Reviewed March 1, 2019 by Daniel Moysaenko.

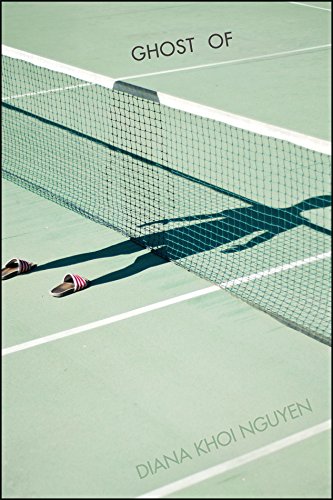

The elegy, as students of Western Anglophone poetry know it, stems from the Greek elegiac distich initially employed for erotic love songs and political satires. And pastoral laments or idylls by Theocritus in the 3rd century BCE are often considered the originator of the genre, their subject matter being a prototype of modern elegies. Topics of loss, sorrow, shock, anger, longing, and resolution became common, and the classic tripartite function of the elegy was cemented: to lament, praise, and console. These lyrics also typically made use of apostrophe, allusion, incantatory refrains, idealization of the rural, nonhuman elements enlisted in mourning, and apotheosis (a divine ascension or transmutation). But—as with any genre—cultural, political, and literary shifts over time altered the texts, from anti-heroic to self-elegiac and on. Nguyen’s debut full-length, a finalist for the 2018 National Book Award, Ghost Of, revolves around the death of the speaker’s brother. It necessarily participates in this lineage but looks to postmodernist techniques and 21st-century sentiments to adjust and climb out from under it into a more complicated space.

A noticeable feature of the collection is a series of family photographs that the deceased cut himself out of. In addition, adjacent or overlaid poems are composed in the shape of the missing brother’s figure. And white space matching that figure punches through prose poems’ blocks.

The prose poems’ language is not excised by the gap or ghost, however. Instead, one might say the text is interrupted and, in being forced to work around an absence, innovate. Phrases or words skip over the white space and are split into stuttering new morphemes or phonemes: “not eve ry one has a sound,” Nguyen writes, and “I stretch the replay across the y ear, and longer.” For the unsuspecting reader, this may take adjustment but the adjustment is quick. And the reward is a highly musical, often wrenching experience. For a reader of avant-garde poetry, this manipulation of text might recall Susan Howe’s interest in linguistic roots and her cut-up, Xeroxed lyrics. Sense remains symbiotic with sound here, and Nguyen’s poems become uniquely accessible and emotive in their materiality. The brother’s name, Oliver, for example, becomes “elver”—a young, migrating eel—and the speaker repeatedly compares him to the “e / ely eellike” and compares his life to a return upriver. Repetition, syntax, and limited punctuation allow the prose poems to harness two of the genre’s competing possibilities: grammatical extension and claustrophobia. Elegiac chant contributes to this, as Nguyen writes, “I am glad that you are glad that you are I am glad that you are I am glad that you are I am glad that dead I am dead I am dead glad that you are glad dead glad that you are dead are you dead.” The complication of combining clauses and idioms like “dead glad” intensifies then relaxes as the poem moves on, though the melancholic echo chamber is not isolated. The obsessive nature of mourning (however brief or prolonged) ensures such linguistic, sonic, visual, conceptual, and emotional reworking.

The book’s small, shaped poems are similarly beholden to form. A photograph’s cut-out becomes a container or void to be filled by language. Nguyen questions and answers this impulse: “we bewilder what we fill in what bewilders us to fill in what.” At the same time, she often titles these filled-in spaces “Gyotaku,” after the Japanese printmaking method of rubbing or pressing ink and paper against a freshly caught fish. With this in mind, the poems depart from cut-outs and the words are cast as inherent features of a body, now made visible. Here, the body’s edges mean that line breaks unsettle words’ wholeness and sentences’ prosody. Yet, often, syllabic and syncopated rhythms guide the reader through the splintered texts. For example, “mind / ful of / the sett / ing he co / unted off / the seconds,” one part of “Triptych” reads. So while the formal aspect reflects elegiac topoi—the dead’s presence in absence, or loss as disruption and all-consuming lens—it also generates a singular music, insistent yet fresh.

