire day together. Michiko knows everything about Peace Park, the A-bomb, survivors, victims, Japan’s history, the peace movement. She freely shares it all as a volunteer with the Quaker organization World Friendship Center—a non-political, non-religious organization. (She wonders how this is truly possible, especially for someone like Michiko—a Christian and anti-war activist.)

Hypocenter, Hiroshima, contact print of rubbing of the sidewalk and sewer valves, Hiroshima, 2008

Michiko is beautiful. She cannot believe Michiko is 60 years old. She looks no older than 40. Her energy is amazing, soaring, open and from the heart. Most of the following is taken from her notes while Michiko talked. The Peace Park is very close to the hypocenter which is marked by a simple granite monument and explanation text in front of a hospital. It was a hospital before the A-bomb and it is still, rebuilt of course. The hypocenter neighborhoods were the most thriving. There were six neighborhoods, many temples and shrines, businesses, entertainment houses, and homes. After the A-bomb, when practically everything in this area was leveled and everyone died, there were few resources to rebuild. Hiroshima asked the central government to restore Hiroshima. Four years later, in 1949, the Hiroshima reconstruction Law was passed. The Peace Park is an expression of lasting desire for peace. Human bones were found everywhere, unidentified, they were cremated.

Hiroshima was occupied until 1952 by the U.S.-Allied Forces. People came back to Hiroshima because they knew nothing about the radiation. The occupying forces maintained a high level of censorship and incorrect information. A-bomb survivors built about 450 shacks that had to be destroyed in order to make Peace Park. It took time to remove these shacks but the government built simple homes for the survivors that ultimately were removed as well in the 1970s for museums and shopping centers.

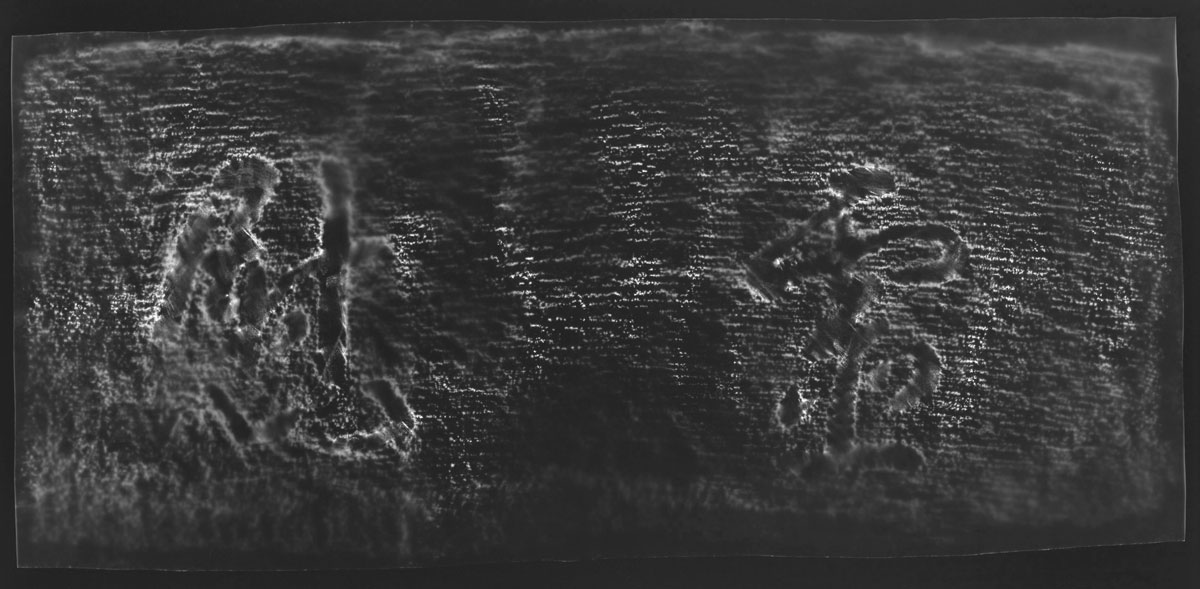

Leaf from the A-bombed Chinese Parasol Tree, cyanotypes, 2008

Leaf from an A-bombed Chinese Parasol Tree, contact print of rubbing of front and back of leaf, 2008

