There is a papaya tree growing in an abandoned apartment in a narrow alley in Tainan, the oldest city in Taiwan. The tree’s bright green leaves look like coats of arms, and rise and fall and flap like they are going to lift the tree, but the thin straight trunk, growing through a crack in the blue and white tile, does not move. The papayas are also bright green. When typhoons pass, the undersides flush dark. They look asleep, or more likely thinking, like eggs or breasts or genitalia.

Three friends (the poets Dot Devota, Lynn Xu, and Josh Edwards) and I took the train north to Tainan from Kaohsiung, where we were living together (June/July 2014). We had been walking (wandering) the narrow streets of Tainan for many hours when we turned into the narrow alleyway, passed the abandoned apartment, glimpsed the papaya tree, walked a few steps, then paused. A memory was already forming. Did someone, or something, say something (or someone)? Did the tree in that alcove say something, have eyes? We turned around and entered the abandoned apartment through its open metal door, saw the tree, the bushes and weeds growing also through the tile. Abandoned is not the right word. The apartment had been removed. Like a piece of cake. There was no roof, cement walls on both sides, narrow sky.

The tree was two or three or four years tall. There was a family in the alley: an old man, a middle–aged woman, and a young girl in a stroller. The young girl was a hawk, while the woman (the young girl’s mother?) and the man (her grandfather?) seemed mostly disinterested, yet with the incisive disinterest of provisional lords.

The bushes and weeds growing through the blue and white tile possessed a hybrid character, like they had been fertilized with soda. The papaya tree possessed a simple, yet inexpressible power, evacuating the energies of those who once lived there by incorporating them into its solemn, ingenuous body. Suddenly the tree was like the stake at the base of which the ashes of ghosts had cooled. The spirits that remained were interlopers from the city, and became, about the tree, prototypical and shy. There were no insects, no butterflies. The sun shined high on the walls. Eggs, breasts, genitalia—or a virgin, a mother, one color removed from a rainbow, uncoiling in an empty room.

Other ruins: the old neighborhood where KMT soldiers used to live (near the naval base) on the western edge of Kaohsiung. The walls had been torn down. The ruins could not enclose more than a few dispersed sparks, caught on the frayed power lines. A guard in a metallic helmet holding a machine gun standing motionless on a small white pedestal looked manufactured, inhuman. His blood was metal. His talent for appearing to be all knowing was wasted.

Two black dogs emerged from the trees lining the edge of the old neighborhood. They looked like they were going to say something to us—a warning, at first, then a modest salutation—then changed their minds, sinking into the leaves. In an attempt to prevent the old neighborhood from being demolished, people covered the walls with graffiti. But this was another afternoon; the graffiti had been demolished.

I think of Taiwan as a mound, or a fruit bound in an impassive, unimpressionable skin. A beetle, or a funerary amulet—like a scarab, or an island small enough to fit inside a corpse.

There were black dogs also on the southern end of the mountain separating Kaohsiung from the Taiwan Strait. That was the day we went to find the hotel where a friend’s mother had died. The friend was a poet. Her mother, whom none of us had met, was a storyteller. She had been staying in a hotel on a beach on the southern end of a mountain where thousands of rock monkeys lived. She was, at the time of her death, working on a story called Monkey King. She had been working on it for many years, and had not yet finished.

We crossed an old stone bridge carpeted with red pollen to get there. Black dogs stared at us from the gorge below. Light penetrated the bridge, dryly igniting a swallowing sound.

Dear dear Brandon,

My mother loved Kaosiung so much. I would like to go there. To see what she loved. To see where she died. To see the Seasbay hotel where she stayed. To meet Jasper who was there with her in the hospital. Who was with her again at the very end. And her friends who took her ashes and bones and put them in the urn. From what I understand she had become a sort of minor celebrity there or at least was quite loved by a group of groupies. She was in very good health there for the most part and really, really happy. To be honest I didn't share her enthusiasm for the story of Monkey King. I never liked hearing her tell it. The photos I downloaded from her little camera of Kaosiung—it all seems very unreal, very unlike her. A world so far away from my domestic existence in NYC that it feels like not on this planet with me.

I'm afraid to go there. Afraid something bad will happen to me because she is still so angry with me. But I also feel like I need to go there.

Yours,

Rachel

Rachel ...

How did your mother manage to accumulate groupies in Kaohsiung? Or, was this common wherever she went? Did she have good friends there? If so, are they still there?

