In 1990s Cape Town, in the interregnum after the fall of apartheid, the poet Sandile Dikeni created “Monday Blues,” the city’s first desegregated reading series, at Café Camissa on Kloof Street. Sandile, who had trained himself to write in his head while under detention without trial, read his poems— “telegraphs to the sky,” he called them—from memory. Perhaps it was here the urban legend emerged: “Camissa,” we thought, meant “place of sweet waters” in the indigenous Khoe language. And the waters the urban legend speaks of have run from Table Mountain to the sea, under the city itself, since before the colonial Dutch ships. An untrammeled toponym, from before the 1652 arrival of the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), “Camissa” became a wellspring for the cultural reclamation I witnessed in newly democratic Cape Town. In the 2000s, Café Camissa shut down to make way for a real estate agency—a symptom. Ubi sunt, Sandile?

Turns out “Camissa,” as if El Dorado, was a linguistic error: Colonists likely mistook the Khoe words for water, freshwater, to mean an actual place. Still, the springs and streams exist—I have gone down into tunnels on the mountainside, waded in the underground water, surfaced from a manhole almost at the sea. And the echo of its promise, of the nascent city it names into being, haunts me—on the double album Dream State, the jazz composer Kyle Shepherd recorded the track “Xamissa.” Its X stands for, in part, the multiple ways in the intersecting languages of Cape Town, past and present—Khoe, |Xam, Afrikaans, Xhosa—the first consonant may be said.

“Place is question,” Timothy Morton writes. In that sense, my poetry book Xamissa emerged from its title. The question Xamissa raised: Was the version of the sea-mountain city where I was born and grew up—with its history of colonial dispossession, enslavement, apartheid—simply inevitable, or could there have been another city, a just city, an open city? If so, which people—in the archives, in the memories of Sandile, friends, myself—almost brought that city into being?

To see this question through, I became—or am becoming—a relational poet. While the poetics of Xamissa owes much to Muriel Rukeyser’s extension of the document, to Charles Olson’s graphicity, and to the radical parataxis of the Objectivists, it is ultimately Édouard Glissant’s The Poetics of Relation that became its grounding influence. Drawing on the metonym of the rhizome—in the same genus as Ishmael Reed’s “Jes Grew” in Mumbo Jumbo—that is, “an enmeshed root system, a network spreading either in the ground or in the air, with no predatory rootstock taking over permanently,” Glissant writes further that “rhizomatic thought is the principle behind what I call the Poetics of Relation, in which each and every identity is extended through a relationship with the Other.” In that spirit, while searching the crowd, the archive, and choral memory for its sources, Xamissa investigates the relation of multiple languages, sociality, and resistance in Cape Town in its bid to interrogate the archive as a draft of the city’s future.

Rhizomatic to postcolonial thinkers such as Steve Biko and Frantz Fanon, Glissant’s archipelagic position on the Caribbean island of Martinique became a necessary counterpoint for Xamissa to the land-locked discourse of my 1980s education, which the apartheid government called, euphemistically, Christian Nationalism. “Sediment then begins first with the country in which your drama takes shape,” Glissant writes. “The landscape of your word is the world’s landscape. But its frontier is open.” Glissant’s open frontier became an invitation to reframe South Africa, to look at the country in which my drama took shape at a closer scale. What if, Glissant asks implicitly, the writer looked to the ground (sediment) instead of the heavens (transcendence)? In other words, rather than nostalgia for “Camissa” as an idealized version of pre-apartheid, pre-colonial Cape Town—the romantic equivalent of transcendence—what if writing Xamissa were to enact the passage of archival water with its forking, deltaic tendencies? What if Xamissa were to try to speak of the sediments or evidence, however fleeting, transported by this archival water?

“Begin and begin again,” Gertrude Stein writes, a statement of poetics and its enactment. My way of beginning Xamissa again and again became to ask questions. One of the questions that I returned to: Is this an act of isolation, of my poem above all else, or is this an act toward an our, even if of no more than an imagined us? At the upper limit, the sociality Fred Moten sings of?

Before I began Xamissa, I often used to sit down to write, in order to write nothing. I used to sit and not write. In my head, in the way, the isolation of growing up under apartheid, and also in the way the (male, colonial) myth: The poet, to be a poet, must be alone. Alone and somewhat mad. The male poet must cultivate isolation, in order to procure (via self-inflicted social wounds) “genius.” This fallacy is a misreading of the Romantics, a misreading of John Clare especially, but it is a misreading that has become a cultural headstone that encourages an early death.

