Reviewed May 1, 2014 by Benjamin Landry.

Spirit Lines: The Poetry of Incompletion

For years, now, I have been haunted by a vision of a not-yet-rendered portrait painting. I cannot say whether the subject is male or female, clothed or nude, neither can I name the artist. Suffice to say it is a fully realized and expressive likeness that incorporates an unfinished fleck of raw canvas at the reflection point of each eye. That the punctum is a perfectly planned element of incompletion, un-painting, speaks to my predilection for poetry that is animated by the inexpressible regions of human experience, those emotions and memories that are on the tip of the tongue and which necessarily draw us beyond our current understanding. This is not quotable poetry: it eschews aphorism and convenient revelation. Conversely, it is not “unfinished” poetry, exactly. Rather, it is poetry that honestly admits the inchoate, affirms mystery and responds to successive readings: it is alive.

Incompletion as a compositional technique assumes many forms, from the straightforward thematic ambivalence of some of Emily Dickinson’s best poems to the rhetorical incompletion of the posed and unanswered/unanswerable question. In discussions of prosody, we speak of poems which either “close down” or “open up,” but this distinction hinges on a narrative development that implies its opposite as the prevailing condition. Poems that function by incompletion are open throughout. In the preface to The Gorgeous Nothings, Susan Howe describes Dickinson’s envelope poems as “unbounded and contingent,” and asks, “Is there an unwritable unknown poem that exceeds anything the technique of writing can do?” Poems of incompletion do not answer this question; rather, they provide glimpses of the working mechanism. This is what animates the unlineated title poem, one of many possible readings of which I’ve assembled here:

Afternoon and / the West and / the gorgeous / nothings / which / compose / the / sunset / keep / their high / Appointment / clogged / only with / Music, like / the Wheels of / Birds

The poem is written on a collage of three scraps of paper and must be turned and readjusted to be read. It is a motion that concretizes the “Wheels of Birds,” encouraging our successive passes at comprehending the “gorgeous nothings” (daydreams? seraphs? colors? atoms? sounds?).

In the work of Cole Swensen, incompletion is both thematic and stylistic, taking the form of gaps between sentence fragments, windows in the text. Her recent Gravesend is an exploration of the occurrence and nature of ghosts, as revealed by later-fictionalized interviews with the inhabitants of Gravesend, England. A recurring theme for Swensen is the historical relocation of haunting from personal to collective spheres, as, with the advent of the ghost story genre, “ghosts became strangers.” This estrangement, in which encounters even with ghosts known to us conform with familiar narratives of horror, benevolent intercession, etc., represents a diminution that Gravesend intends to address. One might suppose, then, that the gaps between fragments simply make literal this dislocation. The collection’s first poem, “Echo Body,” gives us the following arrangement:

[…] if a man closed his hand, you’d

call it a fist, but that was not the fence immense, the single note

upon note that breaks in the sun because what walked on […]

Elsewhere, Swensen has claimed that she does not work by erasure, that the gaps do not represent portions of the poem that have been effaced from a cohesive whole. As the above example makes clear, the narrative sense either bridges the gap (“if a man closed his hand”) or is obliterated by it (“but that was not the fence immense”). The gaps, then, stalk the sense. They are the determining factor, the stand-in for the poet’s hand, rearranging, allowing or thwarting connections. Often, the gaps allow a transition between registers, as Swensen tacks between the raw materials of her interviews, meta-commentary and a productive poetic digression. Or, they facilitate a proliferation of definitions of ghostliness, culled from various witnesses. As such, the gaps make room for provisional and contradictory experiences that end up forming a collective testimony.

