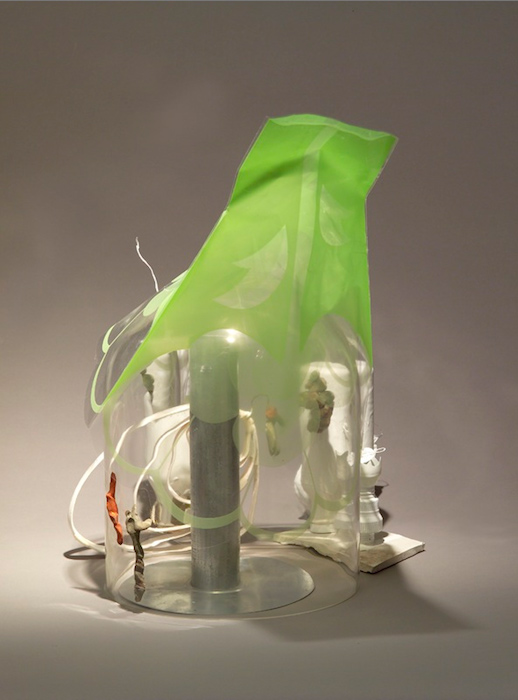

A cascade of light arises vertebra-like, shielding the filament, girding the pleats, enfolding the space within. Protected and ensconced within and outside, a stray gaze alights and flights of fancy clamber aboard. The vessel is almost transparent and could easily be mistaken for a momentary anomaly, unless you tarry. Then you know.

The panoply of things that fall between the cracks in the world and simply disappear is vast. Should we care why they leave, what becomes of them or where they end up? These disappearances are not typically studied for a sense of meaning, particular significance or any rationale. They just happen and, unless the missing item is an especially important personal possession or a radically rooted sentimental belonging; then mourning and conjecture are not in the order of things. Yet, if we step aside for a moment and observe the detritus that is such a large part of our world, we would notice that it is extraordinarily rich, assorted and multi-hued in forms, colors and textures. Were we to consider this junk as some thing, without preemptively dismissing it is mere debris, what would we imagine this thing doing or being or even having as a symbolic function?

Joan Tanner rescues all kinds of stuff from oblivion, salvages forms from nothingness, wrests sense away from unknowingness. She manages to conserve the state of limbo from which the stuff she employs in her art making derives, while simultaneously challenging a viewer to not ignore how these re-configured things surely add up to some other significant or, at least sensible and palpable, thing. In the realm of the sensory, where words and logic are not central to understanding, what these things could now mean is barely alluded to in the titles she offers. She draws allusions from the semantic halo or personal meaning surrounding her own perceptions of how these newly arranged works might be understood or acknowledged or appreciated. And she has a quite a knack for giving us the precise directions for turning our filtering minds off, as often our subsequent appraisals reveal.

I saw Michela in San Diego not long after she had returned from her trip abroad. It seemed like she had visited a lot of places and had made some rather important discoveries. She also told me this story.

After she arrived, she unpacked her bags and collected the few boxes she had mailed in from the different places she had been through in her travels. She was focusing on Western Europe primarily, and when the weight of what she was lugging around had gotten to be too much, she had put aside funds to mail things back to herself. So, besides the large mountain-climbing-style backpack she carried with her, 9 boxes in all had arrived back home, ranging in size from smaller to medium size, with postmarks from places such as Spain, France, Croatia and Slovenia. Cutting the boxes open and splaying the contents out on her apartment floor was a very satisfying start to the ordering and classification process of putting everything away, after suitable review. Clothes were easy to arrange in their customary drawers and closets. Some worn and dilapidated attire was disposed of immediately, and other tattered and torn clothing was put aside for future consideration, although it was more sentimental procrastinating than a serious desire to hold on to these things. The more interesting items were the odd bits and pieces of compacted memory she had decided to set aside as external proof of her transit through the various locales. There was a small black quasi-functional cup-like ceramic thing with an engraved surface (miraculously not broken in transit) from Gubbio, Italy, a thick, metal-studded and incredibly inexpensive leather shoulder bag from Budapest, Hungary, a small unusually shaped, brightly colored and meticulously crafted hand-woven swatch of fabric made of natural and synthetic fibers from Lugano, Switzerland, and a carefully sculpted miniature architectural frieze made of bronze or brass from Ljubljana, Slovenia.

