Reviewed February 1, 2015 by Bryanna Lee.

In If the Tabloids Are True What Are You, Harvey creates poems that thrill and interrogate “with the force of their dreaming.” This book combines the fantastic with the ordinary, grounding itself in both our world and others.

Like the tabloids, you might find yourself reading straight through or skipping to your favorite section as I did, eagerly anticipating the mermaid poems. You might also find yourself shaking your head at “Telettrofono” or searching for meaning in the ice-scenes of “Stay.” But whichever reader you are, you will most certainly find yourself “adoring” Matthea Harvey’s work in all of its sharp, innovative, stellar esteem.

Among the blurbs on the back cover, Craig Teicher describes Harvey’s work as “adorable.” But if we’re hunting for single-word descriptors, If the Tabloids Are True What Are You is above all sensational, firmly rooted in rich world-building, literal and figurative imagery, and ever-present dualities. Tradition and invention. Constellations and animals. Elvis and Shakespeare. Mermaids and Martians. And though several of her poems were commissioned, Harvey is such a deliberate, skillful writer and artist that this book is as carefully organized as each poem.

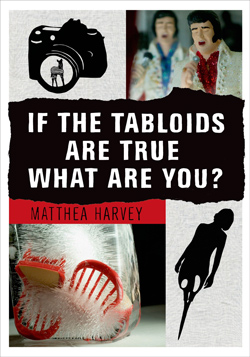

My first impression of the book was the Table of Contents, a spectacle itself. The layout, initially seeming more suited for photography than poetry, promises that this is no ordinary book. This is further evident in the fact that 17 poems have images for titles.

The shattering and inventive voices of this book are only enhanced by the images that accompany them. When initially opening If the Tabloids Are True What Are You, I was concerned that juxtaposing poetry with images would unnecessarily illustrate the subject, limiting the reader’s imagination. However, Harvey’s images skillfully avoid this pitfall, serving as poems in their own right. This is most clear in “Stay,” a poem (and even a title) composed entirely of ice cube artwork. A male doll is trapped upside down in one ice cube as if frozen in a moment of anxiety on his way to an important meeting. Chairs are trapped in—or splintering out of—others. The series ends with my two favorites: the doll of a young woman only half frozen in ice, seeming to be deliberately walking into it, and finally a child in a melting ice cube, which together make me feel like the story told through these images ends on a note of optimism.

Perhaps most memorable of all, though, are Harvey’s mermaid poems, which read like stories of self-actualization. These are juxtaposed with silhouettes of mermaids who are fusions of both woman and object—half human, half tool. “The Objectified Mermaid” begins with a photographer shouting “Wistful mouth, excited tail! Work it, work it!” Despite familiar themes of objectification, readers can’t help but smile at the playfulness of this scene. Harvey often uses these moments of humor and brevity early in her poems to make the end all the more disturbing: “When asked if she’s tired, she lies. A downward spiral means the opposite up here.” Ultimately, Harvey’s mermaids are not romantic or merely whimsical; they are unsettling stories of women looking for names, place, purpose, and control over their own bodies.

What follows is a sharp departure from both stanzas and the sea: “M is for Martian,” an erasure of Ray Bradbury’s story “R is for Robot,” propels us further into themes of intimacy and loneliness even as it takes us light years from Earth. Harvey grounds us with her characteristic language with lines such as “Dirty flub funny lump.” While Martians and much of the hula-hoop section that follows seem like science fiction, the animal poems—still magical in their own right—focus more on real-world intimacy and the human need for connection. The speaker of “My Octopus Orphan” writes, “Though I hold it in the water long / enough, he never takes my hand. / He understands: there was the sea, then me.” This is a flip on the mermaid tales of ownership and objectification with the speaker seeking to establish intimacy through containment.

Similarly, the fifth section ties back to the ideas of agency mermaid poems; “The Glass Factory”—a poem in parts—tells the story of women workers trapped in a factory made of glass. “They used to / run their fingers along the walls, / searching for a way out, but that only / smeared the sky.” It is only by building a muse-like girl made of glass that they are able break free. When the description of the workers’ share the same spark of an idea, we feel it too: “Now as if their skull walls had / windows and each brain were / a clear, crystalline thing, the synapses / making temporary chandeliers / of thought-sparks in the brain’s / blank sky.” This tangible release of creative energy in both the workers and Harvey’s language is most evident in its last line: “Another holds a thermometer / horizontally, and uses its markings to measure / the height of the trees. The mercury inside / shivers in the newly imagined breeze.”

If you can’t tell already, this book reads like a mythology. Several poems seem to be building answers to silent, impossible questions, such as Why do we all feel so alone? and What does it mean to be part one thing, part Other? “Quick Make a Moat” begins, “Before the rain, only baseballs and baby birds fell from the sky,” as if the rain is to blame for all the difference in our world. Later, the speaker says: “Twos dwindled in every arena— / doubles tennis, duets, tangos. Why bother / to hold hands? We’d been singled out / by the rain for other things. The storm / clouds racing across the formerly blank sky / narrowed our options.” Like those in Harvey’s previous collection, Modern Life, these poems seem so connected to current events despite having been written years beforehand. While tabloids about who’s dating whom or which president should be impeached go out of fashion each week, Harvey’s work is timeless in subject matter. Could Harvey have known when asking “Why bother to hold hands?” that the summer of 2014 would be filled with Ferguson and Gaza?

With Robin Williams and an internet anti-suicide sensation? The image of the imagined No More Suicide Fox constellation serves as the title for one of Harvey’s most heart-wrenching poems. “We need a dog patrol that sniffs out / despair and a horde of someones who will ask every single person every single / day, ‘Are you okay?’ before another friend is found dead in the bathtub, on / the floor.” Subjects such as war and conflict and grief will of course resonate every season of every year. It is all too familiar, as so poignantly stated at the end of this poem: “I don’t want to talk about that fox. He’s pointing at people I know.”

In “One Way,” Harvey asserts that what creates conflict and tears people apart is the invention of the arrow: “once it landed, / it did what arrows do—it pointed.” Lines like this make us smile at the seeming simplicity, but there is a dark edge. The arrow leads to self-determination but also bullying. “The weatherman no longer / ambled aimlessly around our TV screen. / When he pointed at Chicago then Boston, / the people sitting on sofas in those cities / suddenly felt how very different from one another / they were.”

The book ends with “Telettrofono,” a piece originally commissioned as part of a sound walk. This marks the return to the beginning of the book, with Estelle Meucci reimagined as a mermaid. Appearing next to this longer work are stitched handkerchiefs, which Harvey crafted throughout the writing process.

These mermaids are fitting choices for opening and closing the book, with their hybrid selves and inherent dualities. Their presence is felt throughout the other sections, such as in the sonnet about William Shakespeare reincarnated into the body of the Michelin Man. Harvey’s poems fluidly balance between the human and the animal, beauty and objectification, self-control and possession. The handkerchiefs throughout “Telettrofono” so skillfully symbolize this balance between domesticity and the feminist woman (or mermaid) dreaming of another world.

I’ve seen If the Tabloids Are True What Are You shortened more often than I’ve seen it written out in all of its beauty, and have made a point of only writing it in its entirety. What is the top half of the mermaid without the fin? The title is a mouthful, but it’s worth spelling out in its whole richness. The book itself is worth it, too.