Questioning the lyric prevalence of “I”—the “I” of the poem, its relation to others, its subject position—helped move this “I”: not exactly out of the poem but out of the way, out of the way of the writing. And to insist that the “I” be at the center of a long poem on Cape Town would have re-inscribed the centrality and privilege I had been granted in the city by the apartheid state at birth. The speaker needed to speak at the edge of things. Once I began a praxis, through the help of many teachers, of poetry as a way of art toward others, toward the “human circle” (Kafka’s phrase), toward being with and among others, I began again to sit down and write Xamissa.

Lyn Hejinian’s question then became crucial to beginning again: “Who is speaking?” I am white, male, South African, complicit. On the page, Xamissa attempted to situate its speaker, a version of myself, through the documentary inclusion at the beginning of the book of my apartheid-era birth certificate, as an instance of owning up to a history over which I had little choice, and in the reflexivity of the book’s central movement, a 65-page serial poem titled “helena | Lena | ᨙᨒᨊ.”

This serial poem begins in the Cape Town archive of the VOC, also known as the Dutch East India Company, whose annual profit of 2 million guilders in the 18th century depended on slavery. Its counterpart, the Dutch West India Company, colonized Manhattan. “By 1660, all the major language groups of the world . . . were represented in the windswept peninsula near the southernmost tip of Africa,” writes Robert Shell. For most, the polyglossia of early Cape Town was involuntary. The VOC had colonized the Cape to set up a way station on its shipping route between Amsterdam and the Indian Ocean territories it had seized. Mercantile antagonism between the Dutch West India Company in the Americas and the Dutch East India Company meant that it funded slavery largely in the Indian Ocean Basin. From 1652 to 1808, the Dutch East India Company, as well as its Dutch, German, French, and English settlers, imported 63,000 enslaved people to the Cape, largely from India, Indonesia, Madagascar, and Mozambique.

Chartered in 1602, to monopolize the spice trade, the VOC was the world’s first publicly traded company, a foreshadowing of the stock exchange. Likewise, its monogram—the intertwined letters V, O, and C—became the precursor of corporate logos. This recurrent logo marks the first colonial structure at the center of the city of my birth: The VOC Lodge held up to 1,000 people and, until 1828, remained the “largest single slave holding”—an urban plantation—at the Cape.

At the threshold to the archive in the serial poem, I situated myself—the speaker—as a metaphoric former employee of the VOC, to acknowledge my subject position as a white South African, a beneficiary, who both grew up under apartheid and came of age after. In many ways, the reflexivity that writing on the archive—of a company synonymous with slavery—called for became both a method of composition and an invitation to the reader. As Ruth Jennison writes:

[T]he poet fashions … materials in the interests of fostering such historical subjectivity, and in doing so develops an aesthetics that points up individual subjects’ embeddedness in collective and social histories. Objectivist reflexivity enjoins readers to situate themselves in relation to these histories, and to imagine themselves as potentially revolutionary agents of transformation.