About a week passed before Michela realized she couldn’t find her diary anywhere around the apartment: the one in which she’d recorded the details of her travels, and all the contact numbers and information about the people she had met along the way. The book itself wasn’t special or particularly well designed; she had picked out a rather bland looking journal without a leather binding or special color. She just wanted a tough, compact companion for her trip. Beside herself at the loss, she went through the garbage twice, uselessly (as by then since the trash from the week before had already been hauled away). She all but cut the backpack open along the seams and repeatedly unfolded and rifled through the clothes, books and printed material she had brought back. Still, she found nothing. All she could do was to wait and see if anyone out there that she had been in contact with got in touch with her.

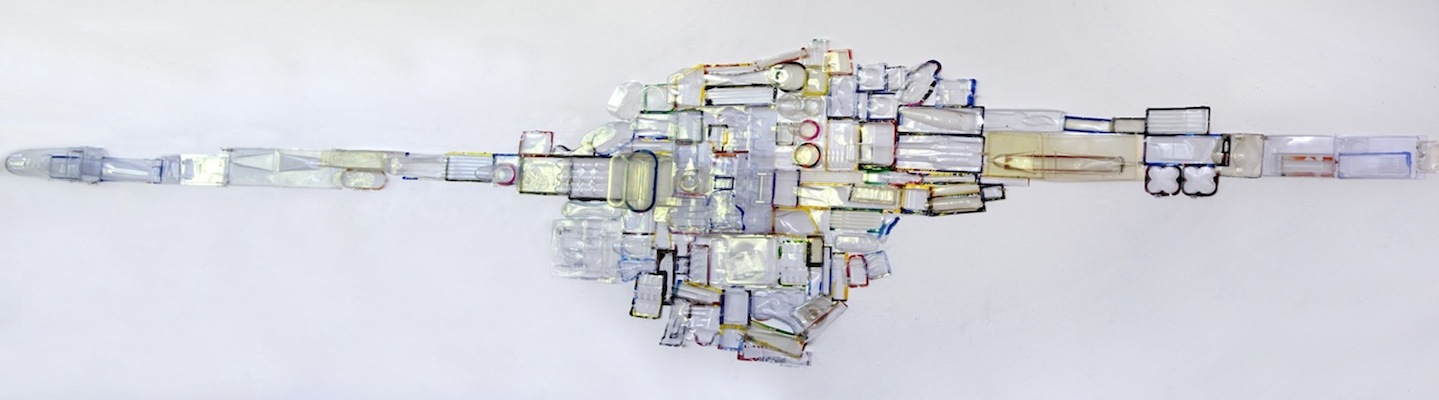

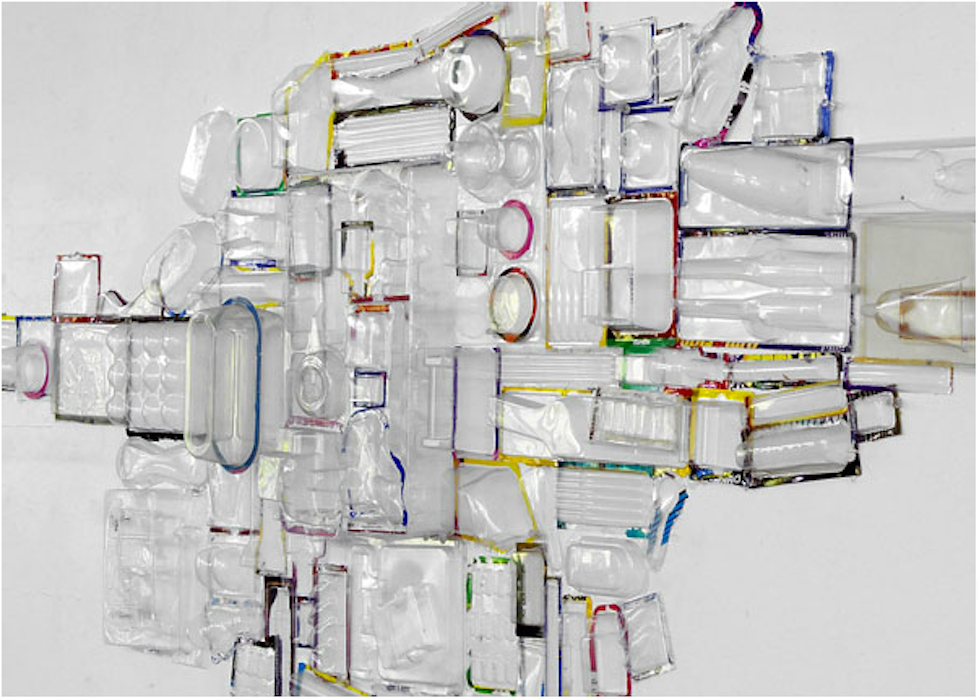

Click for larger image

Blisterpac, 2004

175 vacuum molded elements, wall mounted in a sequential format

228 × 54 × 11 inches

Click for larger image

Blisterpac (detail center)

Blisterpac? Trace Blips? Tribal Spec? Through a glistening, thick and spectral, the gaze searches for a stationary focus point that isn’t forthcoming. Now the mind seeks multiple focuses, even without the certainty that they are there and the gaze splits itself, looking for convergence. What about the boundaries, the distinctly colored borders, the passing delineations: corralling the senses overall into a momentary lull? Enough, more than enough, and yet always just a hint.