You should come to Kaohsiung when we're there! Though it's soon: June, July. You'd have our support. You could stay with us. We could talk you through it ...

Well, that's when we are there, but it's probably not the ideal time to go, weather-wise. It's hot, humid, infernal. But it must be confronted. When we're not teaching, we're walking. Eating. Sitting beneath an air conditioner. Drinking. Eating. Visiting temples. Going to the mall. Taking notes. There are monkeys in the hills. Thousands. They will dance on your head. People slow-dance in the park. Old women. It's coming back into view.

There's a festival every summer dedicated to a poet who committed suicide by drowning himself in a river. People threw food in the river to keep the fish away from his corpse. I'm sure the fish ate his corpse anyway ...

Brandon

Rachel ...

Writing from some unintelligible hour here in Kaohsiung … I wanted to write because you and your mom have been on my mind. You mentioned your mom was at the Seas Bay Hotel? Do you know where that is? Is it in the city? I'm just curious ... I don't know what I mean by any of it, and I hope you don't mind me asking ...

From afar,

Brandon

Dear Brandon,

Are you still there? I wish in a way I'd gone this summer!

I have serious wanderlust.

Here is where my mom stayed:

Diane Wolkstein

Seasbay Hotel

5l Lianhai Rd.

Kaohsiung 80441

TaiwanI would so like to go there some day. If you ever go by there ask about her. There was a guy who worked there named Jasper with whom she was very close. Other people too.

xoxo,

R

Dear Rachel ...

Thank you for the Seasbay Hotel. I know where it is! Not far from the ferry to Cijin Island. Near the university. On the coast. Enormous trees with long air roots and hanging vines, not far from the mountain where thousands of monkeys live.

I think we're going to go there tomorrow (Thursday). It's not far from a shrine. We'll ask for Jasper. I don't know what we'll say to him, but that we know the daughter of Diane Wolkstein ...

Brandon

Rachel ...

We went to Seas Bay. Jasper wasn't there. But Leo was: the young concierge. He knew your mother. Do you want to hear about it? The place, the view, Leo's recollections? I'll send a longer description, if so.

Brandon

Oh oh. Oh. I absolutely want to hear anything you want to tell me. It means so so much that you went there and saw it with your own eyes. I have such complicated feelings about it and want so much to go there and am also afraid. It seems impossible. Seems like another dimension entirely.

xoxo,

R

Rachel ...

I've waited until the verge of falling asleep. Feels like the right time to attempt a description. Though, I wish we could meet for ice cream or lemonade or summer street food (somewhere) …

I hope I'm not too incoherent:

The four of us (Dot, Lynn, Josh, and I) went to Seas Bay. We took the long way: subway (to the end of the line), back streets and narrow alleyways to an overgrown (weedy, pollen-dusted) stone staircase into the trees, up the mountain, past an abandoned badminton court, a cave being guarded by a pack of wild dogs and an enormous black spider, over a half-eroded stone bridge, around a shrine built during Japan's occupation, along a winding road that descended through a parking lot of a thousand motorbikes, onto the university campus ... Seas Bay is right next to the campus: Sun Yat–Sen, between a mountain and the ocean: enormous buildings and enormous trees with millions of air roots hanging low to the ground …

Seas Bay is at the southern end of campus, alone. We were nervous. We stood outside staring at the glass door. Menu stand in front. We read the menu. Beer. We went in. A young man was at the front desk: Leo. I asked for Jasper, but Jasper was off. I felt dejected. The lobby is narrow, but airy, with large windows facing onto a patio facing onto the beach facing onto the ocean (etc). Huge ships in the ocean. I don't know what kind: container ships? They looked like battleships: big and black, with the sun behind them (it was late afternoon by the time we got there). We sat on the patio beneath a thatched umbrella and ordered beers. There were dozens of people on the beach, and a few families on the patio. A lot of young families, young kids. One white guy: European. Came up to us and said, Did you notice the Christmas decorations? (We didn't see any Christmas decorations). Then said, They keep them up all year long, but ... they don't mean anything! Then he walked away.

I said a few words about your mom, then we raised our beers to her. We were there for two hours. Talked about our parents, storytelling, and death.

The sun was setting behind the black ships. It’s the western edge of Kaohsiung, and is mountainous: tall, precipitous mountains. No evidence that there is a city on the other side of the mountains.

