Etel Adnan. To look at the sea is to become what one is. Thom Donovan and Brandon Shimoda, eds. Nightboat Books.

I had read and admired several of Adnan’s books but hadn’t known the extent of her accomplishment, which is tremendous, until now. In fact, I may not have been so impressed by the power of a poet’s work since I first encountered César Vallejo’s poems as a teenager. If any of her small, early poem sequences were reprinted this year, “A Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut” or “Five Senses for One Death”, for instance, they would appear on my list of bests. Like Vallejo, Adnan has written through several linguistic modes, sometimes at the edge of comprehension, sometimes with prosaic plainness, but always with remarkable acuity and conviction. The two volumes here are strangely identical in size, giving the project an air of inevitability, which troubles me somewhat, as one of the strengths of this work is that it seems to battle, in real time, against inordinate power and bad odds, but otherwise, it’s marvelous.

Aimé Césaire. Return to My Native Land. Archipelago.

An actual instance in which the ground-breaking and genre-expanding aspects of a work inspire a libratory new thinking. A rarity for many reasons. And even now, eighty years after its first publication, the text remains a reminder of what poems, and writing more generally, can signify or include. The book concerns itself with issues that, while already very old at the time of the book’s publication, are still current, which is news to FOX, if nobody else: the agency of the legacies of colonialism and slavery within the context of public and private identities, as well as the consequences of exclusivity and restricted access in literary canonicity. The text is most famously connected with Negritude, and explores ways in which influences both endogenous and exogenous collide in that concept, and provides a particularly exacting and fierce accounting of some of the most terrifying ramifications of the latter. The book is, in fact, concerned with many forms of inheritance, and while novel in its construction, openly converses with many different cultural forebears. When asked what separates this work from the works of two famous Frenchmen (Lautreaumont and Mallarmé) with whom certain aspects of this work can seem both contest and homage, John Berger, one of this edition’s translators recently replied, “the particular character of his rage.” That’s only one of the emotions present in the book, but it’s a remarkably powerful and also very useful one.

Claudia Rankine. Citizen: An American Lyric. Graywolf Press.

Claudia Rankine is one of those artists whose every effort interests me. Her video poems, transcripts of whose texts appear in this volume, are some of my favorite poems of the past decade. And her prose works, which are nonetheless lyrics as the subtitle of this collections alerts us, are some of the clearest, most thought-provoking you’re likely to find about illness, anger, race, sport, agency in art making, and basically, American life at this time. I only wish there were more and that they appeared more frequently. A curious question posed here is one concerning style. Rankine has recently stated that she wants the text to “disappear” so that no one need ask what she means. That’s a deeply surprising statement from the author of “Plot” and “The End of the Alphabet”. That’s another reason why this book is so extraordinary: it’s another instance of Rankine challenging the limits of what poetics includes, where it appears and to whom it belongs. To me, this book makes smoke of award shows and the interest of whether or not it win the National Book Award is obviated. I’m not sure that a book is necessarily the best way to document her work anymore, but it’s still a very good way, and I’m glad to have it.

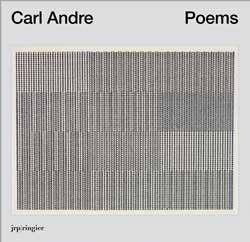

Carl Andre. Poems. JRP Ringier.

From about 1958 to 1970, Carl Andre made a body of poetic texts (“pages”, as he sometimes called them), as compelling as anything published during that exceptionally fecund era. The only problem was: few people saw them. One exception was Susan Howe, with whom Andre shares an interest in New England’s historical record. My wife, Caitlin Murray, and I have had the opportunity to live near a large body of Andre’s poem works for many years, as they are permanently installed at a museum that’s located in our town. In fact, Caitlin gave a nice talk about these works last year that I recommend, in which she describes their constructivist orientation (a nonce form of constructivism, which isn’t related to the Russian visual art movement) and their indebtedness to Ezra Pound’s paratactic strategies. Ringier’s is the only affordable publication of any of Andre’s poems in many years and very nearly the first widely available publication. These works are so good, and so integral to 20th Century poetics, that I would recommend buying the Catalog Raisonné when it appears next year, although like the Complete Works of Larry Eigner, which is equally integral, the price tag will be big.

Caroline Bergvall. Drift. Nightboat Books.

There seems to be some dispute about the lyrical / conceptual divide in our discourse, which speaks to whether one or the other has some inherent improved capacity to relay some quality or other. Maybe one provides a more precious access to politics or grief, for instance. I basically have no use for this mess and will simple quote from a conversation between Gregg Bordowitz and Amy Silliman which Alejandro Cesarco published ten years ago: “BORDOWITZ: Does a model of conceptual painting dominate now? SILLMAN: I don’t even think conceptual painting exists... It’s a ridiculous non-category. All painting is conceptual and is also partly driven by desire.” But, let me backtrack from my disdain, to address the subject at hand, Bergvall’s excellent book, which happens to demolish this false and pernicious dichotomy, among other things.

