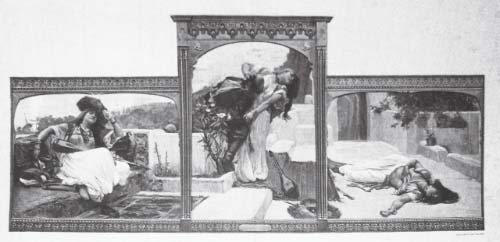

Le Pirate d’amour (1889) is an Orientalist triptych by American Frederick A. Bridgman who, judging by his output, remained as retinal in the painterly pursuit of color in North Africa as the affect depicted suggests. After acquiring a certain «sympathetic knowledge of landscape effects,» he pursued that ‹Other› in Algeria and Egypt, in earnest. Today, I released a musical project entitled Pirate d’amour which bares sinister resemblance – by way of spirited metaphor and concentrated abstraction – to the Symbolism just beneath the Orientalist gloss of F. A. Bridgman’s triptych.

(F. A. Bridgman’s 1889 triptych, Le Pirate d’amour. The right panel is lost.)

With Bridgman’s triptych, we have an ethnographic exoticism suggesting erotic fascination with the Other. An eye finding its muse in a setting sun. A foreign and colorful land, saturated with fantasy, bleeding from the edge of its terraces, gardens, and landscapes. It’s this retreat toward and within the unknown that has rendered the Orientalist gaze open to critique. Edward Said and others have dutifully and critically suggested the conflation of a Western hegemon and its imperialist fantasies1 with an innocent, pre-construction ‘Other’.

But, I respectfully submit that, attendant to that vision, underneath the veneer of the ‘gaze’, is an almost indomitable metaphysical appetite for this ‘Other’, the unknown, quartered and anthologized, after having caught a glimpse. The unknown, as an ontological possibility, instantiates the itch of actualization. The becoming and the attempt to draw an eternally consistent image of the ‘Other’ to achieve both surety and consistency about the object – now subjected, now open to speculation. To be epistemically certain. To be brief with this newly found object, atomized and itemized. A curiously imperfect and incomplete image, hence the more salient parts of Orientalist critique (which, otherwise, might have evinced some methodological inconsistency).

(Left Panel of F.A. Bridgman’s Le Pirate d’amour, 1889)

Today we have the left panel showing exotic relaxation under the predatory gaze of actor/pirate on the verge of destruction – the imminency of his erotic will hiding behind the terrace. This, for me, serves as an abstracted and abbreviated metaphor of the Western Gaze, else the sinister poetry of Orpheus among wolves, else Mallarme’s Faun lost in jungle. Both, conjuring the deep aesthetic flight of an individual, lost in the plume of its condition, as observed – as preyed upon by an outsider, another. The third and final panel is lost to history. It depicted our subject laying oblong in a pool of blood, alone. Dagger at her side. Dagger she absconds with and employs to quit the business of perception, once and for all, taking her own life. Esse is Percipi.2 Preserving what Bridgman referred to (defensively) as her virtue.3

(Middle Panel of F.A. Bridgman’s Le Pirate d’amour, 1889)

Endnotes

1Edward Said, in Orientalism, refers to this as a “coercive framework” that embeds the “private mythologies and obsessions” of Western imperial actors (Colonizers, Scholars, Artists, etc.).

Return to Reference.

2Bishop Berkeley’s (George) famous immaterialist musing.

Return to Reference.

3See The Epoch periodical, where In 1890, after repeated attempts by patrons and press at the Fifth Avenue Galleries in NYC to find Le Pirate d’amour immoral, Bridgman is interviewed and delivers to history this bit of authorial intention: “Why, the picture, I think, shows clearly that the woman saves her virtue at the price of her life.” The Epoch, Vol. VII No. 157 (New York, Feb. 7 - Aug. 1, 1890).

Return to Reference.