Something used to be seen through, to see something else: have you ever done that? Looked right past the direct source, the surface of what is there, already leaning into what is beyond that which is right there in front of you. Usually this is more of a metaphorical relationship than physical one, but not always. What is the over looked, the under noticed, the negligible and why is it so? Familiarity may breed some type of unconscious sorting process (categories of things not worth noticing) that in effect edits perceptual acuity; what we don’t notice. It may be that we are so busy weeding out information overloads that we scan and monitor the field for diverse kinds of litter and just step over it, without fully registering what just went by. Joan Tanner is drawn to the un looked at, the not noticed, the un important. She characteristically imbues it with a qualified dignity, not empowering it or nobilizing it but essentially removing it from the realm of the unseen. This makes it easier to see it all over again, notice it. She doesn’t really promote a teleology of the discarded but, much more interestingly, proposes a study of our own preconceptions and encourages our power to fantasticate. She traces out a set of possible connections and lets us go forth on our own. Or not. It is our decision, our option. She prefers to prompt, not to preach.

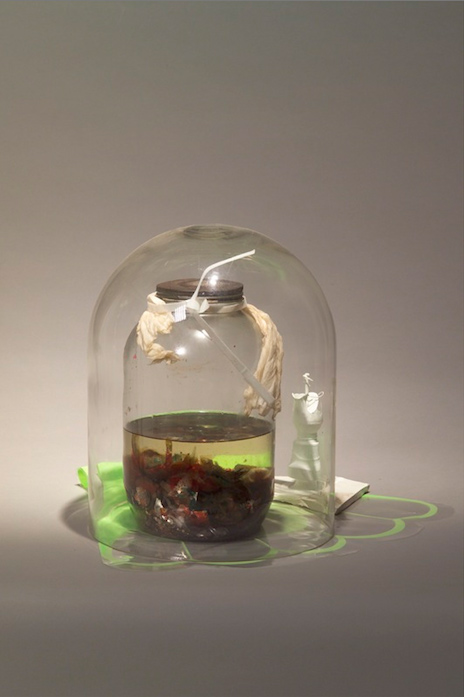

Click for larger image

Blanket & Lint, from the 1995 Close Scrutiny installation

blisterpac filled with lint, bulldog clips, wooden dowels

12 × 12 × 2 ½ inches

Click for larger image

Blanket & Lint (detail)

Gleaned from tatters that were inadvertently shredded and peeled away in an effort to bring everything back to an original state: without stain, without crease and without the accumulated burden of time and the earth. Not to purify: rather dosed displays, symbolic arrays, visible artifacts of penitence for having heedlessly emerged. Coming up from below, the residuals are preserved with an almost archeological scruple.