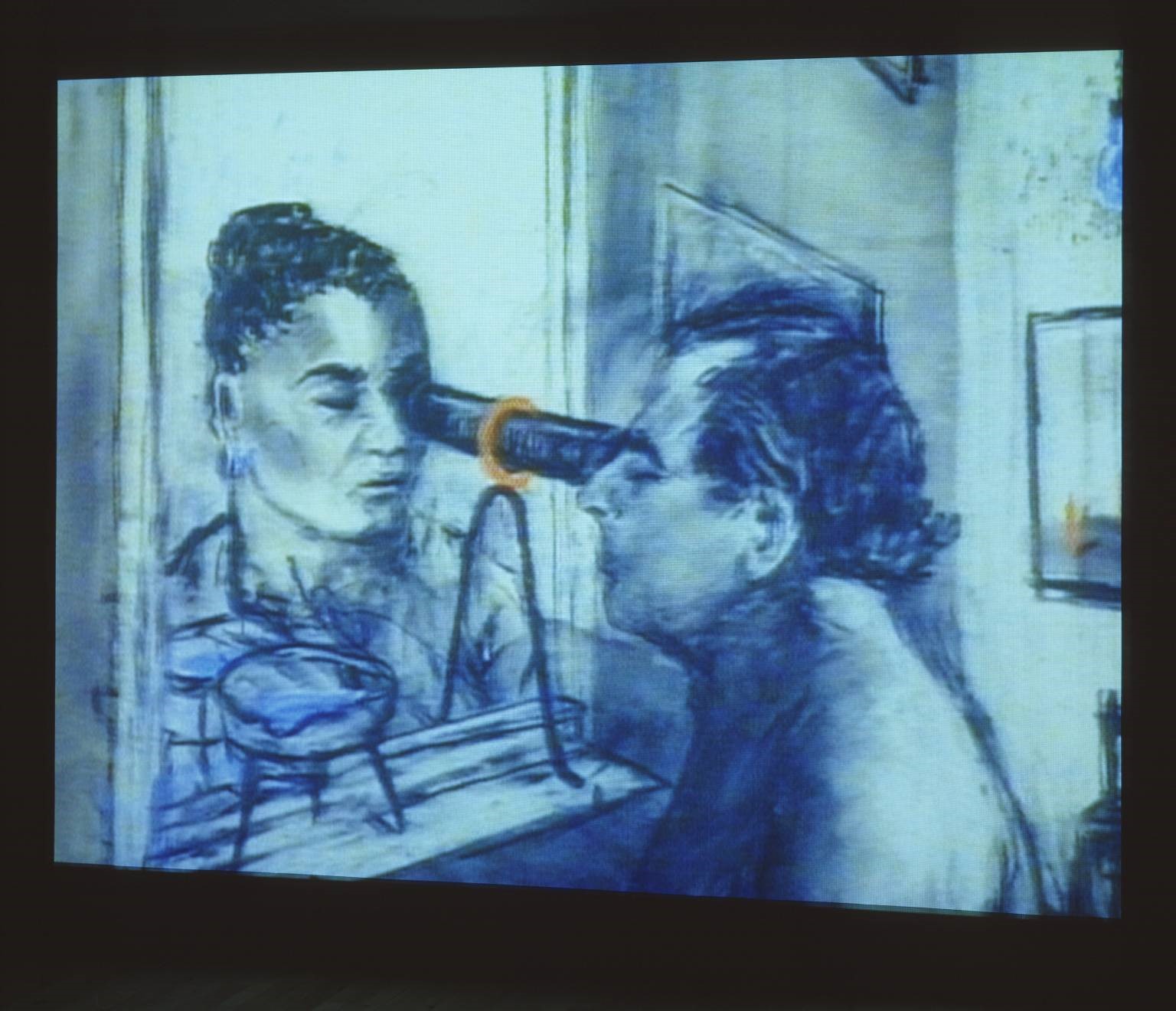

The equivalent in the visual arts of this “Objectivist reflexivity” would be William Kentridge, also South African. Kentridge has been an influence much of my life. He often includes his own (white) hand in his charcoal stop-frame animations, a reflexive move, an enactment of Glissant’s poetics of relation. In a key scene from his animation Felix in Exile, for instance, which I saw in the 1990s, the titular figure, Felix—Kentridge’s alter-ego perhaps, represented as white—sees and is seen by the figure of Nandi, a woman of color. In the frame below from Felix in Exile, the way that the two figures see each other, the mirrored telescope, is double-ended. At first glance, the self-reflexive mirror (or window?) suggests an equality of power between Felix and Nandi:

Looking back at this frame now, there’s a relational naiveté to Felix in Exile, released in 1994, the first year of democracy in South Africa, and not enough engagement with what Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda articulate as “the racial imaginary.” Rankine and Loffreda write:

One way to know you’re in the presence of—in possession of, possessed by—a racial imaginary is to see if the boundaries of one’s imaginative sympathy line up, again and again, with the lines drawn by power. If the imaginative sympathy of a white writer, for example, shuts off at the edge of whiteness. This is not to say that the only solution would be to extend the imagination into other identities, that the white writer to be antiracist must write from the point of view of characters of color. It’s to say that a white writer’s work could also think about, expose, that racial dynamic. That what white artists might do is not imaginatively inhabit the other because that is their right as artists, but instead embody and examine the interior landscape that wishes to speak of rights, that wishes to move freely and unbounded across time, space, and lines of power, that wishes to inhabit whomever it chooses. Or that wishes to absent from view whomever it chooses.

In an alternate reading of the Felix in Exile frame above, instead of a telescopic equality between two subjectivities, it’s possible that Felix, in trying to see and be seen by Nandi, only sees a mirror projection of himself—and this representation serves as Kentridge’s warning against the solipsism of whiteness, of the racial imaginary. This mirror image is further suggested by the fact that Felix’s left-eye is closed and Nandi’s right eye is closed. Still, as later frames in Felix in Exile depict, through the double-ended telescope Nandi and Felix only see each other’s eye. In this moment, all they see is seeing. Is seeing the precursor to speech, Hannah Arendt’s synonym for political action? Either way, Felix in Exile—and, in its wake, Xamissa—takes some initial steps toward a reflexive acknowledgement, if not a true examination, of the racial imaginary.