I went back in the lobby to talk with the young man behind the front desk. I asked if he knew a woman named Diane Wolkstein who stayed at the hotel not too long ago, and he said Yes. Right away. I said, I’m friends with her daughter. And he said, I know. (!). He called his manager on the phone, but his manager was busy. Apparently the manager knew your mother much better. So, it was just Leo. He gave me his card. I asked what he remembered about your mother. He said: she was up every morning by 6 o’clock doing tai-chi or yoga on the grass beneath the palm trees, facing the ocean. And: she told stories. He didn't specify where or what stories. I stood at the front desk with Leo, then looked out the large windows onto the patio where Dot, Lynn and Josh, were sitting and drinking. I was sad that neither Jasper nor the manager were there, but that they weren't felt OK, right, like: you're asking too much!

We sat on the steps outside the front door for a little while before continuing our walk. Walking back towards the tunnel through the mountain, we came upon a pile of ceramic yellow ducks embedded in a small piece of dirt beneath a tree: dozens of yellow ducks, like rubber ducks, but ceramic, with big black eyes. I tried to pick one up but they were cemented into the dirt.

It was a privilege. A pilgrimage … we felt grateful. It was a feeling, more so than anything we could articulate. That your mother was a storyteller felt important. That you are a poet felt important. That we are poets felt important. Clearly, with Leo, on behalf of the people we didn't have the luck to meet, your mother was immediate. The mountain separating Seas Bay from Kaohsiung is called Shoushan. Better known as Monkey Mountain. Where the Seas Bay is is the tail-end of Monkey Mountain ...

Brandon

I did not hear back.

At the end of the rainbow was a dead mother, and her daughter was waiting.

The enormous black spider was a small, obsidian sun. Each dog was an incarnation of the dog below it on the slope, forming a progression of dogs, culminating with all the dogs reappearing together where the woods gave way to a road. The mountain was filled with spirits—the dogs, the spider, even the pollen was animated. The bridge was steep, separating. Afternoon light on the rock walls is yellow in memory, then clear and gray and dark blue and brown. Is there a temperature in dreams? The humidity had dissipated, and a light wind was only a suggestion of shade.

The dogs were staring from the leaves. We were being watched. And when the dogs disappeared, the feeling intensified. We were walking towards an image, it surrounded us: the dead mother, the storyteller, manifesting in the eyes of the dogs, watching us advance up the mountain, over the mountain, the dogs’ eyes, in turn, manifesting the future for the solar obsidian.

The first time I ate papaya I was standing in a river. I do not remember the river or the people, but a papaya being passed around like a joint. I took it—it tasted like coffee. Spanish moss hung from the thin branches of tall gray trees. The world in that moment was held at a strange, vertiginous angle. But when I think about papaya, I do not think of the fruit, I think of the tree. The taste is subsumed into a shape, a disposition. The tree is an irreducible mother who loves but does not live for her children.

As if prefatory to the unfinished story that dawns every morning in the storyteller’s absence, I picture a woman on the beach. I picture her on the grass beneath palm trees, facing the ocean. Everything the mother experienced was a resource for a story she was telling or going to tell. That is why she was alive. The story she was telling or going to tell brought her to life, each time, each experience adding to the ongoing ellipses.

She woke up before six—she was there on the grass by six—to exercise her body into letters.

She died in the winter.

At the end of the alley where the papaya tree was growing, right before the alley opened onto a busy four-lane road, was a windowsill. The windowsill was to the left of a door. The door was short and white and very inviting, like a grandmother’s door. The window was dark. The lights were off or everyone was asleep or no one was home. On the windowsill was a three-dimensional Chinese character:

I do not know what it was made of—foam or thick paper or plastic. It had the personality of a small animal, stuffed, like an owl. We paused in front of it. Lynn—the only one of the four us who could read the character—asked us to guess what it was. We each guessed something practical and, given what evidence we had of the door, unlikely—like psychiatrist or hotel. As if the red character could only be announcing what was inside, rather than sharing a thought with whomever passed.

Spring, Lynn said.

The moment itself had a caption, a name, in the character for Spring.

The papaya tree is blue in the evening. Spring is either the alley’s final, punctuating word, or, depending on which end of the alley you enter, its overture. I hear and see it at once—a petrified orphan, placed on a windowsill, cracking.