The scientific method sets out to observe some aspect of the world, create a hypothesis to describe those observations and then uses the hypothesis to make predictions and tests it through experiments and further observations. In appearance, Joan Tanner begins with a similar process. She observes and collects stuff she finds out in the world. She however conceals her working hypothesis from formula and language and, instead, places her experimental principle in the objects themselves. It is there where she also embeds her feelings regarding the hypothetical prediction she may have come upon. We are therefore left with the puzzling artifacts of this research and with the sense that we should be following her in her inquiry. Then we discover her explorations are not scientific at all. The noetic values she is working through are quite impossibly object-ive. They arc across a tangible intangible that we know and see and yet cannot put into reliable language patterns. Enough with language and predictions, she seems to say: how about trying waking dreams or whimsy?

Frayed, torn at the seams, worn thin, distressed, obsolete, out moded, out dated, unraveled, ragged, raggedy, tattered: all first-hand evidence of having been used by someone at some time for some reason.

In seventh grade my beige corduroy pants, tore straight through the left leg at the knee and my mother almost threw them away.

Sarah had a slightly lop-sided grin and an equally quirky sense of purpose. Maybe her one green and one yellow eye caused her to shift away from the standard attitudes of junior high school students in suburban Alexandria, Virginia. As part of her extra-curricular activities, she would invite classmates sitting behind her at her desk with a swivel seat to put their leg up next to her right hand and she would spend the entire algebra or Spanish class working a seam in the fabric of their pants back and forth into a even, methodical crease. She preferred working with jeans or, better yet, corduroy pants, especially the kind with a wider wale. Getting her fold to run perfectly perpendicular to the furrows of the fabric was one of her set goals. The other was to get the cloth to tear with usage and not by yanking on it or ripping it. In fact, if the fabric were torn before it was the right moment, she would move to another desk in the classroom and start on a new pants leg, snubbing the impatient classmate. When she was done with her work, the knee of the trouser would tear completely and flawlessly along her crease, usually from one side of the pant’s leg to the other. The pants were therefore essentially set to a zero degree of fashion: to be worn as a badge of distinction and as a banner of determinate design.)

Despite my protests, the beige corduroys were eventually and secretly discarded, along with a exceptionally thread bare tie dyed t-shirt.

Once honored and utilized, then spent, they are relegated to the pile of things forgotten. Were they to be resuscitated, what would they come back as: ghost, fantasm, shade? The collecting envelopes and vitrines enshrine and formalize the dignity of the loss and obduracy of things.

Here is a relatively common episode: when this thing was finally found, it had been lost, off somewhere else for a really long time. It no longer resembled what it once was. It now has an air of desiccation about it, like it was dried out in a kiln or furnace. The traces of what it once was as well as the obviousness of the location and the timing of its discovery make it apparent as to what it once had been. Thing is, it wasn’t that anymore, it was something else altogether before. Its oddness derives from it being familiar and unfamiliar at the same time, recognizable through crisscrossing circumstance and yet not quite right. It fascinates because it has come back from oblivion, been resuscitated in part (mostly in our memory). It was fatally half gone and heading out and away from us. How did it go? Why hadn’t we found it before? Are we saddened or predominantly mesmerized by its new half life, unable to let it go and powerless to bring it around again.