They stand at a Chinese Parasol Tree that survived the A-bomb elsewhere and was transplanted to Peace Park. The obvious injury faces away from the hypocenter because trees must be replanted in their original direction. There is also a second generation Chinese Parasol Tree beside it. The quick regeneration of plants and trees, seemingly perfectly healthy, was an encouraging sign to the survivors after the A-bomb. She is struck by the large and beautifully shaped leaves and hopes she can do a rubbing of the damaged trunk of this tree and have a leaf to x-ray and make a cyanotype of. Survivors are now planting seeds of A-bombed trees. She wonders if the seeds or trees have been tested for radiation.

Supposedly Hiroshima City tested the area on October 1, 1945 and they were surprised by the low level of radiation—probably due to the typhoons shortly after the A-bomb that washed so much away—lives, shacks, soil, poison. Hiroshima City now claims that the level of radiation in Hiroshima is “as low as somewhere never bombed.” She does not believe this.

There is a monument to the poet Sankichi Toge. Even though the occupying forces forbid the use of the word “A-bomb” on monuments or otherwise, Sankichi Toge managed to publish poems and magazines against the A-bomb, renouncing war. In 1950, while in a hospital, Toge heard that Truman was thinking about using the A-bomb again—this time against Korea. He responded by writing A-bomb poetry, raging against war. He died during one of many operations. His fountain pen and hair are buried beneath the monument. (She plans to go find his books tomorrow.)

Comfort Souls, contact print of rubbing of memorial on Ninoshima Island, 2008

The Monument to Prayer simply says “Comfort Souls,” which is what many of the monuments say. Michiko says there are three reasons for the monuments: to comfort the souls of the dead; to remember; and so we never repeat this episode. The Prayer Monument was erected on August 15, 15 years after the A-bomb to console the victims of the A-bomb.

Centotaph, Hiroshima Peace Park, 2008

There are 258,000 names of A-bomb victims registered under the cenotaph. Each year on August 6, new names are added. They walk back to the Peace Park and visit the basement of the rest house—one of the few buildings to withstand the A-bomb. Only those who speak Japanese and who know about this basement can go. You must ask and fill out a form. One man survived the A-bomb in this basement. He had gone down to get some papers. At 8:30 - 15 minutes after the A-bomb, he managed to be standing on the edge of the bridge, observing burning hell. You must wear a hardhat to go into the damp and dark cellar. Walls are cracked, large puddles soak the cement floor, rusty doors and wooden barriers stand as evidence of history, as witnesses to it. Some people have left paper cranes and other offerings here. It is haunting. She feels the weight of survival.

The basement of the Rest House where Mr. Nomuro Eizo survived the A-bomb, 2008 (notice the steel door on the right)

Envelope Door, contact print of rubbing of steel door in the A-bombed basement, 2008

They come out into the blazing light and sit on a bench near the Sadako monument—by far the most popular in the park. People are always there—singing songs, taking pictures, ringing the golden crane bell, leaving paper cranes, praying, crying. Michiko asks her if she wants to know the real story of Sadako. Of course she says yes, but she wonders what she is saying yes to. Michiko had met Sadako’s father before he died. He told her about how Sadako’s mother held her tight in a boat as they tried to escape, but the black rain fell and fell, soaking Sadako’s kimono. The black rain was radioactive poison. He told her that even though every story of Sadako—and there have been many; her story has been translated into over 30 languages—claims that she almost managed to fold 1,000 paper cranes—1,000 being the magic number that according to Japanese tradition would allow your wish to come true, she actually DID fold 1,000 cranes and had begun to fold another 1,000! They talk about this decision—to tell the whole truth, the real truth, or half the truth. Does one offer less hope than the other? She is convinced that the whole truth should be told. The truth only makes Sadako stronger and the story even more moving, devastating, real. Folding 1,000 paper cranes will never cure leukemia, but one girl can change the world.