Sometimes, Swensen’s gaps appear to serve no function in the poem. One conspicuous example is in the first of three poems entitled “Gravesend”: “[…] Did you fall off the edge // and which home carved from an egg […].” The “and which” is a syntactical pivot between two missing clauses. What’s going on, here? Swensen shows her hand a bit in “Interview Series I,” when she wonders, “Would you have thought that over 70% of these people who look so untroubled have ever seen anything that they couldn’t in any way explain?” In fact, her interlocutors are able to explain quite a bit about the ghosts they have seen, including the appearances, precursors, attendant sounds and motives of their ghosts. It becomes clear in the course of Gravesend that the unconvinced party is the speaker of these poems, rather than the interviewees. The “and which”—and stranded fragments like it throughout the collection—indicate that there is a poem written behind the poem, like the world of ghosts glimpsed only at erratic intervals in the world of the living, or as “sky between the trees.” Swensen’s speaker is willing to brave these mysteries in pursuit of the hidden poem—without promise of resolution.

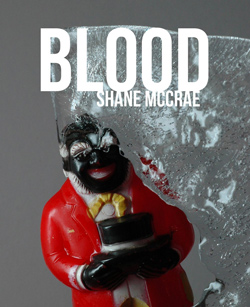

Swensen pursues the poetics of incompletion in relation to belief; Shane McCrae’s Blood pursues a similarly vexed project in confronting the horrors of slavery. It is precisely because the effects of slavery continue to echo past the completed historical fact that the poetics of incompletion work to his favor. Here, an indeterminacy of voice is often the work’s propellant. “Heads,” a narrative of the largest American slave revolt, begins:

1. Escaped into the Swamp Then Made His Way Back to His Plantation

500 men in uniforms in army

uniforms 500 slaves /500

niggers we happy we nigger

soldiers marched on New Orleans /And I was there I saw

after we niggers heads on sticks

500 men in stolen uniforms or only

some of us but everything

Even ourselves we touched our touch

made stolen even

our own bodies

The recursive “we” insists on agency as “soldiers,” but it also foreshadows the slave’s continual objectification and impending victimization (“we niggers heads on sticks”) at the hands of white slaveholders. In slavery’s dizzying pathology, for the slaves even to touch themselves, quickening into independent bodies, is to “lift” a good, commit theft. If the perspective is primarily that of a witness, escapee, it also implies the perspective of the pursuer, hence the repetitions of “500,” “uniforms,” “men,” “nigger,” “even” and “touch.” These echoes redound in an unending call-and-response of accumulating privations.

McCrae also employs incompletion as a means of highlighting the indeterminacy of familial allegiances. The issue is exacerbated by widespread sexual predation perpetrated by slaveholders on their slaves, and it results—for instance in “Brother,”—in siblings who struggle to recognize one another: “I can’t see in my skin our father’s face [notational line break] Brother or any other face / Of any like me brother the same black / Brother you got his skin or his but dark- / er.” The imagined dialogue between these brothers, who lack names to distinguish them apart, posits an unease exacerbated by the various proposed gradations—and parentages (the poem follows poems about the Garners, a slave family that includes a legitimate child and several illegitimate children—the progeny of slaveholder rape). How does a family cohere in such a historical morass? Should the love between children suffer for the facts of their births?

The questions McCrae raises through incompletion—an ambiguous voice—are ultimately impossible to resolve, and they are given clearest expression in the wrenching poems about Margaret Garner, the escaped slave who attempts the murder of her children rather than have them recaptured for a lifetime of slavery:

My first thought was My baby’s sick / Wasn’t a thought

really but that’s what all that blood / Felt like

but all that blood

Really but all that blood felt like my Mary getting / Sick on my hand

Wasn’t a thought my first thought was I wasn’t / Was I hadn’t but I couldn’t stop

After the first

Cut I couldn’t stop

because it hurt

The incomplete articulation of emotion mimics the terrifying ambivalence of a slave mother giving birth to a child who is—not legally—hers. The legal and emotional facts are so thoroughly at odds—on top of the dissonance of maternal bonding with the progeny of slaveholder rape—that it results in a fragmentation of the speaker’s identity (“was I wasn’t / Was I”) and a shocking act of violence fueled by simultaneous feelings of love, hatred, mercy and bitterness.