Bergvall’s “Drift” is in some ways a wildly expansive translation of the 10th Century, anonymous poem, “The Seafarer”, except some of the poem will seem to have been left untranslated in some passages, or accidentally translated into languages other than English in others. It also includes a series of drawings pertaining to the letter þ (“thorn,” as we say it), present in the original poem, but which disappeared from English orthography in the age of printing although it has persisted in Icelandic. And, there is the saga, retold in a combination of newswire and forensic fashion of a group of refugees whose overcrowded and ill-equipped raft was adrift for several days in the Mediterranean, despite the proximity of many civilian and military crafts from various nations who knew of their presence. The book also features a long prose text in which the author / translator steps from behind the curtain of the book, and makes an appearance, in order to pose a series of questions about performance, translation, gender, kinship and the trace, each of which carries us distantly beyond the conventional realm of contemporary poetry and books in translation, and helps us to rethink our roles in all of this.

Moyra Davey. Burn the Diaries. Dancing Foxes Press.

This one might not be poetry for everyone, but I’d say it’s at least poetry-adjacent, and helpfully so. There’s a lyrical kernel to the writing here, a concern with the construction of the performing self, and a concomitant consideration for the structure of the book in which such a performance takes place. There’s a number of queries (concerning the document, the survey, abjection, and performances of the self) throughout and they’re, frankly, more nuanced than what I usually find in books of poems. The book consists of a sequence of titled diary entries, (“Money”, “Discipline” and “Albums” are all included) mostly concerning the work of Jean Genet, but also concerning the work of Hervé Guibert, and a few others; questions pertaining to the nature of artistic self-presentation; and images of Davey’s own photographic work, which appear throughout. The book concludes with the diary of a friend, Alison Strayer, consisting of responses to Davey’s diary, which she presumably shared during its composition. There’s an uneasy question posed by both authors and the book itself about the viability of Genet as subject for this work, which is significant. What subjects do we have the right to make into subject-matter? Even the mere typing of the phrase bodes evil. “The words of the dead are modified in the guts of the living,” yes. But is that knowledge enough? I don’t know. Another important point to make about this one is that rarely do I find books in which images, the production of images, writing and reading oneself, looking at and reading others, all come together so thoughtfully and poignantly.

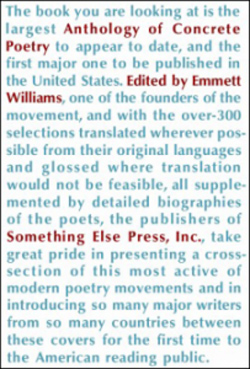

Emmett Williams, ed. Anthology of Concrete Poetry. Primary Information (Reprint, originally published by Something Else Press, Inc., 1967).

Rightly or wrongly, I have always associated the end of Concrete Poetry with the publication of this anthology. Despite this, there’s a curious, and even hopeful poem in the book that doesn’t receive attribution. It’s the words “To Be Continued” printed on the final page, after the biographies. It remains true, even though the future may not have been what some of the participants expected. Here’s another poem they might have included:

.03896103896104

That’s the percentage of women who appear in the book, rounded to the nearest one hundred trillionth.

I’d like to add that the book includes Ronald Johnson’s “Io and the Ox-Eye Daisy” in its entirety, which is great, not least because Johnson provides a commentary that includes the lines, “Io is a poem meant to be read by moonlight” and “The first word is a phosphorescent moo into the darkness”. A phosphorescent moo into the darkness!

Jimmie Durham. Poems That Do Not Go Together. Wiens Verlag and Edition Hansjörg Mayer.

This book, consisting of poems written between 1966 and 2014, is a wonder. Durham, who is best known as a visual artist, has been making poems for a long time, though his last volume to appear in the States , “Columbus Day,” did so more than twenty years ago. The poems here are often politically charged, humorous, heartening and disheartening at the same time. They sometimes remind me of Gilbert Sorrentino’s poems, which I also love, though an altogether different kind of Sorrentino. Durham is marvelously disdainful about the fact that his works, which frequently bear the mark of his involvement in the American Indian Movement, might be treated like those of a political pamphleteer. To address this fact, the register and mode of address changes, sometimes several times within the same poem, but it does so without losing the plot. The work hits hard and foregrounds a world of loss, of exploitation and suffering, but it can still manage moments of tenderness and humor.