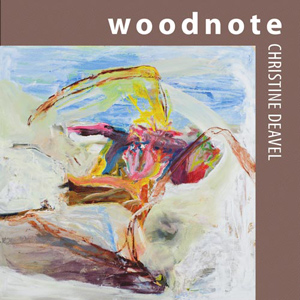

First Book Questionnaire: Christine Deavel | July 20, 2012.

1. Does your manuscript bear any relation to a graduate thesis project?

Only in as much as my name is on both of them. The person attached to that name is different as well, so that is as it should be, I guess.

2. How do you feel about these poems now that they’ve materialized in book format?

I still like them, which is a relief. That’s not to say I don’t see awkwardnesses in them; I do, but I can live with those. And I’m still learning about the poems and their relation to each other. I didn’t fully understand I’d written a book until I had one.

3. What was your experience when you began publishing? What challenges did you encounter?

When I was a young MFA student and then recent graduate I had a few acceptances in literary magazines, which was encouraging. Over the years (I graduated from Iowa in 1982), I had occasional journal publications, though I didn’t send out work with much frequency. Editorial responses when I sent out a book manuscript were less encouraging — in fact, rather discouraging. A little over a year ago, I was considering the possibility that I might not ever find a home for a manuscript, that I might not ever have a book.

4. How, if at all, did chapbooks prepare you for the making of a full-length collection?

I had one chapbook of some size and one that was tiny, and they both were culled from a manuscript rather than preceding one. I’m not sure what I drew from those experiences; I think it was subtle. Perhaps I began sensing more what voices went together. I do think the chapbooks prepared me a bit for the experience of having a reader, a person who comes to the work on her or his own and chooses to buy the object that contains it — and sometimes then shares an opinion or thoughts. That’s an experience unlike one I experienced in workshops and is still rather novel for me. And often quite lovely.

5. How did you shape and order your manuscript?

With trepidation, confusion, and assistance. Of course, because the manuscript consists of several longer pieces, there wasn’t much to monkey with. At the very last minute, I did follow a suggestion to pull one poem out of a series and place it at the end of the book, something I would never have thought of because I couldn’t see the series in any other way.

6. Was anyone or anything indispensable in the process of making your debut collection?

Yes, indeed. From the long list I will mention my publisher, Beth Spencer, who through her generous and careful attention to the manuscript made me really start to see it for what it was and could be; my husband, J.W. Marshall, steadfast and inspiring as poet and partner; and a number of people who invited me to participate in various projects. Several of the pieces in the book were written as the result of an invitation. I am deeply grateful for community.

7. What is your impression of book contests?

I would prefer they weren’t used. Particularly when they are blind and have rotating judges. There’s a disincentive to use the traditional and useful methods of publishing — recommendations to editors by teachers, colleagues, friends, acquaintances. It strikes me as counterproductive that writers and editors must fight against the very relationships that are the foundation of their community or deny their skill at discerning and fostering good writing. If a contest is not blind and the press’s editors are making the decisions, I’m not so troubled by it. That’s more like an open reading period with a fee. No fee would be ideal, but I understand that would be a challenge for many small presses. Guest judging of contests can make a press’s selections seem arbitrary. When a press makes it selections solely from contests decided by outside judges, I feel I can’t really get a handle on the press itself, its editorial vision.

8. How did you learn to navigate the press world?

I was greatly assisted by my profession — bookselling. I spend my days surrounded by poetry books from presses tiny to huge that I have had a hand in ordering and in selling (or not selling).

9. What aspirations did you have for this book?

I primarily just wanted it to exist and sit beside other books on a shelf. The pieces in it are in some ways a conversation with others’ poems, and I think I wanted that relationship to be visible. When I write this, I realize that I have always envisioned my book on a bookstore’s shelf, in proximity to the books it’s calling out to. I never see it alone.

10. How would you describe this work?

A haunting. By me of places that matter to me, and of me by those places and the people who walked there.

11. Do you work primarily on discrete poems, serially, toward a project, with a set of concerns, or otherwise?

I usually sit down to see what I’m thinking. Often (at least the last several years) that’s meant a serial piece is the result. I visit and revisit something.

12. Whose poems affect you or your work?

I cannot possibly list them all here — and I may not even recognize them all — but I can unabashedly say Anne Carson, Lorine Niedecker, Allen Grossman, Jean Valentine, Theodore Roethke, C.D. Wright, James Schuyler, Fernando Pessoa, Ippekiro, Ian Hamilton Finlay.

13. What are you working on now?

I’m working on working on something. I’m slow and somewhat apprehensive about writing. I keep talking myself into it. At the moment, I’m sort of listening for a voice, jotting down messages sent and received, and reading C.G. Jung’s Memories, Dreams, Reflections.