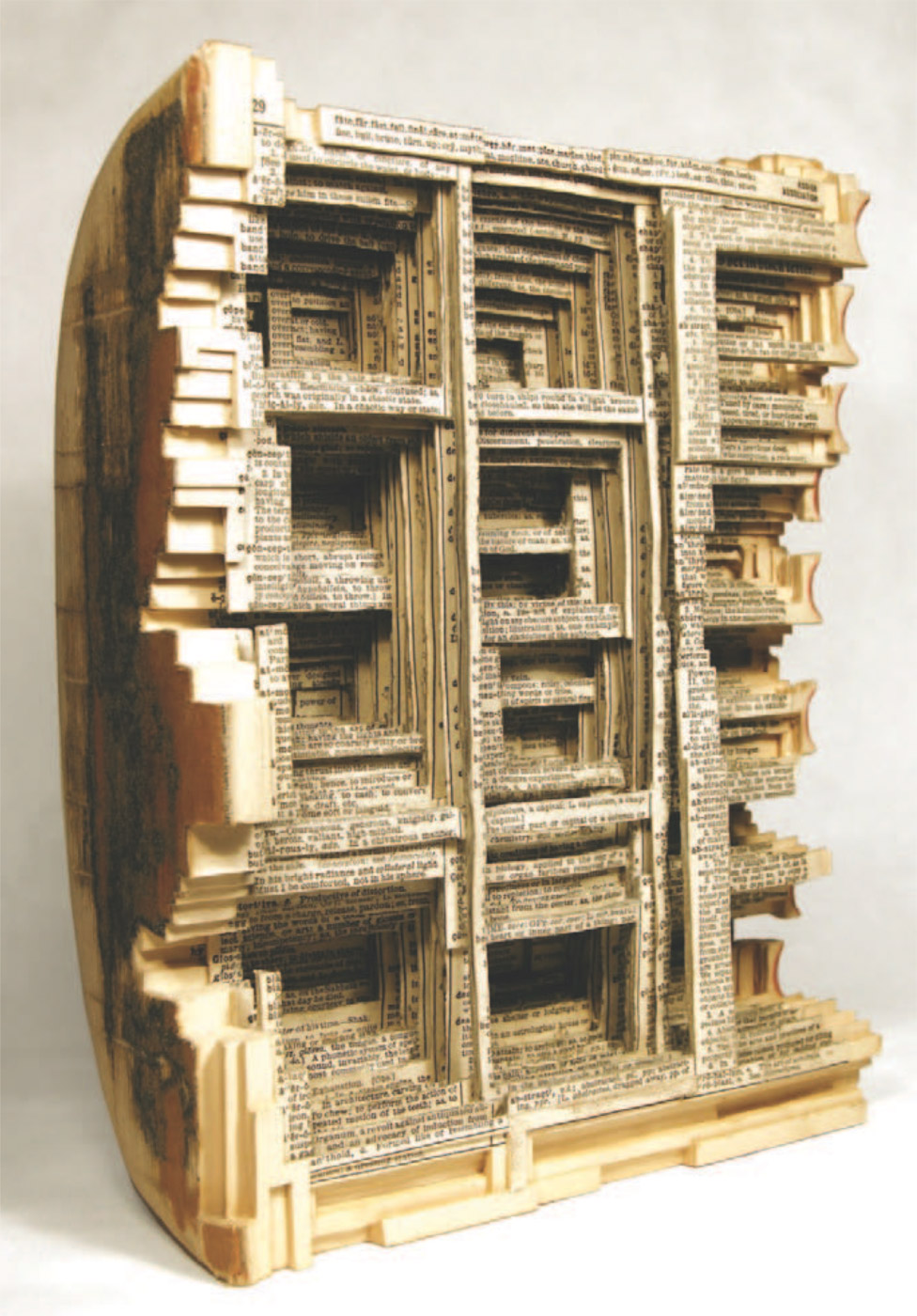

Brian Dettmer

Fate Far Fast Fall Final

At first glance, I found Brian Dettmer’s transformation of a book into dreamlike architecture hauntingly beautiful. It struck me as an ingenious materialization of the process of reading: the flatness of a page of words acquires depths and dimensions, just as the imagination takes flat text and creates multidimensional images in our heads.

At second glance, it struck me as a monstrosity.

But how predictable is that? I am a relic, a bibliophile to whom books are holy, intact bodies that ought not be desecrated. I would sooner pierce my sternum than cut into a book. But in this “visual poem” Brian Dettmer has cut open a living body and given us a carcass, a beautiful carcass, but a carcass.

On closer inspection, the book seems to be (or to have been, when it was alive) a dictionary. Which is fitting, because dictionaries may show best what is lost in the transition from books to files. In eviscerating this book, Dettmer has robbed someone of a poetic encounter with it directed only by the slipperiness of chance: of looking up jeroboam and finding je ne sais quoi, of feeling her eyes drawn to a drawing of an emu—an animal that, were it not on the same page as emprise, she would have forgotten exists.

The old dictionary is destroyed, but a new visual poem is created. So, I ask myself, does this destruction serve as a means to convey something unsuspected about the book as a form? In reading, we can hold a book open to only two pages at a time, which, as Roland Barthes wrote in S/Z, makes us cannon fodder for elaborate structures of desire for what is contained on the pages we can feel in our hands but can’t yet see. This desire-fraught blindness is imploded in Dettmer’s book, for suddenly, words from pages one might not have read to for many hours are visible at once, while the original “open” page is no longer legible. The book’s hierarchical structure—temporal or, in this case, alphabetical—is collapsed, even while, as through collage or erasure, a new spatial structure has come into existence. Even if it is a ruin, an X-acto-knifed Ephesus library.

So one could say that, as books start to disappear, Brian Dettmer’s dissection makes this book “appear” more than ever, reveals the relationship between time and space in a book that no screen can as yet replicate. Neither an X-acto knife nor time can (yet?) turn a PDF into a romantic ruin. Maybe Brian Dettmer, killer of books, kills them because he loves them too, too much.

Lately I keep hearing books characterized as white elephants that suddenly burden my friends and acquaintances, who feel weighed down by their sheer materiality. “I’m tired of lugging around all these books when I’m traveling,” one says. “I can’t wait to get rid of these bookshelves,” says another. What disloyalty! I think. Haven’t books always been there for you when you needed them? And now that they need you . . . ?

I know it is ridiculous, being the self-appointed defender and champion of inanimate objects. That is, if you see books as inanimate objects.

And I might have loved Brian Dettmer’s eviscerated ruin had the book been a priceless, irreplaceable antique. If it had been one of the forty-eight remaining exemplars of the Gutenberg Bible. The extremity of that violence would have been a fitting analogue to the violence of our collective indifference to the fate of the book.

On the other hand, maybe his transformation of the old dictionary into art gives it a dignified burial—a dignity one can only dream of for all those books on shelves around the world whose days, like our own, are numbered.