Sadako Sasaki in her coffin, archival photograph from the Hiroshima peace Museum, 2008

June 27—Mitaki Temple Heaven

The entire temple grounds survived the A-bomb and the outrageous orange pagoda, built in 1162, was moved in 1951 to the grounds to comfort the souls of the victims of the A-bomb.

There are ashes from Auschwitz buried on the grounds, along with the ashes from A-bomb victims. A plea is etched in stone for all of us to integrate humanity more fully into lives …

June 30—Strings of Time

Saturday morning, she and David went to the Hall of Remembrance to hear an Hibakusha (A-bomb survivor) speak about her experience. She was 8 years old when she saw the sky blast and rip open and turn her world into ashes, death and poison. The following are notes she took as the translator spoke:

“I was 8 years old when the bomb was dropped. In 10 seconds everything in a 2 kilometer radius from the hypocenter was burned. The winds from the blast, heat rays and radiation were the 3 elements that destroyed everything. Radiation was scattered in a 4 kilometer radius. 70,000 people died instantly. Another 70,000 died by the end of 1945 (140,000!).

It has been 63 years since the bomb and 4,000 people are added each year to the registry of victims of the A-bomb (that is stored beneath the cenotaph beside the flame that will burn until all nuclear weapons are abolished.) August 5, the night before, many planes flew over. It was a sleepless night. All of us were dressed in clothes that had been altered from kimonos because kimonos were not suitable for work. All boys were dressed like soldiers. On the morning of the 6th there was an air raid warning but then it was lifted. We were all preparing for the day’s work. I heard the noise of a plane. With my 2 brothers I looked up and saw the shiny planes and thought, ‘oh, planes,’ and then there was an enormous flash; my mother was covered with blood from shattered glass. She took us and fled. In 10 seconds enormous flames came towards us. Those who did not die instantly tried to flee to the outskirts of the city, crying, yelling for help as they headed towards the mountains. Children were crying for their mothers, ‘mother, mother, mother,’ in desperation towards the mountainside. People were badly burned, flesh and bones exposed. What I remember about myself is I was very nauseous and vomited. I saw 2 horses who died with their intestines exposed. People were dying and calling feebly for help, ‘water, water.’ There was a charred four year old but the eyeballs came out and I could not tell if it was a boy or a girl.

Nobody knew what happened.

My family: my 4 years older sister had left home that morning with a cheerful goodbye. She was supposed to be near ground zero. She never came back and the city burned all night and was leveled. When the fires subsided, I saw nothing but wasted remains of buildings and I could see all the way to Ugina port. My mother went out to search for my sister and saw many, many bodies everywhere, including in all the rivers. THE RIVER WAS RED. My mother tried almost 3 months to find her daughter, as far as Ninoshima Island (where some orphans were sent), to find some clues of her daughter, but THERE WAS NO TRACE. After months of searching she became very sick. I think she had a miscarriage. We stayed in a bamboo grove. My brother had burns and maggots bred in his injuries. There was no medicine, no doctors, no way to treat the injuries. THE ONLY WAS POWDER MADE OUT OF HUMAN BONES. Myself, I had bleeding gums around the clock so my mouth was always sticky. My hair fell out. I was tired all the time and had no strength. We did know what it was. People said it was a poison.

One by one people came back to burned ruins. We did not know about Nagasaki. Ten days later Japan surrendered and the war ended. There was a rumor that there would be no plants in Hiroshima for 75 years. We had no hope. Hiroshima—everything was burned. There was nothing in the ruins, nothing to eat. When I first saw the green grass growing alongside the railroad tracks, I thought it was a sign of new life and it gave me relief. THE WHOLE CITY WAS IN CHAOS FOR YEARS.

In the rebuilding process, from the river and earth, many things have been dug out—belt buckles, buttons. Parents who lost children, old parents, rush to see with slight hope if they can find a clue of their children. These parents are in their 80s and 90s now.