Can an object be pitied? Does it make us forlorn to come across a thing so consumed by time as to remind us of our own mortality? The dignity conferred on an object is probably only a projection of the person looking at it, but it does seem likely at one point or another that these phantom things push us to consider the sidereal effects of long periods of time on their material stratification and surface dissolution. They become husks and shells and, as such, we fill them with our inferences and our sentiments. We misapprehend them. When did you hold the last inanimate thing that you truly felt sorrow for it? Why did you feel that way and what did you do after feeling that way? Did a firm sense of embarrassment cause you to turn against the lowly cast-off and toss it quickly away again? Or did you furtively put it aside, not sure what to do next? Joan Tanner finds a way to induce in a viewer a sense of that state between feeling uncomfortable about the disarray we encounter and the longing to put everything in its rightful place. She places us at the center of the dilemma of recognizing that acting to save or discard something found in the world puts us in: how have we misconstrued them; heedlessly, subjectively and unmindful of their intrinsic value? Do we give in and put one more thing aside or do we give in and throw one more thing away? Give in? Give out?

Luisa and I were often invited to exhibitions before they were opened to the general public. We both wrote about art for local newspapers and the specialized press and were therefore given early access and a private viewing. The first time I saw her steal a part of the art work in an exhibition in Rome at the Quadriennale, I thought I might have been momentarily hallucinating. She glanced around quickly, opened her shoulder bag and bent down grabbing a figurine from the large quantity arranged in the installation on the floor. She then put it in her bag and snapping her bag shut, straightened up and continued walking along with the tour. It was all very fast.

We had been friends for quite a few years; she was a little older than me: a wonderfully curious and intense woman who loved to talk about art. Slight in build, with short blonde hair and penetrating blue eyes, she had a habit of tightly pursing her lips while she listened to anyone else talking. I thought it was kind of cute but a number of mutual friends found it irritating. Aside from the writing we both did about art, we shared an interest in Jungian psychology, though I was a self-taught dilettante and she taught this at the university along with art history, having obtained various certificates and completed a number of special studies.

Once I spent the night at her apartment after coming into Rome on my way through to Marseille: she had a small tidy apartment near the University, just off a main street. As a host, she was attentive, providing me with a little glass of grappa after dinner and making sure I was comfortable in her guest room. A one point during the late night or early morning, I got restless from the time change and decided to do some reading. So I got up and looked around for a table lamp or some reading light to put on next to the bed. I found one on a small side cabinet on the other side of the room, but I needed to move the cabinet over to the bedside for my plan to work. As I carefully moved the little piece of furniture over, I heard something fall over inside of it, so I turned the key in the lock and opened the door. Inside it there was an array of what looked to be art related object. There was a small terra cotta effigy, a tiny statue of a warrior, part of a bronze something-or-other (maybe a mechanical arm?), what looked like an outside armature for a clock, a marble or stone thingamajig, a few drawings (colored and black and white) and a couple of smaller paintings (mostly unframed). As I went through this stuff, I realized that had happened upon the art her strange form of kleptomania had impelled her to pilfer so regularly. It was a rather disconcerting discovery. And though I could sort of imagine where some of them came from, about the rest I was clueless. And I was surprised she didn’t put these trophies on display or arrange them triumphantly on a shelf, but had stashed them away in a bedroom dresser. Anyway, I put the objects back carefully and moved the piece of the furniture back to where I had found it. As I fell back asleep I decided not to mention it, ever.

When Luisa passed away several years later from a sudden and virulent tumor, I wondered what would become of her secret stolen art collection. Would whoever in her family that was straightening her place up even know what that stuff was? I suspected that it would all be gathered up and thrown away. I thought about writing them to explain what the stuff was, maybe asking them to try and give it all back, but then realized I didn’t know who to write or how to explain or even what to say to them. On the day of her funeral, I almost stole a small candleholder from the prayer offering altar in the church but, in the end, I didn’t.

