Reviewed October 1, 2014 by Sharon Mesmer.

Girl bag. V-able slag hole. Sticky ultrapocket. Raw zone. Rosy patoot. Swollen sack of piggy laters. Muscular tunnel replete with mucoid protein. Contraction machine. Rag hole. Cutty pie. Pudge.

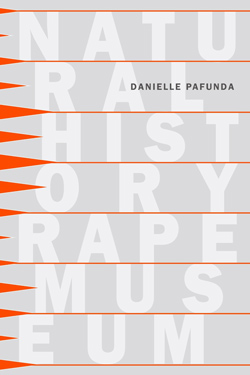

No good euphemism for female reproductive parts is left unturned in Danielle Pafunda’s Natural History Rape Musuem, which begins with an uttering of the ding an sich: “When they called me vagina.” No — on second thought, Pafunda’s book begins with the title, where each word functions like the elements of a haiku:

Natural

History

Rape

Museum

Each of those elements trails clouds of associative glory when considered separately. But when viewed as a kind of a “process haiku” where the last word assimilates properties of the previous three and bodies forth a transformed meaning, that final word truly has (and is) the last word. For what is the final stop for “natural” and “history” but “museum”? As for “rape,” it functions here as it does in women’s lives: as a severing, a cutting. And in haiku there is also a severance that occurs when two juxtaposed images are interpolated by a “kireji” (“cutting”) word. Here, that severance changes the manner by which the more ordinary elements were previously considered. And throughout the collection rape disallows ordinary experience by creating an event horizon that is an abyss of mothballs: rape / natural; rape / history; rape / museum. The sardonic voice of the female narrator — who speaks not as an individual but as a multiplicity of women distilled to an orating singularity — speaks against this forgetfulness:

My middle face banished, homo sacer, neither sacrifice nor dead meat. A mother mask was stitched to my / raw zone. It was a mistake, but it was not wholly successful.

Intimately involved with all this is the fuckwad, the collection’s male antagonist/adversary/hideous helpmeet. He is first named in the first line of the third poem (“The fuckwad wants to know why she’s bothering to dress/like a lady”), and inflects the action of every poem, even the ones in which he does not appear. His role is voiced by the collection’s multiple narrators . . .

The fuckwad brings a sarcastic remark to dinner.

The fuckwad says: My muckle of muff the umbrella-headed guinea fowl. She eats not, she wants not, she shad me.

The fuckwad has placed her in the room with the knife … Watch her pollywog doing.

. . . but is clarified in the final poem, which is part of a section of four related prose-poem essays on pain that close the collection:

His teat slammed in the door will give him away. His brow pimpled with exposure. He hangs on the world with all twenty brittle nails, yellow, fungal, earthy. He hisses a carbon sack that damps the room. His files are on display in the Natural History Rape Museum. Alongside his death mask, cast in plaster, his mate pumped full of plaster. His sweetmeat detailed on the program, a chorus of.

He is both captor and prisoner, and he and the narrator(s) share a twisted, fated parity that is both physical (“his teat”) and psychological. He keeps her/them boxed-in:

The fuckwad says: My dear, my doughy dewy doe-eyed dimple, you mustn’t attempt to think while you sphinx.

And this box is an actual thing, it exists on the page and resembles a fortune cookie containing the titles of many of the poems, which likewise function as haiku:

The man in your life

will exercise his fink

till it wail

When you lie down you get

up again and there are fleas

as well as bedbugs

Pafunda’s words carom off each other in a process of becoming, and in not unfunny ways, despite the seriousness of the context:

But the fuckwad sings it: I’d rather itch my scratch

than bed down the cur/b

A ml of Botox wrote an entry in a pink diary locked with a pink plastic key. The diary contained twenty-eight blisters. Only one blister was marked. The ml of Botox claimed an advantage over other compositions. It claimed that it alone could produce that endless series of inexpressions, each of which would correspond to an inarticulable synaptic disaster.

