Reviewed May 1, 2014 by Karen An-hwei Lee.

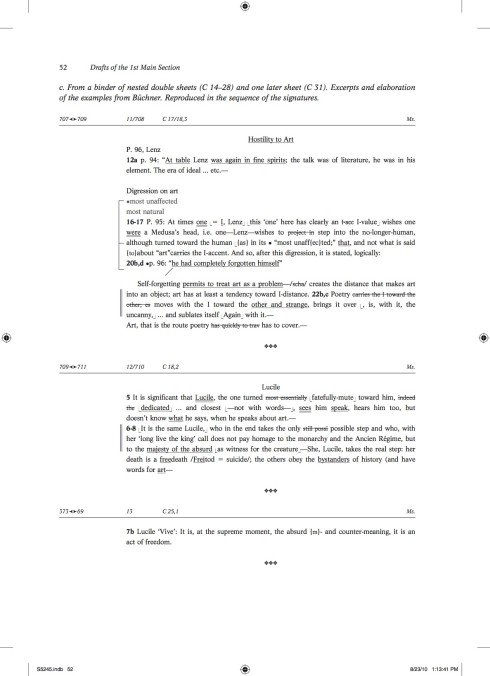

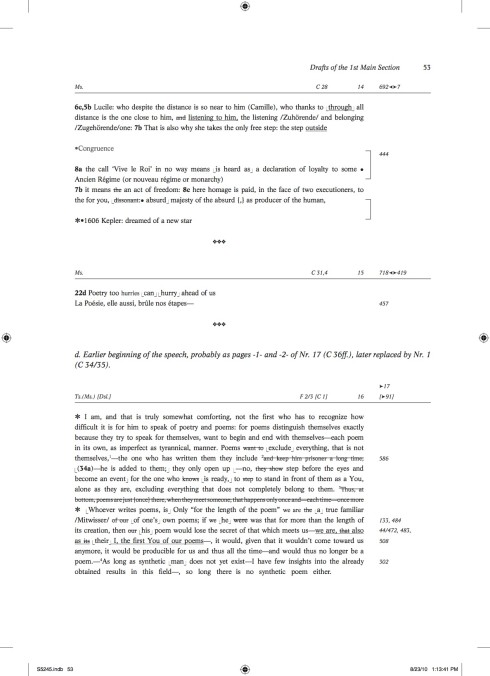

Seven years ago, Pierre Joris – beloved Celan sage and NOET father of nomadic poetics – took on the formidable task of rendering The Meridian and its edited transcripts from German into English. To say in the least, the issues Joris faced while translating The Meridian were multifarious, namely, “the difficulties of trying to render minute differences between four or more parallel German versions or drafts, while staying true to and rendering the typographical layout of the original transcriptions.” Such a vigilant transcription duly amplifies our readings of this celebrated speech. In these exemplary revisions, note Celan’s fine-tuned ideas on poetry and authorship in three versions:

Poems want to exclude everything they are not by themselves, – the one who has written them they include and keep captive for a long time; – he is added to it;

The poem is lonely and en route. But stands is, here already, in the encounter—in the mystery of the encounter.

The poem is lonely. It is lonely and en route. Its author remains added to it.

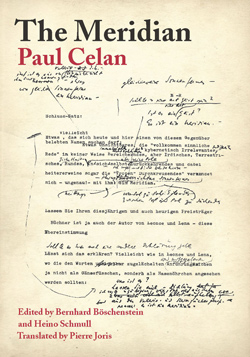

The Meridian was originally delivered in 1960 by Paul Celan at the festivities for the Büchner Prize in literature. As heralded by Stanford University Press, “It is a meditation on the state of poetry and art in general and a rigorous attempt to account for what poetry is, can, and must be after the Holocaust.” This past December, Joris’ translation of The Meridian – Final Version – Drafts – Materials won the Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Prize for a Translation of a Scholarly Study of Literature, awarded every second year by the Modern Language Association. I had the pleasure of acquiring this volume of paleographic treasures at the 2014 MLA Convention in Chicago.

The German edition of The Meridian includes, as the subtitle indicates, the final version, its drafts, and preparatory materials, a consummate monograph of sundry Celan archival gems. Bernard Böschenstein and Heino Schmull – the German co-editors – aimed diligently to preserve the diachronic transparency of Celan’s evolving drafts.

In Joris’ own words translating The Meridian, “These scholarly transcriptions of all the extant textual variants of Celan’s Meridian speech include a complex apparatus to reproduce deletions, inserts, additions, and a further range of miniscule changes (capital to lower case, vice versa, etc.) which I tried to maintain as closely as possible in the English.” Thanks to Joris’ persevering dedication to this Sisyphean labor, the drafts and preparatory materials are now available to Anglophone readers, a process reflected in Celan’s remarks on the open-ended journey of artistic inspiration, locating the poem as a seeker of “a place” outside time:

When we speak with things in this way, we are also always confronted with the question of their where-from and where-to: a question that ‘ stays open,’ ‘does not come to an end,’ that points toward the open, empty and free – we are far outside. / The poem, I believe, searches for this place too.”

In this excerpt from an early draft, the comments after the asterisk never surface again in subsequent versions. To this end, the transcription captures a fragment of text unique to this draft, amplifying Celan’s thoughts on phenomenological relations of poetry, “last things,” and the nature of time:

When we talk in this way with things, we are always also at the question of their where-from and where-to: at a question that “stays open,” “does not come to an end,” that points toward the open, empty and free—we are far outside: * every strange time is other than ours; we are far outside, but in any case only at the edge of our own time; the perceived things are also there with us: they stand there where we stand at last: the things in the poem somehow partake of such “last” things could be, one never knows, the “last” things.

