We basically hated men, hated being human, hated the world. We talked all the time about the effects of being inhabited by a voyeuristic, masculine eye that made us look at our bodies like a suspicious meat from which we wished to cut away the fat. The eye had a voice and the voice subjected our vulnerable attempts at thought to constant, searing mockery. We called the parasitical subject that occupied and oppressed us IT. We believed IT meant to kill us, literally, probably by suicide.

We lived together in a boarding school in Massachusetts that had a large percentage of students suffering from mild mental illness. Most likely what separated us from other kids our age who were not mentally ill was that our parents had the means to have our depressions, obsessions, compulsions, and utterly destructive episodes diagnosed by psychiatrists who fuelled our ill-ease by naming these ailments.

We used to stay up all night in each other’s rooms, whispering about what we believed and did not believe. We believed in a story about a female deity, or maybe just an entity, called Lilith, who was a companion to God and consorted with all of the animals in Paradise. Maybe also with the plants and trees, maybe with rocks and sand, we didn’t know but we thought it might have been that way.

S’s mother was dating a man who was a screenwriter. None of us had seen any of the movies he’d worked on but S said he appeared to be successful, or at least rich. He had a pool and his house was all odd angles and giant windows looking down over the hills. S said he was nice to her, and very funny, but she thought he was sad like most funny people, and she wasn’t sure but she also thought he might be an alcoholic. One night he had S and her mother over for dinner at his house. He was drinking a lot of champagne, then whisky, and he started to talk about a movie he was working on. It was a long rambling story because he was drunk, S said, but she tried to tell it the way he did.

He used to date an actress, B, who had studied Anthropology in College and who always talked as if that that was her real career that she could return to any time. In the seventies while still in school she’d heard about a film, or not a film really, but a little piece of a film, that had been found in New York state in an abandoned battery factory on the Hudson river. The film was low quality, 8 mm black and white, but nicely shot, and it showed an animal that appeared to be a kind of tiny gorilla but with the head of a blond woman. In the film, which she had never actually seen except for a few stills, the animal could be seen digging in the ground, perhaps burying something or digging something up, or even just digging the way a dog digs, for the sake of it. She could be seen wetting her hands at the bank of a river that might be the Hudson though the angle makes it impossible to know, and she could be seen, from behind, through the trees, combing her hair. Something in the frame causes a light to flash, maybe a mirror, and that is all.

A group of female anthropologists in New York decided to search for the creature and quickly began to act very strange. They became obsessed with their search and left the University, taking the grant money they had received for their studies and using it to supply themselves for a move into the woods in the area where the film was discovered. They broke off relations with their families and never returned to the city except to resupply occasionally. People said they had become a cult but nobody knew what they believed. There was no guru, no man with a beard, no men at all actually. Somehow they survived through selling crafts and pickling summer vegetables. People said they took money to help criminals sneak over the border to Canada or that they sold drugs that came from Afghanistan by way of Soviet Russia and into Canada, and that they brought drugs down as far as the Bronx every few months, but those rumors were unconfirmed and may have just stemmed from the fact that nobody could believe that it was possible to live from knitting ponchos and making pickles. The ponchos and pickles are real and in fact, you can still get them. The women, almost old ladies now, have formed a little company called Opposing Thumbs Craftworks and they have a website that is really just a page with a PO box in Esopus to which you can send a money order in return for a variety of “gifts.” Pickled beets and a beet dyed shawl, pickled onions and an onion skin dyed poncho, pickled cherries and a cherry dyed beret, and so on, very nice things that take four to six weeks to arrive.

Several years after the NYU girls melted into the woods a group of cultural anthropologists from UCLA who were studying feminist separatist activities in the seventies went to New York to study the former students who had become a cult, or something like a cult, and were devoting their lives to tracking or luring the creature who they say calls herself, I, Daughter Of Kong. The UCLA women were powerfully affected by the time they spent in the woods studying the NYU women but they were reluctant to write up any reports, instead they changed the focus of their work. They returned to LA to continue their studies but they also formed a permanent camp in the desert where they spent most of their time doing extremely unconventional research, Inner Sovereign Terrain Research they called it, and it would eventually cause them to lose their funding. B was on the fringes of this group because she knew a couple of the women involved from when she was an undergraduate. She was fascinated by the new research that she referred to as ISTR, which she pronounced like a word that sounded like Ister . She said it changed the field, literally breaking up the ground of anthropology exactly the way an earthquake breaks up the earth, by a movement from inside that you can’t predict until it is too late.

