Reviewed April 20, 2012 by Peter O'Leary.

A description at the front of this book informs us that kintsugi is the Japanese practice of repairing ceramics with gold-laced lacquer to highlight the breakage. Seven poems of varying length (the longest, eighteen pages; the shortest, one) follow. These lines come from the opening of the first poem, a sequence called “Forty-Eight Pieces”:

And then a page later:

Kintsugi is the book Meyer wrote in the shadow of the death of Jonathan Williams, poet and founder of the Jargon Society, who was Meyer’s companion for nearly forty years. It’s a book of great gentleness inscribed in a plain language whose lyrical intensities gather into a cumulus of feeling analogous to the metaphor the title provides for us: a breakage – of a lifetime’s habits and thinking – is illuminated by strokes of language that lash forward into the unknown. We feel these cracks in Meyer’s poem as a series of associations and gestures, for which “Jumped,” in the second stanza above, is exemplary. A jolt, yes. But for what? As the book progresses, Meyer intensifies this feeling of brokenness by way of the simple, incredibly effective technique of inserting periods between phrases and even words, staggering a reader’s progress through these lines. From “Endings”:

Time thickens in the pauses. And then moves on. These poems have unbearable weight felt as a transient shifting, like a mover carrying something very heavy, losing his balance, and then suddenly finding it again. In the course of these seven poems, one perception immediately leads to the next. We don’t know yet where it will lead but we trust we’ll know more as we move through the poems. Kintsugi is a profoundly moving book, written with the skill of a master. But it’s also a profound book, one in which poetic technique repeatedly reveals depth of feeling for its subject and ranging insight about the ways poetry accepts and rejects mourning. History isn’t more than this.

That Meyer is not more widely or enthusiastically read is one of the repeated petty crimes that make up life in the poetry world of contemporary America. Oh, well. No biggie. It’s a topic Meyer himself has addressed with characteristic insight and care in an essay published anonymously at first and then posted to the Jargon Society website for anyone to see who might care: “On Being Neglected.” In that essay, Meyer writes:

A moment of clarity but the question is how to act on it. Meyer’s decision to accept neglect stems from what he observed among the poets around him. He writes about a conversation with an acquaintance who had just received a major award, including recognition and money, but who continued to insist he felt he was being neglected and misunderstood. When does it end? Meyer notes:

Most poets don’t have the presence or equanimity to imagine their work in these terms. But the truth is that most of us, including today’s winners of prizes and gatherers of laurels, are writing poetry that will be forgotten in time, sooner likelier than later. Meyer’s decision to avoid the tinsel of poetry glamour and not to hustle for attention has afforded him obvious freedoms, some of them clearly represented in the ranging work he and Williams accomplished over the years with the Jargon Society, publishing the works of poets, photographers, and other eccentrics in sumptuous editions, vitally recovering the work of hidden masters (importantly Loy and Niedecker), and keeping Meyer’s own work in print. Meyer has described the work of Jargon as advocacy. More to the point of the work at hand, Meyer’s commitment to poetry and his devotion to the explorations of the lyrical vectors Modernism and the New American poetry originated have permitted him to write unstained by the anxiety of fleeting trends. Few poets have revealed as many of the possibilities and perfected more of the actualities envisioned by Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro” and magnified in the subsequent vortices of Imagism, the Objectivists, Projective Verse, and Black Mountain poetry as Meyer. His body of work, gorgeously assembled and published in At Dusk Iridescent by the Jargon Society in 1999, is replete with examples of Greek lyric ecstasy, Poundian para-translation, troubadour sonneteering, and consistently rewarding sonorousness. Three examples, for instance:

Meyer is a poet of impeccable musical skills and visionary incisiveness; through his work, you can trace a clear line from Jonathan Williams through Bunting to Pound and back of Pound to the Pre-Raphaelites, to the Provencal poets and Dante, and to the Romans, the Greeks, and the Chinese in antiquity.