July 6—July Glitches

Bark and Leaves from an A-bombed Eucalyptus Tree near Hiroshima castle, 2008

She cannot believe they are leaving in 3 weeks already. She wants another month to make more work because she has run into several obstacles. There are A-bombed objects—split and burned bamboo, a tree knot, a roof tile and others—sitting on x-ray film in light-tight bags in the basement of the Peace Museum where they keep over 19,000 artifacts in a 3 large storage rooms with sliding cedar doors. She finally got a box of medical x-ray film. Unfortunately, she still has found no one to process the film. She and David think that most radiologists and doctors here either do not want to be involved in such an experiment that may indicate higher levels of residual radiation than anyone admits or they don’t want to participate in a failed experiment, “to ruin her work”. She cannot take the film with her because it would no doubt be x-rayed several times on the trip home. The objects have been sitting there for a week. She is supposed to pick the film up tomorrow but she will leave it there until she has a processing place. She is not sure any of it will work. There might not be any exposure at all and even if there is, it COULD be background radiation, radiation from the table the objects are sitting on. It is not a very controlled or scientific experiment. Saying it is “art” seems like a lame explanation.

Several museum workers have family who were “exposed to the A-bomb,” which is how everyone here says it. She finds the language disturbing—that she is once again “exposing” these objects to something. Her son gets very upset every time she says she is going to shoot the trees. He wants her to say, “going to make photographs of the trees.” He is right of course and she has known that ever since she read Susan Sontag’s On Photography in high school. There is an implicit violence to photography, actually and linguistically.