She started to go to the desert camp (she called it “The Compound”) frequently, especially when she was depressed because of a failed audition or a particularly bad role. She was pretty in a way that has traditionally been used to signal endearing stupidity, so she was often cast to appeal to the kind of desire that wants the desired object falling on it’s face or using wrong words or forgetting how a screwdriver works. She wasn’t that dumb in real life and she felt, like so many actresses, that she might never get to experience the full use of her instrument, her self, her body, her voice, her aggression. She used to say, “I want them to SEE me thinking.” or sometimes, “I want them to SEE me thinking about them, about their stupidity.”

When she was depressed by a week spent doing a commercial for cheap perfume or playing the adorable, sexy girl who unwittingly does this or that thing to move a plot along, she would pack up a cooler with fruit and tequila and she’d go to the compound. She’d say, “ I need to break it up.”

He didn’t like how often she went away and he didn’t like the fact he was explicitly not invited to go with her, ever, under any circumstances. He genuinely liked her, even though he admitted (to himself not to her of course) that the impression she gave of being airy and hapless was part of her appeal, he also liked her because she was a little angry, a little unpredictable and he even felt that made her acting more interesting than people gave her credit for.

One evening when he was drunk she came to his house straight from one of her trips out to The Compound excited to talk about a “process” they had done in which they made contact with I, Daughter Of Kong by going inside themselves, whatever that meant. He saw how excited she was and he wanted her to be that excited about him. He suggested that they work on a screenplay together about this creature that she’d just contacted. She could play I, Daughter Of Kong, he said, he could make that happen, he said. And she would be able to use everything she knew about acting. She would put her body beyond language in the service of the role but it would also be important to show the effects on the animal of the human head, the little pretty blond starlet head that rode atop the animal like an imperious queen in a hairy carriage. He said they would make a film that showed her thinking. Thought would emit from her silently, it would kind of pour from her body like light and water, only invisibly, but they would also write really amazing smart dialogue that would show friendship between women.

B was excited by the idea of writing with him and especially of playing the role of I, Daughter of Kong. She started trying to get into the role and sometimes he would wake up in the night to the sounds of her moving animalistically about the house in the dark. She would often bump into things because she felt that she should practice leaping around at night without artificial light. She ate only raw, vegetarian food and spent most her time at home naked or in a fur vest if it was chilly.

The first period of writing was wonderful for both of them. They spent whole weekends drinking wine and writing together, letting themselves commit the most wild and serious thoughts to paper. When the time approached for him to meet with a producer, he looked at what they had done and he knew that it didn’t stand a chance of even being read by an intern. It was too weird, too feminist, it had no plot, no sex, too many scenes that were in all close-ups with no dialogue or action; B slowly chewing on a fern, looking right into the camera, B rubbing her face against the trunk of a tree with her eyes closed, B weeping to the sounds of the original King Kong movie....He quickly came up with a pitch that wouldn’t make him seem insane. He figured the whole thing would be considered a bad idea, which happens to everyone, but that it didn’t need to destroy his reputation.

The day came that he met with an important producer whose name he wouldn’t say. Very interesting, the producer said, I could see this being a great movie. There was some work to be done on the script the producer said. Of course he said, and he went home to B to tell her the good news. During the weeks that followed he had several meetings with people to work out the kinks, as they put it. Each meeting changed the script a little more. What was wanted was something that would be a love story but also a horror movie with a supernatural element. Something like Altered States but not so pretentious.