This particular section of “The Manner In Which Pain Becomes Me,” the preantepenultimate poem of the collection (part of the series on pain), reinforces the subtle thread of humor that courses through the book. Pafunda is funny as she cathects the surreal qualities of situations involving the clueless fuckwad, but soon her humor moves to a deadly seriousness that introduces new avenues to violence:

Sings it high, the old tune, the fuckwad, humming, French

and bawd, humming, This the bitch who waits on the rug,

fire-spooked, slipper-gagged, this the old bitch who keeps

her head, bears her head and broods.

This simple unknowingness that culminates in a dangerous ignorance (which William Blake termed “unorganized innocence” — the thing that, historically, has always gotten us in trouble) is a kind of foundational attitude throughout the book. Pafunda objectifies this attitude in her use of the boxed, haiku-like text and their matched, bracketed titles in the table of contents (for sections one and four). There are also empty title brackets in the TOC denoting the final poems for first, second and third sections which are not picked up in the actual text; these seem to suggest the nonexistence of the female narrator(s) in the ken of the fuckwad — perhaps the most prominent quality of his “unorganized innocence.”

The third section of the book is a “cutting” as well, severing the first and second related sections from each other, and suggesting the denial of continuity that rape imposes. Here, a series of odd totems is explored, among them a wolf spider, which concludes the morphing trope of dog/wolf begun in the first section:

The fuckwad’s translating again: She the dog pets it,

she the dog it pet.

Feeds it with a supper,

she the dog walks on a leash

She the dog found by the brook . . .

(Note that boxed text cuts each of the above lines, except for the first, in half.)

Dog the wolf with teeth from the junker.

Dog the wolf with headful of pace.

Wolfing up on the rag rug, filed to its singular risk.

The tip of its species, and the shiv of the world.

“Bitch” is, of course, the inferred association for “she the dog,” but Pafunda is more wisely committed to the music of the lines, and so the long e of “she” echoes “feeds” and “leash” and brings in the association without the heavy-handedness of explanation.

Most importantly, Pafunda provides for rape a “vocalise” (pronounced with a long “e” and connoting the wordless female choruses of male composers like Debussy and Holst) which is more a texture of pain than an actual language, sound being the truest response to certain experiences, especially the grotesque. Further, the poet brings something way ancient and very female to the party: there was a genre of ancient Greek poetry marked by scurrilous language, humorous invective, insult and even abuse (αἰσχρολογία, aischrologia = “shameful language”). This type of poetry, sometimes referred to as “blame poetry,” evinced ties with Old Comedy (e.g., Aristophanes’s “The Frogs” and “Lysistrata”), and appears in Horace’s epodes and satires, though the Latin poet is actually riffing on the Greek poet Archilochus, referred to by scholars as “the archetypal poet of blame.” But being Don Rickles in a toga (or chiton) was not just a fun thing to do around the agora, though one of the functions of this poetry was, indeed, to entertain and/or extract delicious personal revenge. The purveyors of blame poetry were pointing a finger at ignorance, the “unorganized innocence” of non-heroes (= fuckwads of the Classical Period), for a sympathetic audience. And most interestingly, the nine-day festival of Demeter and Persephone — commemorating Demeter’s search for and retrieval of her daughter from the Underworld — commonly referred to as the Eleusinian Mysteries, is where this type of poetry is believed, by scholars (who were themselves often the subjects/targets of the poems), to have originated. Among the various activities during those nine days was ritualized obscene language. This is because a bawdy female character who appears in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter hurls a stream of invective so abusive, sexualized and insulting (girl bag … v-able slag hole … rosy patoot … swollen sack of piggy laters … rag hole … ) at the aggrieved goddess that she is shocked into laughter. This character’s name was Iambe, and it is, in part, from her potty mouth that the “blame poetry” genre — formally called Iambus — originates, as well as the metrical foot called iambic, considered by those old poets to be the most fitting foot for lampooning humor. Thus Pafunda reminds us that Comedy and Poetry share a natural history, a history sorely in need of redemption from its abyss of mothballs.