General readers puzzled by The Meridian’s allusions to iambic puppets, an abyss and automatons, a monkey, and Medusa’s head may look up these references to German playwright Georg Büchner by using an easily navigable Appendix: “puppet-like, imabically five-footed […] a childless being: cf. Camille’s monologue in George Büchner’s ‘Danton’s Death,’ cAct 2, Scene 3, ‘A room’ . . . .” Editing the drafts of The Meridian involved a scrupulous transcription process which Joris has, in turn, meticulously translated into English. In addition to the final version of the speech, the volume includes drafts in preliminary stages, various notes and preparatory materials, a glossary of typographical labels and special characters, and a fragmentary meditation on the poetry of Osip Mandelstam:

9 2. Speaker: Osip Mandelstam’s poem wants to develop what can be perceived and reached with the help of language and make it actual in its truth. In this sense we are permitted to understand this poet’s “Acmeism” as a language that has borne fruit.

10 1. Speaker: These poems are the poems of someone who is perceptive and attentive, someone turned towards what becomes visible, someone addressing and questioning: these poems are a conversation. In the space of this conversation the addressed constitutes itself, becomes present, gathers itself around the I that addresses and names it. But the addressed, through naming, as it were, becomes a you, brings its otherness and strangeness into this present. Yet even in the here and now of th epoem, even in this immediacy and nearness it lets its distance have its say too, it guards what is most its own: its time.

11 2. Speaker: It is this tension of the times, between its own and the foreign, which lends that pained-mute vibrato to a Mandelstam poem by which we recognize it. (This vibrato is everywhere: in the interval between the words and the stanza, in the “courtyards” where rhymes and assonances stand, in the punctuation. All this has semantic relevance.) Things come together, yet even in this togetherness the question of their Wherefrom and Whereto resounds – a question that “remains open,” that “does not come to any conclusion,” and points to the open and occupiable, into the empty and the free.

Marvelously, Celan’s extensive notes and materials often read like miniaturist poems or aphorisms. Take, for instance, this sentence floating on the back page of the last sheet of Typescript A: “When your breath grows through it, you are given over to your poem.” Or consider this brief meditation on a poem’s relationship to language and speaker, pulled from Celan’s posthumous writings:

language as the language of the one who speaks //

the one who speaks as the speaker of the language =

in this antinomy – without synthesis – stands the poem.

Or these jewels on pages 103 through 152:

There is ‘a poem in the poem:’ it is in each wordfiber, in each internal

Breath:

The poem remains, if you allow me a little critical jargon, pneumatically touchable.here on breathroutes, the poem moves =

Kafka: to be, not to have (language = to have)

To write poems: a beginning without allusion.

Lyric poetry is no longer a heuristics

To write poems: a beginning without illusion.

The poet as person is given to the poem as its share –

The poet’s being-directed-toward language /Auf-dieSprache-Gerichtetsein/

(being-inclined)?

Of inestimable value to Celan scholars and avid fans alike, this well-edited volume far transcends an exercise in paleographic arcana – it illuminates the elaborate process and development of Celan’s trajectory for The Meridian in the larger context of his oeuvre, and the role of poetry and art in the modern world after the genocides of World War II. A literary archaeological excavation, the palimpsests of writing erased by our millennial technologies are exposed in handwritten and typescript pages – a spectrum of tender insights on his own oeuvre – as in honest reflections on his famous “Todesfugue”:

Death Fugue

reaons to regret it – but one writes incurs and calls up that too.

The temporality of writing and its intimate nature – Celan’s thread-like handwritten pages, notes to himself in blue ballpoint, black water-based ink, pencil, blue and red crayon, arrows, circles and squares around words, innovative punctuation, carets, and other marginalia – come to light in the facsimiles of original documents and transcriptions.

Remembrance – anamnesis etc.

Speechspaces

The poem has time and has no time.

I relished the synchronicity of drafts of The Meridian in parallel columns – a profusion of elisions, insertions, and expansive annotations. “Poetry can mean a breathturn,” a succinct clause present in one draft, is absent in another, while the following notes on p. 34 appear distilled in the final version on p. 9:

The poem gives itself into the hand of the one, you, who stands in therewith in the mystery of the encounter – into what hand does it give itself! It gives itself into your hand? By the most strange illuminated as if it were its own!

But doesn’t the poem therefore already at its inception stand in

the encounter – in the mystery of the encounter?

As a whole, this book of painstakingly transcribed – then translated – trove of Celan artifacts offers us a valuable cache of ars poetica inklings, a splendid constellation of Celan’s musings on language and modern existence: How suffering may find a voice through survival and human witness, and ultimately, not whether to write poetry after genocide, but rather, how and where the poem exists in historical time and how poets can write in face of the brutal forces of annihilation – that is to say, given an altered correlation to the exalted soul-flight of the Romantic lyric versus nihilistic Modernism – how to persist in the soul-art of poiesis even in the tongue of the oppressor, in this case, German. On an even brighter note, my appreciation for Joris’ arduous seven-year translation project concludes with Celan’s own insights on translation as an act of faith – “the leap” – as noted for Breathturn:

The translation of poems is an exercise in this sense: it happens across the abysses of the languages: what unifies is the leap. – Such a leap is happiness and success –