He told himself that B would accept the changes because she’d be happy that the film was getting this far, that she must know how hard it actually was to sell a script and that she had probably always realized that the writing of it was more about the two of them spending time together than it was about real life goals. He told himself that at the end of the day everyone in town was compromised, that even the producers probably felt that way. Maybe they had all come to Hollywood wanting to bring Brecht to the screen. The thing he put out of his mind was the question of casting. Of course he had no control over casting. He could say a name and it might momentarily graze the consciousness of someone who mattered and then later surface in their thoughts as an unattributed occurrence. That was the best he could hope for. When the day came to meet again with the very important producer whose name he would not say, the producer reported that the utterly transformed script was good, and he wanted to make the film, and he even wanted the screenwriter’s input. The producer said he thought it could be a success that would make a name for the screenwriter, that he could be like Paddy Chayefsky, a name that can stand alone. It was at this point that B’s name was floated into the air. The producer looked quizzical, then remembered who she was, sort of, and nodded absently. I was thinking of someone a little scary, the producer said, like Theresa Russell.

At that point he sort of wished the script had been rejected outright because it was suddenly clear to him that B was going to be crushed. Maybe she’ll understand he thought, after all, she knows what this business is like, but he doubted it. Her airy, hapless quality was not entirely a surface event but came from a real lack of understanding of how the world works, not only that but an unwillingness to understand, the same unwillingness that made her spend weekends at The Compound rather than going to parties to meet people who might help her career.

The script that the producer liked was something like this: There’s a vain, ambitious scientist in an inconspicuous laboratory job who dreams of being famous. He hears about a piece of film that shows a part ape, part human female and sets out to track her in the woods. From the trees, she watches his bungling attempts at camping out, first with amusement and then with compassion. One night, as he is sleeping, a mountain lion approaches his sleeping bag. The ape woman leaps down from a tree, grabs the scientist and swings him back up into the tree with her. The lion grazes her leg with its claws and she bleeds on the scientist waking him up. The scientist thanks her and from that day on they develop a rapport. She is lonely and he is helpless in the woods. He charms her with promises of love and she feeds and protects him. They build traps together and they make ropes from plant fibers. Eventually, he convinces her to come with him to civilization. She says, How could I trust any human after what happened to my father, King Kong? But, like any human woman, when it comes to love she is a pure idiot.

As soon as they get to NYC he shoots her with a tranquilizer gun and throws her into a cage. His plan is to bring her to the laboratory and to do tests on her. Her strange genetic makeup will allow him to make breakthroughs that would be impossible for his contemporaries. The next part of the movie is basically torture and horror under bright lights in cold, clinical settings surrounded by beeping and blinking machines, the opposite of the Eden like, romantic scenes of the forest at the beginning of the film.

One night there is a substitute janitor on duty in the building where the lab is. She has not received the instruction, DO NOT GO INTO LABORATORY 12 FOR ANY REASON so she enters the lab with her broom and bucket and as she’s emptying a wastebasket she hears a weak voice say, “help me.” The substitute janitor is shocked when she finds the caged ape woman with a beautiful, tear stained, human face. She puts her hand out and the ape woman puts her hand out and they wordlessly wind their fingers together in complete understanding of what is to be female and to suffer. The janitor simply releases the ape woman into the night. As they stand at the door to the building the janitor says, “Do you have a name?” and the ape-woman says, “I, Daughter Of Kong.”

Then we see the ape woman tracking the scientist. She scales the side of his apartment building and watches him through the window. She watches him go to sleep. She follows him to work in the morning and watches as he emerges from the building agitated and enraged and gradually, terrified. She calls him from a payphone, “I’m watching you.” She breaks into his apartment when he’s not home and shreds his bed with a knife, she steals his cat, she covers the entire bathroom mirror with red lipstick. It’s very creepy and we almost start to feel sorry for the scientist. The scientist starts to come unhinged. He screams out his window into the night, “Come and GET Me! Show Yourself!” She leaves a note that says meet me at the Paris Hotel in Queens, room 616.

He goes to meet her, tranquilizer gun in hand, but this time she is ready. He walks in the door and she drops down on him from the ceiling, grabs the gun, gets the scientist in a headlock and drags him out the window, up the outer wall of the building and onto the roof. There she ties him to the neon Eiffel Tower and shoots him with the tranquilizer gun. He is paralyzed but not unconscious as she makes her final speech about the horrible nature of man, about the perils of love and about her father. She calls on her father for vengeance and a great image of King Kong appears in the sky wreathed by lightning. Lighting hits the neon Eiffel Tower and the scientist is charred to blackened lump. The ape-woman runs off into the night laughing.

