First Book Questionnaire: Michelle Taransky | January 4, 2013.

1. Does your manuscript bear any relation to a graduate thesis project?

Barn Burned, Then, the book is similar to the graduate thesis I wrote while working towards my MFA at the Iowa Writers Workshop. The time between thesis drop and manuscript submission was, I think, less than a few months. The difference between the thesis and the book are slight, but, for me, make the book project distinct from the thesis: the book does not contain a six-poem series of univocal lipograms, and the book cuts some of the less-developed characters and narratives thanks to Dara Wier’s excellent readings and suggestions during a magical meeting in Amherst, MA during the Juniper Institute.

2. How do you feel about these poems now that they’ve materialized in book format?

Like the role of the author is legitimated for most by the emergence of the “book” product, the act of holding the book in my hands did make me “feel” like a poet who had “written” a “book,” though those foundations were completed prior to the promise of—and independent of the need for—objecthood.

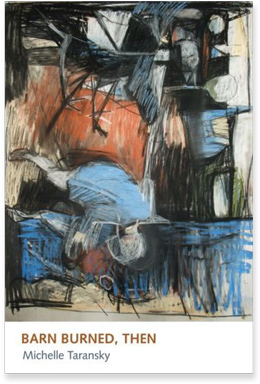

Among the good feelings upon publication: using an image by my father, artist Richard Taransky, on the cover of the book. My father and I are in continual dialogue with each other’s projects. Many of my writing ideas come from his drawings and what I “see” within them. My dad began the drawing on the cover after an Iowa to New Jersey conversation about the emerging characters and landscapes in my poems. My dad overlaid the ideas of Barn Burned, Then with Brugel's “Blind Leading The Blind.”

3. What was your experience when you began publishing? What challenges did you encounter?

In high school we often wrote creative and critical work that was compulsorily submitted to competitions. Knowing those works would gain readers beyond my local teachers, classmates, parents, and friends was motivating, made me feel an out-of-body kind of thrill—and, still, that possibility of new readers remains the most attractive component of publishing.

4. How, if at all, did chapbooks prepare you for the making of a full-length collection?

In the middle of writing Barn Burned, Then (right at the moment when bank replaced barn), I started to work on “The Plans Caution,” a collaborative chapbook in dialogue with my dad's unbuilt architectural work, commissioned by Andrew Rippeon from QUEUE books.

Andrew’s work as an editor is caring, generous and smart. I know both my father and I agree that Andrew, through the hand of the press, became a kind of third collaborator, pushing the work to unexpected points of inquiry, understanding and confluence.

5. How did you shape and order your manuscript?

Because the process of writing the poems was and is inseparable from the process by which I discovered what these poems were about, and the story of the barn and the bank, the teller, the robber and the gypsy, the order of the manuscript remained (mostly) in the order in which the poems were written. Thanks are due to Robert Hass for his advocacy and support of this method during a meeting over the manuscript.

6. Was anyone or anything indispensable in the process of making your debut collection?

Friends who listened to plans, drafts and revisions. Readers in workshops who were variously energized, made uncomfortable or annoyed by the obsession with barn and bank. And my dad for reminding me of the best way to deal with the anxieties of making work: “to put your head down and make more work.”

7. What is your impression of book contests?

Like most institutions, there are myths and truths. I’d say: well, it’s a business. And I’d say, too, well, it’s not a business. I am thankful to the book contest—in particular, of course, Omnidawn’s contest, as it was through that process that I came to know publishers Rusty Morrison and Ken Keegan, whom I have been lucky to also work with on my second book.

Rusty is the most generous and the most engaged reader I could have hoped to find in any universe, and am glad the universe of book contests introduced us.

8. How did you learn to navigate the press world?

It’s been more of an I “do” learn to navigate, as in, I am still learning to navigate—and I am doing this by navigating.

9. What aspirations did you have for this book?

Discovery, invention, surprise, a reader, then readers. And then, to talk to the readers. And to read their work, too. Doing interviews like this one, participating in the ongoing dialogue about [first] books and what poems have done and may do in the future.

10. How would you describe this work?

Depending on the audience: 1. poems about a family’s barn burning down, and the family building a bank on that site. 2. lyric poems 3. a story 4. an aftermath 5. an event, as well as events 6. corrupted lyric poems 7. stutters and misunderstandings

11. Do you work primarily on discrete poems, serially, toward a project, with a set of concerns, or otherwise?

All of those. As a poet, I am not unlike a child with many craft projects at many stages of completion. I work on many surfaces and places and like to write in noisy environments with many starts and stops.

12. Whose poems affect you or your work?

George Oppen, Louis Zukofsky, Charles Reznikoff, Robert Creeley, Muriel Rukeyser, William Carlos Williams, Susan Howe, Charles Bernstein, Bob Perelman, Rachel Blau Duplessis, CAConrad, Emily Pettit, Dara Wier, Guy Pettit, Jordan Stempleman, Caryl Pagel, Meg Barboza, Ben Kopel, Natalie Lyalin, Josh Bolton, Travis MacDonald, JenMarie MacDonald, Srikanth Reddy, Dan Beachy-Quick, Elizabeth Robinson, Rusty Morrison...I could go on!

Being in contact with poets who are working hard, and my students who are writing and reading hard, continues to affect me greatly. I am excited to be writing among and amidst so many others who are engaging in the disruptive business and practices of poetry.

13. What are you working on now?

I’ve just finished work on my second book, Sorry Was In The Woods, which will be out during Spring of 2013 from Omnidawn.

And I’m in progress on three other projects: 1) “work projects” a conceptual aggregation, started January 1, 2012 in which I record each time I hear, or read, or say “work” by writing down the two words that proceeded and the two that followed “work.” Other rules have developed as the days pass and the work suggests them. 2) “Ephraim Goldberg”: poems thinking about naming and name changes, organized around famous Jews who changed their names to “sound less Jewish,” and also forced name changes. 3) a book of essays exploring alternative models to the traditional creative writing workshop.