I have the fantasy that the history of poetry in the twentieth century could be limned with the tool of non-sequitur and not much else. Surrealism and Dada, of course, but also Modernist cubism, the film-like editing of the Objectivists, projectivist collage, and the stream-of-consciousness of the New York School and its associated institutes, for starters. It’s a technique of nearly inexhaustible application, to gauge from much contemporary poetry, and like many an overused thing, it has enabled lots of unpleasant and boring diffusion. What was exciting in the hands of Stein or Breton or Pound has become tedious in much of the work of the present. As a technique, non-sequitur has depended typically on the strength or quality of the elements being associated by sequence: red wheelbarrow; rainwater; white chickens. What has been explored with less attention is the notion that non-sequitur represents a quality of perception itself and that, furthermore, that quality is not only capable of being represented in language but it’s a feature inhering in language itself. I’m thinking about Meyer’s use of periods in Kintsugi, of course. But this book isn’t his first involvement with this technique. Rather, it has informed his work for a few decades.

I first noticed it in 1999 when At Dusk Iridescent was published and I read Meyer’s poem “Rilke,” which begins:

This is Rilke’s first “Duino Elegy” made new through the application of periods. Building tension in the phrases, tuning in to potential repetitions, Meyer finds the core of the original, releasing energy with each new phrase. (The poem goes on to shift to the “Sixth Elegy” halfway through, a gesture in Modernist translation Pound validated in “Homage to Sextus Propertius,” making a whole poem out of parts of vigorously translated others.) Meyer applies this technique to other translations found in this collection: a poem of Trakl’s, the end of Faust Part II, Goethe’s Venetian Epigrams, some Stefan Georg variations, fragments from the fifth book of The Odyssey, a Celan translation. And then also to observation more simply, finding clarity. “An Equation” runs: “The yellow air and earthly ox. / Unmade and grazing in the sun. // A knife, a block of olive wood.”

In 2003, Skanky Possum published a chapbook of Meyer’s, Coromandel, a sequence made up of five long poems. (Though technically a chapbook, it’s really as long as a full-length collection.) It’s Meyer’s first full-length exploration and application of the period, availing the novelty of expression he discovered in rendering translations with this technique to consciousness itself. The first poem in the collection, “Part II,” includes these lines fairly early on:

In these couplets, Meyer permits each thought arising to unwind, giving it verbal presence. But he doesn’t resist the shifts each thought brings. Sunset to subset, for instance. In “This Is the House,” the punctuation and abruptness intensify:

From this seemingly limiting mode of expression, Meyer coaxes impressive flexibility. New thoughts act like verbs; full sentences receive rewarding complements after completion. And there’s a feeling of movement that pervades. The appearance of Pindar in this selection is notable. Pindar’s odes have exerted a lasting presence in Meyer’s poetry, especially with their mix of praise, mythology, and implicit moralizing. Pindar’s name appears, perhaps, as a mental reminder of these tendencies. Or perhaps even as a kind of verb; an imperative, at least. Most impressive to me are these poems’ lightness. Last year, a friend sent me a recording of Meyer reading this book, which I listened to very early one February morning driving from Chicago to Louisville through the dawn into the day. Meyer has an understated but mesmerizing reading voice. Matched to the hypnotic accumulation of words and phrases in these poems and to the repetitive progress of driving, it was an otherworldly experience. I felt as though I were inside Meyer’s lyric mind.

But this hypnotic entrancement involves a heaviness, too. Back to Kintsugi, consider these lines from “Last Poem” (which is not the last poem in the book):

Notice here the way Meyer attenuates the sequence of perceptions with syntactically complex sentences—the first one about desire, the second about the rhapsodic—stitched together so cunningly it might take a few readings to get the syntax straight. The barking dogs that open the book have returned. And there’s the question punctuated with a period. Pindar returns, occupying a holding place similar to the one in the poem from Coromandel. Pindar wasn’t a poet of mourning but grief was a topic he addressed in his odes. In “Olympian II,” alluding to Oedipus, Pindar writes, “But diverse are the currents that at divers times come upon men, either with joys or with toils. Even thus Fate, which handeth a kindly fortune down from sire to son, bringeth at another time some sad reverse, together with the heaven-sent bliss…” (In Sir John Sandys translation.) It’s the reversibility of fortune Meyer appears to be addressing in these lines, undoing his own folly in thinking of metaphor as colors.

