Reviewed August 24, 2012 by Johanna Skibsrud.

“Or is speech a subject’s very constitution and assembly, which then makes experience possible?” asks Erín Moure in her latest collection The Unmemntioable, published this past spring by House of Anansi Press. Readers of Moure will be accustomed to the way loosely translated or re-interpreted texts—with a heavy preference for the work of 20th century Continental philosophers—serve as touchstones within her own work. Because these outside sources are seldom accompanied by the usual signposts it is sometimes difficult to tell where the line between Moure’s own text (read: subjectivity) and another’s is drawn. The reply that follows directly after the question posed by Moure above, for example, is set apart from the rest of the text with quotation marks but not attributed to its source, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, until a few lines later—and then only indirectly. “Subjectivity is nothing more than the aptitude of the speaker to posit its self as ego,” Moure quotes Agamben as saying: “it is in no way definable by a feeling an individual might hold in their ‘inner forum’ or ‘sanctum.’”

In a classical context, as Simon Critchley explains in his Ethics,

the subject is the subject of predication; […] that which persists through change, the substratum, and which has a function analogous to matter (hule). It is matter that persists through the changes that form (morphe) imposes upon it.

Exposed in Moure’s collection are the various substrata of “subject” matter, a record of the shifts and changes, and most palpably the traces, of that which remains unchanged even by and through the imposition of its own form. In The Unmemntioable, language and subjectivity become material. Text (Moure’s and others’, and in a variety of languages: English, French, Romanian, Ukrainian…) and meanings collide and compress—sometimes sitting so closely alongside one another that it is their differences and disjunctures, rather than their similarities, that are emphasized. At times, they would seem not to touch at all.

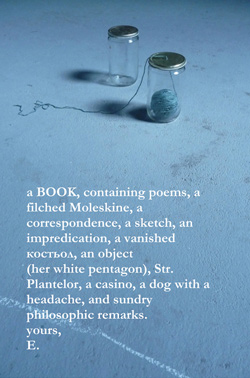

But this seeming failure is integral to the structure of the whole for Moure. Language is matter, but it is not only that, and the ways in which the materiality of language in Moure’s poetry is brought to the fore conversely calls attention to this. Following Emmanuel Levinas, another philosophical voice echoed within the collection, Moure strives to delineate a space of contact between disparate subjectivities and possible meanings precisely by delineating their ultimate and unbridgeable difference. The Unmemntioable personifies and charts this difference by illustrating the relationship between Moure and her heteronym Elisa Sampedrin, with whom readers of Moure’s previous collections O Resplandor and Little Theatres will already be acquainted. Sampedrin is so literal an embodiment of the “difference” at the root of language—and thus the processes of translation that are necessary to reading, writing, and indeed of perception itself—that she acquires actual physical traits, an address (if shifting), and the authority to influence the author’s own literary, as well as (ostensibly) physical presence and direction.

The success of Sampedrin’s role—which also exposes the relationship between her and the author—rests on her satisfying concreteness both as a character and plot-device and as an intriguing abstraction of the act of translation itself. She is not simply a medium—just “E.S. and her prosthetic gesture: language,” a space of the between—but rather simultaneously that which is measured, immediate, and familiar, and that which will always remain strange, just out of reach—“unmemntioable.” “[T]hought,” writes Moure, “cannot be constrained in “je” or “I” alone.” Elisa Sampedrin (E.S) is the “ex-plosivity across membranes”—experience and desire which cannot be “constrained” within even the most deeply entrenched notions of singular subjectivity. She is the material signifier of that which the sign can neither embody nor express and, indeed, her very presence within the text points to and defines her absence; in this sense, she can be understood as being “written under erasure.” She acts as a physical expression, in other words, of the dualities and paradoxes at the heart of language and experience, serving to underscore the parallel dualities and paradoxes at the heart of every consideration of subjectivity.

