Reviewed October 5, 2012 by Daniel DeKerlegand.

In order to examine the contemporary mind by way of traditional Buddhist meditation, Dhompa resists the “narrative self” in free associative leaps that patiently explore the links between words that commonly pass by unnoticed. For example, in the titular poem, she begins the book by writing:

It is not everyone’s desire to swim like a fish.

I have a little dog that behaves like a cat,

it is not his fault he cannot pass the discipline test.

A fault line runs through the city center

sullen as a stretch mark under a dress;

we believe our undoing comes from one source.

The first sentence establishes the undoing of the narrative self by establishing that “desire” determines the identity of the being itself, and so therefore the dog that “behaves like a cat” is not at “fault” for a lack of dog-ness. In this way, it is the being’s sense of play that determines its self, as much as its biological determination. The “discipline test” is thus man’s feeble attempt at revising the being in order to sufficiently understand or use it. Similarly, the “fault line” results from a natural process revealing itself beneath a man-made, “disciplined” structure, i.e. the “city center.”

The word “fault” is here understood to exist in a different semiotic sphere than “at fault,” or a possessed fault such as “his fault” or “her fault,” as the subject of blame. Still, the one signifier carries two signifieds, and thus our “undoing comes from one source.” This undoing could be the shattering of the illusion of determinacy in both language structures themselves and the hierarchies they create, such as the inherited “great chain of being” that is most immediately present in the technological manipulation of nature. Through this meditation on the illusory, Dhompa is able to use post-modern aesthetic techniques in a distinctly Buddhist manner.

Dhompa’s most apparent American predecessor seems to be Lyn Hejinian— particularly in her 1984 book, Redo— as both are poets primarily of thoughts; like Hejinian, Dhompa makes an effort to think though or around her own thinking, in order to remain aware of the present while at the same time experiencing it. In the relatively vertical experience of reading, this is achieved through a succession of lines that appear deflective but in fact reflect underlying readings of their preceding lines. In the poem “Selvage: for country,” Dhompa writes:

Thoughts do not form words to frame the world

as I do. Perhaps desire should be the measure

for action. How will I maintain flowers or decency

in this downpour? He loves me. Such an ordinary

arrangement alters circumstance and favors,

a narrative henceforth to be held as example

of authenticity.

Immediately, Dhompa devises a negative logical statement within the first line, that “thoughts do not form words to frame the world.” As the sentence follows through the line break, the agent of action is revealed to be the “I” of the poem; thus, the paradox here is that, though the poetic line reflects the “thought” of the poet, the words themselves that compose the line are, in fact, mere frames created by the conscious self and are illusions of the original thought.

The poem continues by stating that “perhaps desire should be the measure/for action,” with the word measure taken to mean both a means of assessing an “action” and poetic measure’s inherent function in lineation. Dhompa’s maxim could mean that the only method to understand “action” would be a measuring of “desire,” since words are inept frames, though desire itself is as illusory as a thought. However, as Williams had it in his 1948 essay, “The Poem as a Field of Action,” “The only reality that we can know is MEASURE”; in this context, through the ambiguity of the signifier “measure,” the maxim could mean simultaneously that desire should become or embody the poetic measure, and thus reveal a more “authentic” reflection of action or thought. Dhompa enacts such measure when she continues “How will I maintain flowers or decency/in this downpour? He loves me,” reflecting a conscious digression from “flowers” to “decency” in order to make apparent the “frames” of language that itemize a spectrum of desire and thought. Even this “ordinary/arrangement,” however, alters the “circumstance” of the poem and reader, creating a “narrative” despite its authenticity to the original thought. In My rice tastes like the lake, Dhompa’s poetry has similarities to that of some contemporaries, in the sense that she explores a post-Ashbery poetic consciousness by way of the transformative power of the line. The distinction of the book, however, lies in the fact that for many post-Ashbery poets, the semiotic subject is the tonal register— reflecting socio-political signifiers in the cosmopolis— whereas Dhompa’s semiotic subject is the illusory nature of the signifier itself.

Works Cited

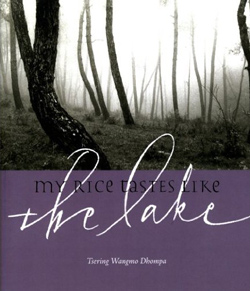

Dhompa, Tsering Wangmo. My rice tastes like the lake. Apogee Press: Berkeley, 2011.

Williams, William Carlos. Selected Essays. New Directions: New York, 1969.