In the midst of these new forms and some serial poems, Nguyen strikes upon moments of clarity, like insights or disclosures, with such ease that it seems as if she merely stumbled upon them. At the same time, the poems display a speaker searching:

Is it not useless to pursue, for its own sake, the urgency of a previous day?

I loathe it—the likeness of a brother living in the likeness of a body, with lips and

hands and eyes that keep nothing in, nothing out

I would give you my other face to touch

I love them—the likeness of a woman, in her arms the likeness of a child

Once more I begin to move in the direction of animals

The difficulty of the body and of proper mourning (what to praise or remember, how to behave) grow increasingly complicated in the collection. And the difficulty of addressing a life, death, and grief grows sharper, more unlikely to be resolved. The speaker imagines the brother’s mindset, hoping to forget “that just because it was like life, / didn’t mean it could be life.” Amidst the possibility of forgetting experience or knowledge, a crushing examination of escape and death emerges: “that you could come back to life / but not return to living. / And if you bypassed a war, a war / wouldn’t bypass you.” This finality seems matched by the last poem’s reverential, Sisyphean sentiment, “sma / ll, I am growing still and wi ll fill in for you, fill you in u / ntil the end; I will nev er give you up I will ne / ver give up I will never.” Where “the end” and the filling-in become complete—that is, consolation after lament—is uncertain and indefinitely postponed.

But elsewhere, the speaker circles this postmodern indeterminacy and suspension of resolution. Particular realities inform and multiply the poems’ handling of death. Issues of mental health, suicide, immigrant experience, and cultural norms intersect, illuminating the variances and familiarity of processing loss. “The future holds good weather,” the speaker begins, “War gets everything it comes for.” This forestalling of the future, with hope after hardship, painfully reframes the brother’s suicide as well as the story of a young man emigrating from Vietnam who died once he reached land: “the journey’s end too much to bear.” For some readers, Ghost Of will be a poignant, demanding book, severe and dark, though it is finely calibrated with moments of airy light and beauty, detailed like a talisman. Moreover, some readers may argue that the collection takes up the elegy’s mantle, minus consolation, with never-ending grief and remembrance, like a bird’s “lyric out of sync / with melody.” Scholars might point to famous elegies, by Jonson or Milton or Akhmatova or Hughes or Auden or Plath or Clifton, for solutions to the problem of evolving genre, spirituality, and customs. Ghost Of seems to ask the avant-garde to address questions that canon and intellect have been unable to satisfy. “Coda,” after quoting Bruce Lee, narrates a woman laying stones in her yard: “her mo / saicking is slo / w,” Nguyen writes, “her eyes s / earching for / the right sh / ape to fill t / he gap to b / ridge from / here to t / here.” As a kind of ars poetica, the poem intimates the formal process’s potential aid in openness, connection, understanding, or comfort. The final line break literally turns “there” into “here.” As water becomes its container, so too, it seems, language and the speaker and the deceased become wherever they are. Nguyen, here, inaugurates a theoretical apotheosis, one grounded in possibility. Rather than avoid answers or declarations, the book continues to push. The speaker even wonders about redefining loss and asks to be told “that what we lost as collateral is also a gift.”

A web of lineage and originality plus the grace and brutality with which Nguyen navigates the pain of writing inside/through/about a loved one’s death make the collection an admirable debut. To reconstitute elegiac tropes of water or thread or the pastoral, of obsession and sorrow and nostalgia, is tough enough. Ghost Of tackles it, re-seeing and –shaping material, absence, and time. In one of the collection’s last poems, “Reprise,” the speaker studies a dog’s movements, as if watching a ghost conduct the living: “A wild dog rose, unraveling the marvel of the field. / Most fragrant hum of all shed feathers. / Like some strange music: the world started up again around him.” Nguyen in radical, formal contortions of language and clear-eyed lyricism seeks to animate the elegized and—like the dead and the world—rise, unravel her marvel, and start up again. I’m eager to see where she goes next.