However, issues of language and subjectivity are not conflated for Moure. Contrary to the presumption of a surprising portion of contemporary criticism of Moure’s work, hers is not an interest in language as a fact in itself, with an emphasis on its materialism only as obstacle and its ephemerality only as refusal to be fixed. Equally, her intention is not to arrive at a sense of greater senselessness; nor to assemble only for the sake of exemplifying the impossibility of assemblage. Moure’s poetry is instead interested precisely in the “explosivity across membranes” that “E.S” represents in The Unmemntioable—of finding ways to render sensible the complex sensory experience that exceeds and therefore shapes language. “The brain doesn’t care what body or prosthesis act as conduit for sight,” she writes. What interests Moure in this collection is not the prosthesis (language) itself, but the sensory range of motion within which “touch and sight merge.” That is, the continuous generative energy and impulse of thought and experience that invents and instructs the prosthesis. “Turns out,” remarks “E.S.” in a section from O Resplandor, “the tongue can be activated to see.” She then continues on to relate the following—apparently gleaned from an (un-cited) magazine article:

Given a camera port linked up to microelectrodes on its wet surface, the tongue carries a charge easily, receives visual information through a strip of red plastic from the camera-machine, and transmits this info through nerve fibres to the brain. The part of the brain that processes visual information is activated by this transmission: the brain doesn’t care if its visual impressions don’t come from the eye. So the tongue can see. Speak too. But, also, see.

The literal contiguities explored here between the “nerve fibres” of the brain and the sensory information it receives point to the contiguities between languages, histories, ideas and subjectivities explored throughout O Resplandor, and the rest of Moure’s work. The Unmemntioable follows in this tradition, and in many ways can be read as the next installment in a project that Moure began at least as far back as Little Theatres. As in the earlier collections, the unsettling of the subject in this latest work through the dialogue between the external construct—the author, “E.M.”—with the imaginative (internal) construct—“E.S.”—works not toward the disestablishment of the singular “I” and the meaning it produces, but instead toward its performance and investigation.

Accordingly, it may be useful to think of The Unmemntioable not as a collection of discrete poems but instead as a mode of prayer. As Michal Govrin writes, both prophecy and prayer “project a future, and bring it by through the power of language, the power of performance.” Moure’s poetry enacts rather than describes, and like prayer, its “most intense expectation […] is for the listener.” Like prayer, it reveals “an expectation and an outrageous confidence — of being listened to.” The prayer itself, explains Govrin, establishes the grounds of its own address. It creates it, opens it, and in this way, “it does not only create an ‘I’ who has the power to address, but also the addressee.” Moure’s latest collection similarly works to establish this convergence between addresser and addressee—in order to open up a space of listening. The gaps and fissures inherent to language and subjectivity are revealed, through the resulting discordance, not in order to disrupt or distract from meaning, but in order to promote this attentive, sensual space. Moure maintains, however, a reflexive skepticism as to the ultimate veracity and reach of her investigations. “The human eye is more acute than the camera lens,” she writes in Chronica Seven of O Resplandor. “For one thing, it chooses what to ignore in a scene, without our even knowing it.”

The Unmemntioable is conscious of the way that it also, necessarily (even when it would seek not to), delimits for itself a provisional framework. “Unfortunately, censure has cut history up,” she writes—emphasizing the “cut up” quality of the history recorded within her own book. It is the cuts—the signs and “censures”—by which we organize history and experience that are at stake in The Unmemntioable and poignantly confronted through the layering of various narratives within the collection. One of the most compelling of these narrative “substrata” is “E.M.’s” journey to bury her mother’s ashes in the Ukraine, a country which had at one time sought to finally “censure” the family’s presence there through the violences of war and time. But again it is not history as such, or what is lost, that is the ultimate “subject” of this remarkable book—nor is there any effort to find some cumulative or transcendent explanation or closure to the account. When it comes to Moure’s approach to history, “E.S.’s” remark in O Resplandor: “If anything, it’s the fault of reading,” is apt. Moure’s larger project—worthily continued by The Unmemntioable—is to ask us to develop the territory of reading where “touch and sight merge,” where the deep structure of subjectivity can be read against the gaps and fissures of language that her poetry describes.

Works Cited

Critchley, Simon. Ethics—Politics—Subjectivity: Essays on Derrida, Levinas, and Contemporary French Thought. London and New York: Verso, 1999, pp. 51.

Govrin, Michal, Jacques Derrida, David Shapiro et al. Body of Prayer: Written Words, Voices. New York: The Irwin S. Chanin School Architecture, 2001, pp. 35.

Moure, Erín. O Resplandor. Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 2010, pp. 19, 95, 108.

---. The Unmemntioable. Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 2012.