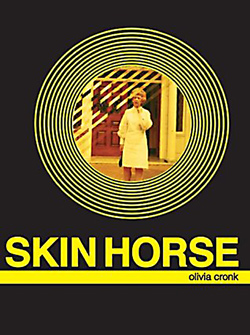

First Book Questionnaire: Olivia Cronk | October 12, 2012.

1. Does your manuscript bear any relation to a graduate thesis project?

It does so in a looking-through-the-fog kind of way or in the narrative of pursuit proposed by the velvet-luscious Velda (Maxine Cooper) in Kiss Me Deadly: first a string, then a thread, then a rope. None of the poems had their current bodies or selves when I completed my MFA thesis, but the writing I did for that was, of course, writing for Skin Horse—and none of the new text can exist without the process of peering through the lace of the old text: seeing my mistakes, growing bored, consuming new art while learning more about its production, stealing new tricks, avoiding the physical part of writing while allowing the lazy ideas to pile up untended to, reorganizing computer files, submitting things, getting accepted and rejected, talking with my husband—who is my primary reader—about pieces and wholes, and waiting around quite a bit for my brain to make progress.

As another response, though, I think that I was just beginning to form a poetics of my own as I finished grad school, and that is the misshapen skeleton of the work I did and do.

And, finally, a third response: No: my thesis project was eight years ago; that’s a long, long time in growth of ideas. I tire of my writing too quickly to preserve pieces for that long.

2. How do you feel about these poems now that they’ve materialized in book format?

Strange.

The physical presence makes the poems feel done, though I write, quite often, in a re-churning of old things . . . so it feels funny somehow that I might/might not return to those bits of language for new material.

Some of the poems in there are no longer interesting to me; I cringe a little. I assume that everyone does this.

Some of the poems in there are still pleasing to me, are what I want to do, to be able to do.

Some of the poems feel like some other I whom I knew but cannot really conceive of anymore.

3. What was your experience when you began publishing? What challenges did you encounter?

I assume you mean the logistics, the process of making the work public. I got both acceptances and rejections at a somewhat steady rate. I never took any of it, in either pile, very seriously. I saw the process as a necessary painstaking for being/becoming a published poet. I understood that publications would lead to more publications, that my work might become somewhat validated by this process, that maybe a manuscript would eventually be accepted, that such an event might mean that I could/can write more books, and that all of this has practical ramifications for my writing/teaching life and also that much of the process (the need for self-promotion inherent in a submission, the insider/outsider tinge of it, etc.) is vile.

4. How, if at all, did chapbooks prepare you for the making of a full-length collection?

I tend to write (and do all my different kinds of projects) in serial form. I usually have a bundle of poems that are from the same process or of the same ilk. And then I tend to wind up with groups of these bundles. I have telegram poems and poems to be performed/read aloud and poems that were part of an attempt to create new slang and poems that respond to Blake and poems that do not use the second pronoun and, currently, poems that correspond with a series of spookalicious photographs my husband took of our apartment one stormy night when I was pregnant and the lights seemed to flicker over our literal and figurative domestic messes.

Years ago, I turned my collection of poems to be read aloud into an e-chapbook called Gazooly. Thankfully, my first submission of it (to Beard of Bees) was accepted. That underscored for me the importance of small coherent collections. A couple years after that, I staged some of the poems in a theater festival . . . and then, after that, I felt that I was really done with the collection. It had served its purpose for me. I am not so interested in the same ideas anymore, but I am glad that the chapbook still exists. I suppose that experience helped me think about a group of poems as a body of its own. I have never felt that my poems were strong enough to stand alone; they work most effectively, I think, in the context of a collection, framed by other trinkets of sense and sound. I like that one poem might leave an aftertaste when the page is turned to the next.

I also handmade ten copies of a chapbook for Andrea Rexilius’s old press, Parcel (now, or soon to be, Marcel). In that case, I semi-randomly chose poems to exist together in a collection. That process certainly prepared me for organizing what ultimately became my final manuscript, though none of the poems are in both places, at least not in the same form.

5. How did you shape and order your manuscript?

I really love this kind of process—arranging things in a kind of collage. It is the same pleasure I feel when setting a table for a party or fiddling at a table after a party. But most of the ordering and arranging that I like so much is ephemeral, so I found this process a little stressful. The permanence of it is threatening.

First, I sequenced the poems in a way that suggested a loose line or narrative or movement through mood, and then my husband looked at it with me/for me and made suggestions—all of which I followed, and then my editors, Johannes Göransson and Joyelle McSweeney, suggested a few opening rearrangements—and in doing so, revealed to me a new context for the rearranged poems, and then it was done.

6. Was anyone or anything indispensable in the process of making your debut collection?

My husband, poet Philip Sorenson, is my intellectual partner in all ways.

7. What is your impression of book contests?

I think that book contests are useful and sometimes messy.

8. How did you learn to navigate the press world?

I learned by a winning combination of attempt, shame, internet searching, and reading contemporary poetry books.

9. What aspirations did you have for this book?

I wanted someone to read my book in her/his home—in a tub, maybe, or in bed—or on a bus . . . maybe in a motel room. So far, I have had several reports of my success in this aspiration.

10. How would you describe this work?

Mood-poems: a spilled open junk drawer with small fancy mirrors and sticky edges from hard candy, sucking cough drops while staring at a squirrel corpse stuck to the sidewalk, watching your grandma draw her eyebrows in/on, dead skin and cheap violet bubble bath, a dress-hem coming unstitched and getting noticed after a few cocktails in the early spring in a bar playing 70s Marianne Faithfull.

11. Do you work primarily on discrete poems, serially, toward a project, with a set of concerns, or otherwise?

I work almost exclusively in serial form. If I write a discrete poem, I immediately look to see how it will fit into my current project/series.

12. Whose poems affect you or your work?

Though this is in no way a comprehensive list, I have been previously affected/infected by the poems of: Mei-mei Bersenbrugge, Alice Notley, Bhanu Kapil, John Donne, Lara Glenum, Hiromi Ito, Sandra Doller, John Keats, Martha Ronk, and of course all my friends and people with whom I have somehow “worked” (like Rexilius, Sorenson, Göransson, McSweeney—all mentioned in various ways above). I can never ever recover from the pleasure of “Prufrock.” I read it over and over.

13. What are you reading now?

I am reading Don Mee Choi’s translation of Kim Hyesoon’s Princess Abandoned, Rexilius’s Half of What They Carried Flew Away, some articles on cinema for a film course I am co-teaching (a feminist critique of Brian De Palma’s use of the male gaze and an examination of cinema as a postmodernist act), some bits and pieces of things (short stories, fragments of things from Harper’s), and my English 102 students’ research proposals.

14. What are you working on now?

I am writing the series I mentioned above: poems that respond to some pictures my husband took. They are (poems and photographs) grotesque corners, domestic disgust, the safe spookiness of the unclean, basement decay; I am combining my ideas about the pictures with some ideas about space, probably psychedelia, and definitely ritual. The collection might be called taupe house.