By way of Glissant’s “accumulation of sediments,” a grounded, disillusioned approach to the lyric, rooted in the documentary, Xamissa’s sediments revealed in cross-section my racial imaginary: Across the threshold of the archive, the serial poem “helena | Lena | ᨙᨒᨊ” offers a fragment, in Dutch, from a 1727 VOC document tallying its possessions at the Cape. By reading against the grain of the document’s intent, the serial poem suggests that a woman of color named “helena van de Caab,” or Lena, without precedent in her lifetime, marooned from the urban plantation of the VOC Lodge to join an alternative city—“Polis is this,” Charles Olson says—in the mountains above Cape Town, and that 14 women and men, soon after, echoed her action.

Unlike the figure of Nandi, in Felix in Exile, the figure of Lena is not invented but emerges from archival documents, the same VOC records that codify her enslavement. Is sediment more than mud? Despite Xamissa’s leitmotiv of water, it is really the archival mud—of the VOC inventory in 1727, among other documents—that animates the serial poem. Xamissa re-describes the 1727 document as evidence of insurrection. Through a forking narrative path, in which alternate versions of Lena’s resistance overlap with further soundings of my subject position, Xamissa invokes the social space that she begins, the city in which Lena herself is at the center.

To that end, in a series of addresses to this central figure, or to her silence, the poem “helena | Lena | ᨙᨒᨊ” asks questions that remain answered: How to ask Lena’s permission to address her when her permission cannot be granted? How to investigate the authorial impulse to represent Lena’s marronage, her flight from enslavement, yet ensure that it does not re-inscribe her violent experience at the hands of the VOC? Are these questions, sounded out in Xamissa, ethical in spirit or is any representation of her marronage, by definition, a poetic failure? If so, how can this failure clarify white privilege—the limits of the imagination Rankine and Loffreda speak of?

“Perhaps a way to expand those limits,” Rankine and Loffreda write, “is not only to write from the perspective of a racial other but instead to inhabit, as intensely as possible, the moment in which the imagination’s sympathy encounters its limit. To see what that shows you that you have not seen.” Is the word “question” the opposite of “transcendence”? The poet has to be on the ground, acknowledging limits, in order to ask questions. In the same spirit, Roberto Bolaño says: “the word ‘writing’ is the exact opposite of the word ‘waiting’.” For me, writing Xamissa—enacting its questions—became the opposite of waiting: for utopia, for certainty, for transcendence. Xamissa’s interrogation of its materials, without transcending its racial imaginary, attempted to expose its lyric habits, ground its imagination, and gradually expand its limits.

In serial increments, or what Rachel Blau DuPlessis calls “segmentivity,” Xamissa traces Lena’s marronage into the mountains above the city, juxtaposed with alternative versions of events, glimpses of the present, interruptions from post-colonial thinkers, and interrogation of the poem’s racial imaginary. One such interrogation is embodied through the proxy figure of an 18th century functionary, anonymous in the archive, whom I name and imagine as a potential ancestor, Pieter Fourie. He is a proxy not only for whiteness but also for the act of writing: the clerk behind the ornate handwriting of the 1727 document that attempts to itemize Lena on paper.

The VOC kept track of enslaved people in far greater detail than its employees—likewise, no equivalent document lists the many burghers in 1727 upon whom the slave trade depended. In the handwriting of Pieter Fourie, who inventoried all the names of enslaved people at the Lodge and noted Lena’s absence, I recognized by implication my own hand in the document. I named the functionary after my grandfather, who had a government job reserved for whites, as a proxy both for myself and for my Huguenot ancestors, French immigrants eager to benefit from slavery.

The representations of Lena van de Caab and of Pieter Fourie in Xamissa stem from opposite ways of reading the archive. As the historian Nigel Worden clarifies, reading against the grain of the archive can be seen as “extracting from archival traces material that was not intended by its creators but is nonetheless evident ‘between the lines’ as well as hunting outside the archive for what has been forgotten or suppressed.” Evidence of Lena’s insurrection was not the corporate intention of the VOC’s 1727 inventory, even if reading the evidence as insurrection is also a misreading of the historical Helena van de Caab’s intentions, itself an act of the racial imaginary.