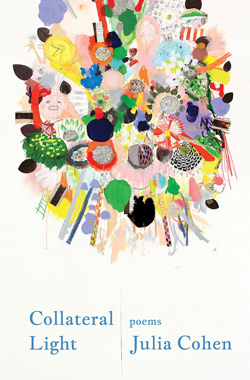

In Julia Cohen’s Collateral Light, a collection obsessively concerned with the present moment, incompletion manifests itself in continual fragmentation. As the speaker admits in “A Member of the Living Class,” “Some say I have little / faith in the full / sentence.” These poems read as proofs that value subjective experience far above any notion of objectivity. The uncertainty of such an existence is on display in “Fill Me with Poison!”:

[…]maybe you’re movement—

the kind that can look

back, stick an index

finger in an atom

nobility is not a feeling

cunning is not a feeling

decency is not a feeling

A feeling not an empty space

Here a localized wanting, a text

among animals & aprons

The raccoon makeup you’ll wipe

off to reconcile?

When objects lose their hold, abstractions step in to take their place. A “localized wanting” occupies the place formerly held by a “text.” Emotion reads like revealed truth, the actual self beneath the “raccoon makeup” that we take off in order to “reconcile.” Cohen’s poetry enacts the legacy of Dickinson’s abstractions, her “gorgeous nothings” in our own time, but there is something more ardently philosophical, more argumentative—which includes definition by ruling out alternatives—in Cohen’s approach, borne of the desire to convince her readership. Whereas Dickinson trusts that her reader will find a personal analog in the “gorgeous nothings,” Cohen revisits the notion of subjectivity from many different angles, somewhat nervously hoping that her view will take. This is not merely a question of brevity or authorial assurance. It is a difference necessitated by the demands of writing for a highly empirical contemporary readership resistant to notions of radical subjectivity.

To prove her point, Cohen records a number of seemingly disjunctive items and moments in “No One Told Me I Was the Arrow”:

A car will take

you away

Embryonic dish soap

& the also-sky

**

I caught

a life

of sea-

sickness

dreaming of ships

This quixotic monologue highlights the many instances in which causation is refuted—at least as often as it holds—in our lives. Is it possible to draw any further conclusions from such a poetry? I think yes, if we grant that poetry is as irreducible as personhood. Poetry like Cohen’s, for instance, endorses Barthes’s idea that the text happens at the interchange of the author, reader and cultural context. Or, as Cohen puts it in “Is It Hard to Count the Times I Am Deliberate?”:

I am visceral!

Just like you

The interplay

Just like paintings

The feelings

In this conception of subjectivity, oblivion is a companion to consciousness (“To pass by & ask ‘Will I remember / this?’ then later to remember only / the question?”). Intimacy is shadowed by the logical impossibility of a shared experience with any markers of objectivity.

Poets who incorporate incompletion in their work do so not to be difficult; rather, they record their experiences without shielding the reader because they think we can handle the same ambiguity in literature that we face in our lives. They distill experiences on the page, but they do not explain away the incongruities, the pain or the grace. The poem becomes merely half of a conversation, and a means for us to, in Cohen’s words, “worship doubt.” Spend enough time with poems like this, and one begins to feel that the neatly package truths one is often sold in more “popular” poetry are rather disingenuous.

In considering poetry of incompletion, I again return to the visual arts. In the room adjacent to my office hangs a small Navajo weaving I purchased some years ago at Two Grey Hills pueblo. The central design is a double-tipped arrow surrounded by repeating bird motifs in grey, brown, black and white. Look closely and you may discern a single brown thread running from the central design to the outside border. As it was explained to me, Navajo weavings incorporate these “spirit lines” as a means of allowing the weaver’s gift to survive the geometric rigors of a “finished” product. I like to think of poems that function by incompletion as being shot through with a “spirit line.” They are similarly “unbounded” and to be continued. We must not begrudge them their gifts.