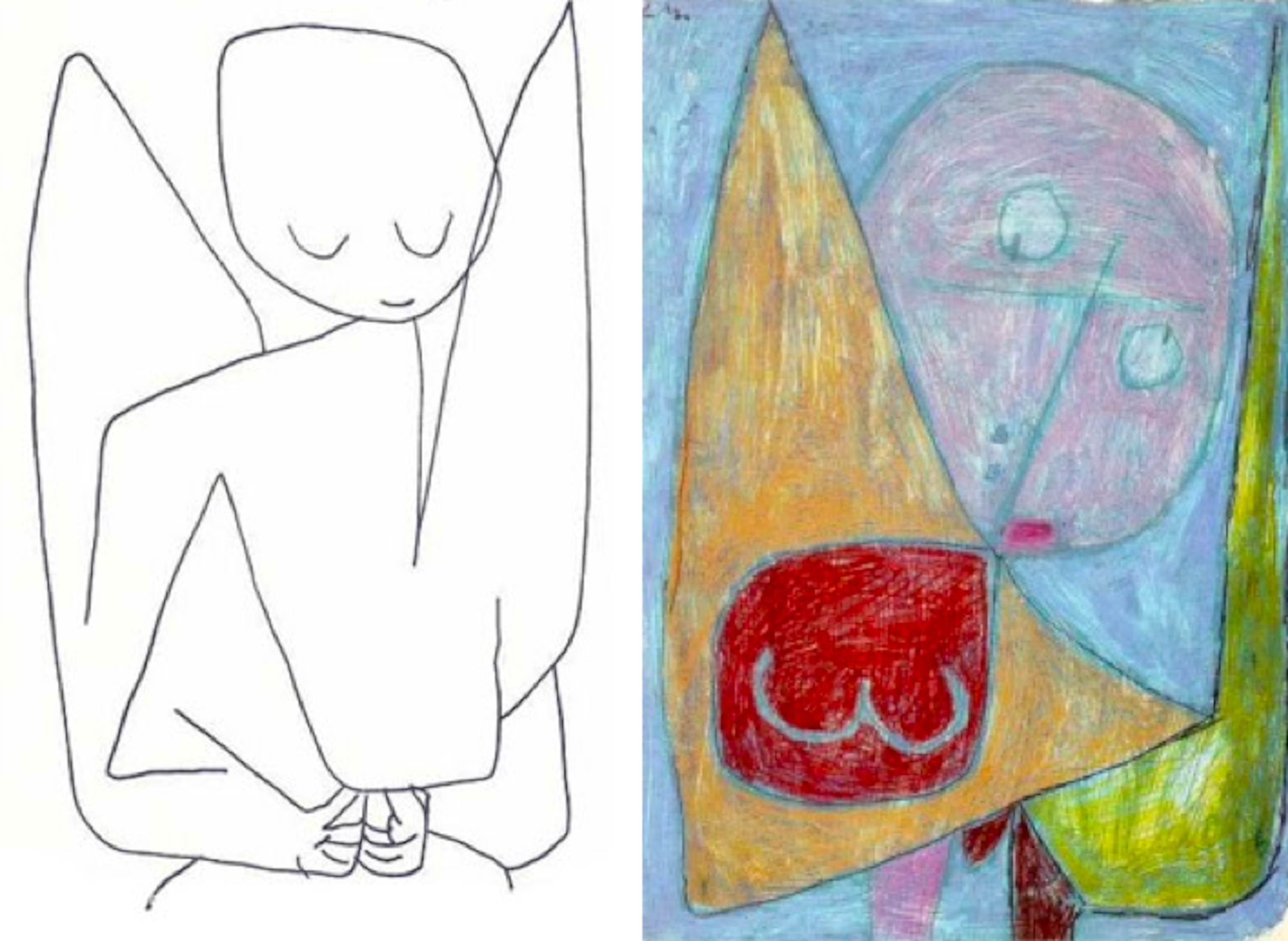

NOTES: The black and white photographs included in this essay were taken by Joshua Edwards on opposite ends of Shoushan, aka Monkey Mountain, in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, July 2014, and are included in his collection of photographs, Formosa, available at castlesislands.com/formosa. Also included are two images by Paul Klee, both from 1939: Forgetful Angel and Angel Still Female. Lastly, I did hear back … Thank you to Rachel Zucker for allowing me to share our correspondence. Thank you also to Rachel for—not only responding to my description of our pilgrimage to where her mother died, and to this essay, about which she had many feelings, and many things to say, but for sharing with us the story, and the location, of her mother’s last days.