In Anna Laura Stoler’s Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense, “on the nature of colonial documents from the nineteenth-century Netherlands Indies,” Stoler argues for the value of reading along the archival grain, that is, of reading with the “paper castles” of whiteness in mind. (“Paper castles” stems from Steve Biko’s critique of apartheid-era documents). As Worden explains, reading along the archival grain entails “seeing how the form and structure of the documents both reflected and shaped power structures and decision processes.” The figure of Pieter Fourie then articulates in Xamissa, in a self-reflexive way, the power structures and decision processes in the VOC archive that I benefited from as a white poet.

While Xamissa stops short of depicting Lena’s interiority, and does not describe her physically in any way, its serial addresses to Lena do flesh out her action. I mean “action” in the way Hannah Arendt means “action,” that is, political action. The incremental montage of “helena | Lena | ᨙᨒᨊ” circles around a historical moment in Cape Town when the resistance Lena joins, in the mountains above the city, almost topples the colonial order—the VOC’s grip on the peninsula—by setting the city on fire, a cipher for freedom.

In a sense, Xamissa addresses Lena’s creativity. Its series of questions suggest that Lena creates the possibility of action, not only for herself but for the citizens who follow her unexpected newness, her natality. As Arendt writes, “the new beginning inherent in birth can make itself felt in the world only because the newcomer possesses the capacity of beginning something anew, that is, of acting.” Xamissa does not—indeed, cannot—claim transcendent autonomy on behalf of the historical person, Helena van de Caab, whose enslavement was actual. Still, in the same way that the 1727 VOC inventory reveals, against its corporate intent, the fact of Lena’s marronage, court records also document the fact of her presence among the Hanglip maroon community in the mountains above Cape Town. Xamissa reads this evidence from the archive against the grain to suggest that Lena’s action culminated in her creating a precedent, a new path, for being among others, in the polis of their choosing, its citizens named at the poem’s end.

Xamissa falls short, though, on the grounds of Arendt’s equating “action” with speech. The poem cannot offer Lena’s speech—her words do not exist in the VOC archive—nor does the poem speak for her, other than a gesture indicating silence. Could the poem have imagined, on Lena’s behalf, her resistant speech, her critique of Xamissa? Through its questions, the poem suggests Lena’s critique but does not imagine it in her words. Rather than speak for her, Xamissa tries to re-remember Lena’s marronage—her action—which became the groundwork for her potential speech in the maroon community, speech that Xamissa does not and should not have access to.

In a paper in Nature titled “Remembering the Past to Imagine the Future: the Prospective Brain,” neuroscientists Schacter, Addis, and Buckner claim that the imperfection of memory—the fact that recall is not a literal replay nor is it exact—underlines “[a] function of memory that has been largely overlooked,” namely “its role in allowing individuals to imagine possible future events.” So as to “imagine non-existent events and simulate future happenings,” the brain recombines and re-imagines information stored in memory, rather than relying on a perfect, cinematic recall. “This suggests that the simulation of future episodes draws on relational processes that flexibly recombine details from past events into novel scenarios,” Schacter, Addis, and Buckner write. In other words, the malleability of the past—memory’s potential—opens alternatives for the future.

The archive in Xamissa echoes the prospective function of memory. As the narrator of Chris Marker’s film Sans Soleil states, “My pal Hayao Yamaneko has found a solution: if the images of the present don't change, then change the images of the past.” Simply put, Lena’s action “should not be forgotten,” as the epigraph I included from the Sureq Galigo states. By acknowledging the limits of representation, dictated by the archive and by my racial imaginary, the imperfections of Xamissa’s recall suggest, nevertheless, the potential impact of Lena’s action for future citizens. Lena’s precedent—her natality—is the point of remembering her action, now re-imagined in Xamissa as the prospective archive. By recombining and re-imagining the available evidence on Lena’s political action hidden in the archive, Xamissa simulates future action and invites readers, in their own vita activa, to imagine and act toward novel outcomes.

In financial dire straits, the VOC became defunct in 1799 after the short-lived Batavian Republic nationalized its assets. Great Britain took over the Dutch colonies, including the Cape, in the Napoleonic Wars, by which time the moral bankruptcy of the VOC and the person-owning society it fostered had laid the groundwork for apartheid. The Hanglip maroon community lasted until emancipation in 1834—when someone chiseled A PERSON FREED into Table Mountain, on the pathless route that Lena would likely have taken more than one hundred years earlier.