The force that keeps these lines in motion is as volatile as it is sudden. How? How does he move so gracefully between lugubrious thoughts and fleeting perceptions? In 1915, Freud wrote a short essay, “On Transience,” published the next year while Europe was sundered by war. In it, Freud describes walking in 1913 through the Dolomites with a poet who lamented all he was seeing, “disturbed by the thought that all this beauty was fated to extinction.” Freud, phlegmatically, couldn’t muster the desire to contradict the poet with the insistence that all this beauty was eternal, even as he somehow sensed that “this loveliness must be able to persist and to escape the powers of destruction.” The beauty of the Dolomites wasn’t in its transience; rather, “[t]ransience value is scarcity value in time.” That things don’t last makes them better. And more mysterious. Freud admits that while mourning for something lost is one of the most natural things we do, it remains a riddle at the core of our capacity to love. Why doesn’t love withdraw when the object of our love ceases to be present? Instead, it remains attached, winding and rewinding around the transience of the lost love.

Freud’s conversation with the poet was a premonition of the Great War that would destroy the beauty of nearly everything he knew. We can discuss these things, we can try to solve the riddle of them, but beyond them, in time, prodigious and harrowing forces loom, gathering power. Our feeling for transience, its movement and heaviness, is a thing we are at times permitted to explore. Not because it helps us cope or survive but because the sequence of things that do not follow in our mind are what constitute us. “The logical conclusion then,” writes Meyer,

***

Postscript

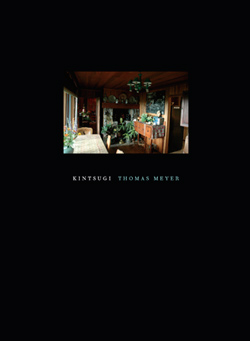

Kintsugi is the third book of Meyer’s poetry to be designed by Jeff Clark; it’s as luminous and subtle as the other two, At Dusk Iridescent (one of the most beautiful books of poetry, in terms of its design, in my library), published by the Jargon Society in 1999, and daode jing, published, like Kintsugi, by Flood Editions in 2005. All three are splendid. Kintsugi has an impressively subtle design, clothed in mourning but with a dusk-like lighting (signaled by the cool blue color of the inside covers) shining through. It’s a handsome little book, small enough to be carried in a pocket, short enough to be read in one (intense) sitting. (As I first did, reading it on the CTA from downtown to my neighborhood. I almost missed my stop, so absorbed did I become in the book.) The front cover features a glossy color photograph by Reuben Cox framed in matte black. The photo shows a dining table with a tablecloth by a window, light flooding toward lots of plants crowding the floor and table. If you squint, you’ll notice through a doorframe the tiny figure of Jonathan Williams sitting in a chair, legs crossed, the same light washing over him. He’s reading. The image, and more largely and subtly the book, have a telescoping quality, or a tromboning one. You can feel the image receding from view even as you are staring intently into it.

I can’t help but read Kintsugi personally; it’s part of a system and lineage to which I feel bound and devoted. Jonathan Williams was Ronald Johnson’s companion for over a decade through the end of the 1960s. As Williams’ relationship with Johnson concluded, when Johnson left Aspen, Colorado on the back of a motorcycle headed to San Francisco, his relationship with Meyer shortly after began. (The experience and effects of this break-up are recorded in A Garden Carried in a Pocket, a collection of Williams’ correspondence with Guy Davenport, edited by Meyer and published by Green Shade in 2004.) I never met Williams but his work has always been important to me, not only because of Black Mountain and his connection to Johnson, but certainly significantly because of those. After Johnson died, we exchanged telephone calls and a few notes; Williams would send me Jargon publications from time to time (including At Dusk Iridescent). Though I have followed Meyer’s work for years, beginning to collect his books when I was back in college, we became friends only recently. After Kintsugi was published and I had read it, I wrote to him to tell him how extraordinary I found the book. In reply, he wrote me:

Freud could have put it no better.

***

Peter O'Leary's most recent book is Luminous Epinoia. He lives outside Chicago.