Reviewed August 1, 2015 by Savannah Ganster.

On Language, Oppression, and Violence

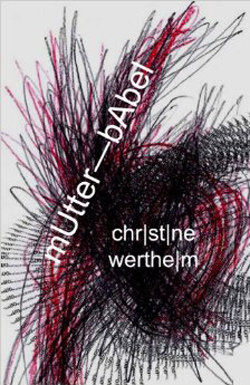

In her book, mUtter—bAbel, poet Christine Wertheim invites the reader to enter a world where the violence of language, birth, labor, and genocide are explored. She begins with personal violence done to the body through the labor and birth of a child, before moving to consider the oppressive and violent nature of language acquisition for that child. The text then considers specific accounts of genocide, which Wertheim relates back to the political power/powerlessness of people as established by and through language. Finally, Wertheim addresses the topic of death, which allows the arc of life from birth to death to exist easily within her work. The 148 pages of poetry, published by Counterpath, is a unified work spanning six chapters with a short “Interlude,” wherein the main question of this text is posed. Wertheim writes:

The question addressed in this text is:

how does the nO|sy sh|tty SwOund

of the unbearable and inconsistent hOwle

manifest in adult life, particularly when

this Obscene verabge [sic.]

is related to the caregivers and their

vO|dse?

This is the question she seeks to answer at the book’s start through the experience of the mother giving birth to the child and teaching it / “smOthering” it with language. She explores the inconsistencies of and dissatisfaction with language, and the violence that accompanies that dissatisfaction as a result. Wertheim notes that this is

the story

of degeneration in

the mOther’s vOcal Organs

is thus also a tale of

d|s-Organization

within the

child’s own body.

Moreover, throughout her book, Wertheim also demonstrates the violence that is done by and to her own voice by switching between voices. Her careful navigation of the slippages of language, the overlapping of voices (the voice of the mother, the voice of the child, the voice of the critic, the voice of the academic, and the voice of the advocate), and the oppressive nature of imposed language create a book filled with unique tensions that call attention to the main question of the text through the experience of reading and making sense of the words in relation with one another as they are laid out on the page. Ultimately, Wertheim’s explores the acquisition/imposition of language on a child by its mother, which she views as violent and oppressive. She writes, “it is a story of hOrror / of when wOrds become Obscene.” The language presented to/pushed upon the child is made manifest as oppressive “nO|sy sh|tty SwOunds” representative of a disorganization or degeneration of the body of both the mother and the child, culminating in violent struggles of power and powerlessness in adult life.

Situating language, and the majority of this text, in the body gives Wertheim the opportunity to make concrete poetry of the language of oppression. She writes the text of childbirth in overlapping lines of red text to create the image of a vulva and images of a birth canal, the modulating lines of a child’s cries are written in wavy black text, the circular breaths of the mother breathing through the labor are created as round erasures in the heavy red text of childbirth, which is reminiscent of blood. The repetitive nature of the text, overlapped with itself, illustrates the difficulty of childbirth, and the pain of the labor through the imagery it creates, and through the laboriousness of the reading. The red text flows through the pages of the first chapter as though it were blood pouring from the mother, as she breathes through the pain, knowing that “s/he’s cUm|n’.” The sounds of the childbirth, the moaning and cries are caught up in text running across the pages, “nnnnnnnnnnnnng haaaaaaaaaRRRRuuuuuuurrrr,” and “aaaaaaaRRRRuuuuuuuurrrr,” that are populated with the images of childbirth created by the overlapping of the textual lines that read, “th|’sOng’s of the-m-any-Others’flow-er-ingvO|dSe,” which translates to “this song’s of the many others’ flowering voids/voices.” The chaos of the images and words on the page grows as the labor continues and the child is born.

After the birth, the child finally breathes, and begins to learn its mother’s tongue. Wertheim writes at the beginning of “Chapter 2: mUtters ’n bAbels,” that “it is the story of a body invited into language by its mOther’s vOice.” The child delights in the sounds of its mother, in the sounds it learns to make. The pages are populated by long lines of the letters “m” and “u” strung together to eventually form the word “mum,” the text occasionally marred by thin red or black scribbles. The acquisition of language by the child, prompted by the mother, is

call and response

response and call

mUtter and bAbel

playin’ in

the vO|ce.

It becomes more intense, more abstract with the text of the mother intermingling and at times penetrating the text of the child. The red, white, and black images drawn over the words, or drawn with the text suggest a saturation of language has been reached, and then a disruption occurs. Wertheim includes an excerpt from a letter by Vincent Dachy here, which reads: “[For] there is also dissatisfaction and the difference between satisfaction, care and respect (separation) aren’t given either…. The mother is not paradise and the position is particularly open to ‘confusion and excess.’” It is at this point that the mutter and babbling of childhood language acquisition gives way into a more sinister oppression of language as noise. Wertheim writes,

it is the story of a child getting stuck

when |t feels |ts mOther’s vO|ce

turn from an invitation

to an imposition.