July 15—Ninoshima and Ghosts

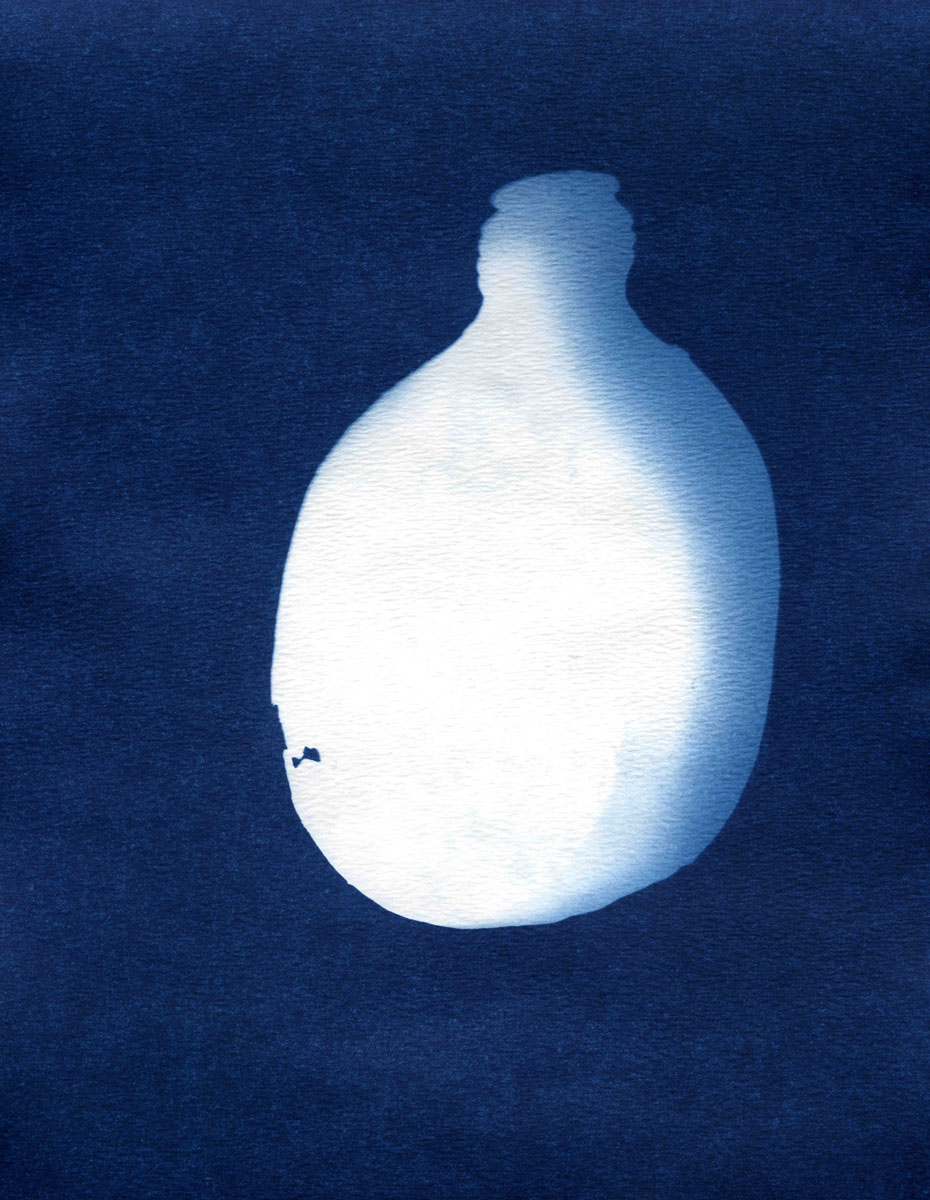

Cyanotypes of a steel fragment and a canteen, A-bombed artifacts from the archive at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, 2008

She is oddly happy with the ghostly white shadows of the ragged aluminum lunch box and round canteen, the slender hair comb and small circular watch face that glow amid the cyanotype blue. Mari, one of the sweetest women in the world, helped her make the prints in the tiny “sunshine garden” of the Peace Museum. She will go back tomorrow to make bigger cyanotypes of fragments of the A-Dome beam, glass bottles, other canteens and lunch boxes, watches. It is an odd happiness because when she places these objects on the paper she feels elated and disturbed simultaneously: so lucky to have access and to be able to make this work she dreamed of making and bothered by the enormous absence that these things mark and hold, aware that once again, here is an American exposing these objects - not to radiation or a bomb this time, but to light in order to render their shapes and being in soft white shadow forms, much like the white shadows cast by people and bridge railings, ladders and plants at the time of the A-bomb. She made a large explosion cyanotype today on her roof using dead flower heads. It looks like stars.

Hiroshima Dead Flowers, 2008

She went to the island of Ninoshima yesterday with Michiko. Ninoshima is 20 minutes by ferry from Hiroshima and it was where soldiers and horses were quarantined during the war and then where bomb orphans were sent after the war. Now there is a boarding school in the same facilities—with old chimneys, military watchtowers and ammunition bunkers close by—for 200 unwanted children. It was beyond hot as they walked around the island to find the horse crematorium, the A-bomb cenotaph, which she did a rubbing of because it said “Comfort Souls” and she doubts she will be given permission to do any rubbings in Peace Park, military foundations and tunnels. (In 2013, she returned to Ninoshima and almost died from over 20 Asian hornet stings. Their nest was inside a military tower that she specifically went back to photograph—on top of a bomb shelter and artillery storage hill. She went into anaphylactic shock and was becoming part of the grassy slope, taking her last breaths when she was rescued by helicopter. The helicopter landed in the playground of the orphanage—now a boarding school for “unwanted children”.)

Playground at the Orphanage built for A-bombed Chidlren, now a boarding school for “unwanted” children, Ninoshima Island, Japan, 2008

Children at the Boarding School on Ninoshima island, Japan, 2008

She was given permission to do rubbings and make photographs in the basement of the old Fuel Hall and City Planning Office—now the Peace Park Rest House. She spent over 2 hours there last week, wearing the required hard hat and sweating profusely as she set up her tripod and 2 different cameras to take pictures of the black rain-like satins on the wall, the worn stairwell banister, the dark and damp room, the rusty door and lonely paper cranes left for Mr. Nomura Eizo, the man who survived at the age of 47 and died in 1982 at the age of 84.

Military Tower on Ninoshima Island, on top of a bomb shelter and artillery storage hill, Japan, 2008

July 28—Her Last Day in Hiroshima

She knows she will be back in Hiroshima some day but today feels like the end of something, thick with finality. She has held back sobs all day. This city has loved her and she loves it back. Hiroshima will never be finished or resolved. It is a constant and eternal place. She could make art here forever.

Circle of Survival, cyanotype of ring of paper cranes, 2013