The screenwriter had to admit that Theresa Russell really was perfect for the role.

By this time in his story S’s mother had gone to bed and the screenwriter was losing steam, staring absently into his glass.

So, what happened? S asked.

The film is in pre-production now, he said.

No, what happened to B?

She left me. She shredded my mattress with a knife, she covered my bathroom mirror with red lipstick and she stole my cat.

Where did she go?

I don’t know…The Compound probably.

You didn’t go looking for your cat?

No…she never told me where The Compound was and anyway, she really loved that cat and the cat loved her. It was probably better.

Do you miss her?

B or the cat?

I don’t know, both.

Yeah I guess, but to tell you the truth I think I care more about the film now.

And my mother?

Her too.

So that’s it, S said to us…She’s out there somewhere.

—Cynthia Mitchell for I Daughter of Kong

[scroll left to right]

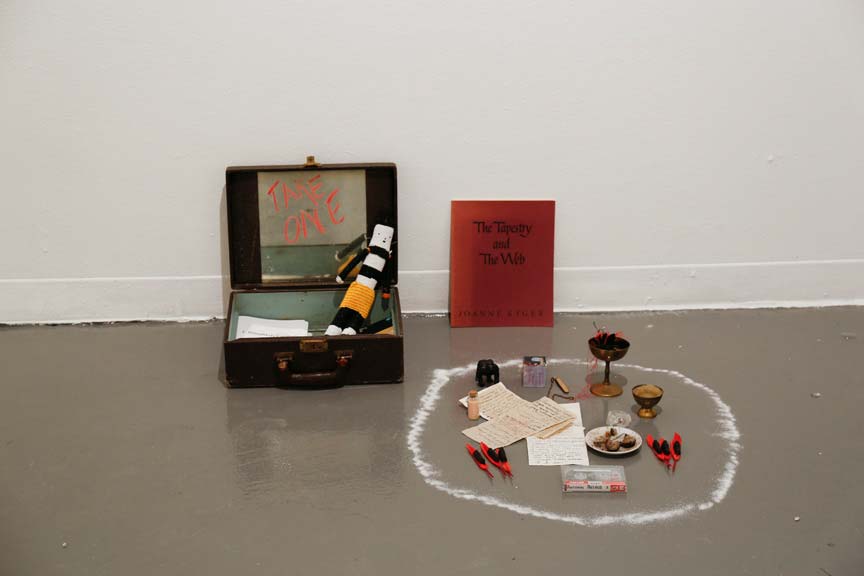

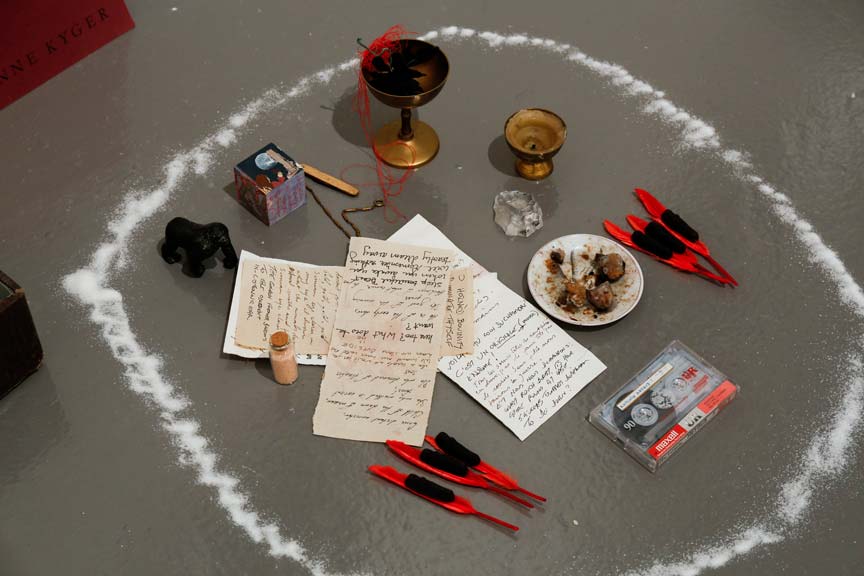

I, Daughter of Kong Center for Research

Jeffery Moser for I, Daughter of Kong Center for Research