As the poem progresses, the pages become more cluttered with handwritten letters, redactions, enlarged “O”s, scribbles, and black and red hand drawn shapes. The chaos of the spatial layout increases, as does the poet’s use of the words, “nOth|ng,” “nO,” and “nO|Se.” The repetition of the noise on the page increases to a howl, oppresses the child and the reader, begins to slip between words and sound, between words and other words, exists in excess. Wertheim notes, “what was once a pleasure / is now unbearable.” This shift from pleasure to the unbearable is a shift from desire to disgust. The language of the mother imposes itself on the child in such a way that it is no longer enjoyable for either the mother or the child. The words continue to grow more repetitive and more oppressive. “Voice” slips into “vo|dse” while “hOwl” slips into “hOle.” The violence of the language, the violence done to the language, and the violence done by the language grow as the poem continues toward its climax. Wertheim writes:

this is the child’s sense

of a degeneration within

the mOther’s vOcal Organs

the mOther as chOra-s

the mOther as hymen

the mother as vO|ce

the mOther as mUtter

the mOther as tOngue

the mOther as nO|se

the mOther as hOwle

the mOther as swOUnd

the mOther as vO|dse

the mOther as mOUth

the mOther as Orifice

the mOther as hOle

the mOther as sh|t-hOle

sh|t-vO|ce, sh|t-vO|ds

sh|t-wO|ds/ sh|t-wOrds.

She clearly and methodically lays out the slippages of words into other words, before moving into a critical, academic voice on the next page to delivery a very expository set of verses. Wertheim suggests that each person must negotiate the language of their caregiver and of themselves in such a way as to pass “between the satisfaction + dissatisfactions.” It is this shift into the critical, academic voice that marks the shift to the final section of the book, where the truest violence occurs.

In the “Interlude,” Wertheim’s critical, academic voice interrupts her poetic text. It is this voice that remains the most visible throughout the rest of her text, despite being intercut with the voices of the mother and the child. The author begins to consider the politics surrounding voice, language, violence, and power when she writes, “D|s-satisfaction is thus confused between the child’s demands of the mothers, and its perception of a demand coming from them. ‘This from/of indicates a crucial ambiguity around the Mother and her lack (of power) or powerlessness’ (VD).” From here, the text of Wertheim’s mUtter—bAbel moves to consider the powerlessness of so many Mexican people: the immigrants, the women, the factory workers, those living in Juárez, and the dead. The implications of language as a mode of oppression are clear, as she moves seamlessly between prose about the state of Mexico, complete with statistics, and the voice of the child. The typography culminates in chaotic chatter, the mashing up of multiple voices as they overlap one another: statistics about the death rate in Juárez, talk of violence and killing, and shitting from the mouth.

Finally, Wertheim shifts entirely to the topic of death, the opposite of the birth with which she began her text. She considers the genocide occurring in Uganda, considers the use of language, the use of the mouth, writes of biting a girl to death, considers colonization and the oppressiveness of language. Her academic voice cites statistics: “In 2009, 2,753 were killed in Juarez. This year, [2010] as of May 18th, 973 had been slaughtered—a 60% increase over the same period in 2008.” Her advocate voice calls for our attention: “We Westerners have a tendency to see African conflicts in purely humanitarian terms. But mass displacement in northern Uganda is primarily a political and legal issue because the Acholi were intentionally displaced by the Ugandan government.” The child still speaks, but less frequently. The mother’s voice has been almost completely silent. Wertheim writes of death, of being unable to breathe, a counter to the child who breathes in the Chapter One. In one of the final lines of text in this book, Wertheim pleads for westerners to

let THEM [the Acholi people of Uganda] breathe

breaaaathhee

breeaatthhe

the breaking of her

breaaatthhe.

It is this act of breathing, followed by the shushing on the final page of text that suggests that in order to move away from the violence and oppression created by and through language, silence is sometimes needed.

Wertheim’s mUtter—bAbel triumphs in its consideration of language as nurturing and desirable, while simultaneously being oppressive, violent, and disgusting. Her arc of birth to death yields various types of violence for consideration, from the violence of the labor and delivery of a child, to the violence of the Mexican drug cartels and the Ugandan genocide. Violence permeates our words and our world from birth to death, in the realms of the personal, the public, and the political, and Wertheim captures this violence clearly in the language and layout of her poetry. The use of various voices creates tensions that work to push forward the poetry in creative ways. Ultimately, Wertheim’s text, while difficult to read at times, creates a rewarding experience for the reader by allowing the reader to be simultaneously oppressed and liberated by the poet’s language.