What is preserved in preserves? Might it be an essence or could it be a single element; it is generally a distillation or decantation. The process of preserving maintains a specific but tenuous connection with its source, in Joan Tanner’s work. Her things abscond with only a slight trace of their origins; the sense of whence they hail from is by and large occluded, often baffling and can even turn slightly vexing. Their joyful insouciance doesn’t seem proper or appropriate every time. Maybe it is precisely that which turns our pleasure from passively observing some thing as a benign albeit odd mass into actively worrying about viewing the same thing as unsettling or possibly troublesome quanta that she is working up. We cannot settle on any one relationship and just enjoy our quandary at length. We seem to yearn for reconstructing a genesis, levying a judgment, formulating a cause. Yes? No?

The impact of these things in that arrangement on the mind’s eye is mildly jarring. Circling them, perusing the numerous and logically inconclusive connections between the elements and then darting in and out of semi-certainty about what the configuration is doing or was doing or could be doing sets off conflicting flights of fancy. Is this an abandoned test site (already spent) or is it a future experimental site (gearing up)? Could it be a random placement. These things might have just ended up this way by chance and yet we want to make sense of the arrangement. The gossamer is wed to the sticky, the twig-like is bound to the brittle and the delicate is partnered with the coarse: all in the name of a gambit that necessarily unshackles the power of seeing things, through and through and through.

Joan Tanner has an uncanny ability to resuscitate even the most unlikely fragments and cast-offs. She turns them into powerful poetic means for seeing things in the world with entirely fresh eyes. Understanding is arched and bent into an entirely new standing and perception is turned into a means for innovating, not only for marking off the already known or the quasi remembered.

When I was a teenager and we moved from the states to Italy, it was like the whole house got turned on its end and dumped out into the backyard. Stuff came out of hiding, things were unearthed, junk resurfaced. From behind the wall in my bedroom above the garage where I had made a clandestine hidey-hole years before, a crumpled notebook emerged. It was almost illegible due to a slight film of dried mold and brownish watermarks. It looked like it had been put there for a moment or so long ago and had just never made it back out. It wasn’t like I had never used that hiding place again, but I guess the notebook got pushed far enough to the back of the space and must have been slightly out of the reach, in a spot that was accessed rapidly and with as much stealth as possible. It wasn’t really good to be found lying on your stomach on the floor of your room staring at the floorboards, even in a time of psychedelic consciousness-raising and long sustained bouts of musical enrapture.

This notebook, I discovered, contained many embarrassing written fragments of a distant past life (3 years for a teenager is like an eon). There were annotations on how I had once found my way to an open telephone call line by calling my own phone number and then speaking between the busy signal to a collective of unknowns. There I had the temerity to tell these strangers what I was really thinking and feeling, only to discover that I had confessed a crush on a girl at my school who was unbelievably in on that same call line. Not only she was a year older than me and a cheerleader – so from an entirely different universe – we were also in the same advanced math class together. My confession gained me a school-wide notoriety that I would have gladly done without. Fortunately, I would be leaving the country soon and wouldn’t have to keep dealing with the repercussions in High school. Other humiliating and inopportune events were recorded in the distressed little paper volume, still legible, in spite of the wear.

So I made a gesture that would become a leitmotif of mine for many years to come: I went and built a small fire and burned the booklet one page at a time. As the pages darkened, curled and erupted in flames, I took solace in the destruction and even felt relieved that proof of my impossibly inopportune existence was now being eliminated. If I could go back in time, I probably would put out many of the fires I set and the bonfires I built when things got larger. I would be tempted to preserve the many notebooks and objects shed, burnt or shredded over the years...

Past pendulums aside, the side-to-side sway is the dancing point. And it is the why to track the way the mass pushes down and away and out and how the inflections and lighter intrusions anchor, buoy and influence how the danglings evolve. Much like the language tethers thrown to loop this whorl of work in, on the whole. On the whole I admire Joan Tanner’s will to straddle the impossibility of making an absolute choice between discarding an awkward and even discomforting past or relying on the precarious less visible instability of the present. The truth resides somewhere in between and definitely in tension. Maybe that is why her art gives me so much pleasure and why I want to see it and revel in her creations over and over again. Tanner’s work under- and over- stands in for those unfindable or hereto dispatched things; restoring, if not the things themselves, the paradoxical power of their objecthood for us and our memory.