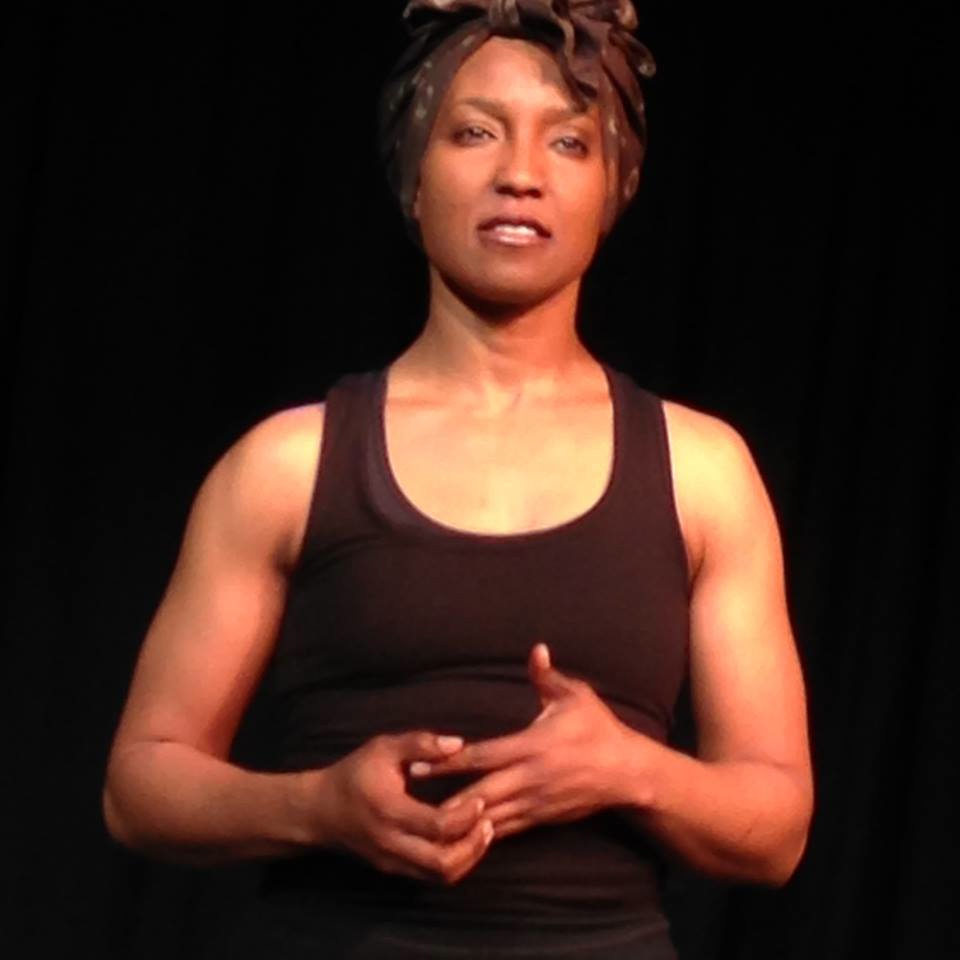

Duriel E. Harris as Sarah in Thingification, University of Missouri, Corner Playhouse, Feb 14, 2014, photo by Aliki Barnstone

The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized. This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are, until the poem, nameless and formless—about to be birthed, but already felt. That distillation of experience from which true poetry springs births thought as dream births concept, as feeling births idea, as knowledge births (precedes) understanding.

—Audre Lorde, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” Sister Outsider

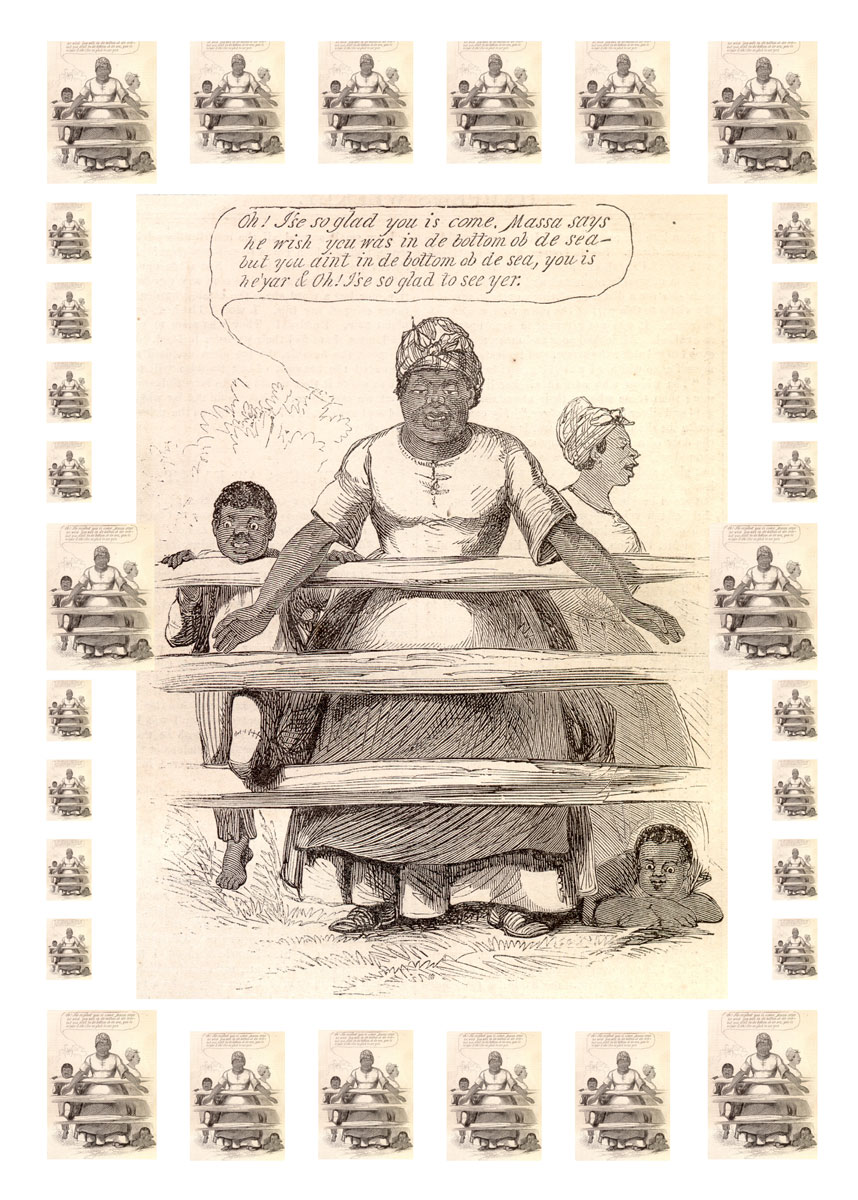

Our other picture illustrates a scene which we are told is very common in the States through which our armies have penetrated. The negro woman, hearing of the army’s approach, runs out to meet it, and cries: “Oh! I’se so glad you is come. Massa says he wish you was in de bottom ob de sea; but you ain’t in de bottom ob de sea, you is he’yar, and oh! I’se so glad to see yer.”

These poor creatures realize plainly enough that we are their friends, and they have never let slip an opportunity of showing us that their friendship is worth having.

—from “Our Black Friends Down South,” Harper’s Weekly, June 14, 1862

“Here,” she said, “in this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it. Love it hard.”

—Toni Morrison, Beloved (of Baby Suggs, holy)

Let Us Consider Sarah

Click for larger image

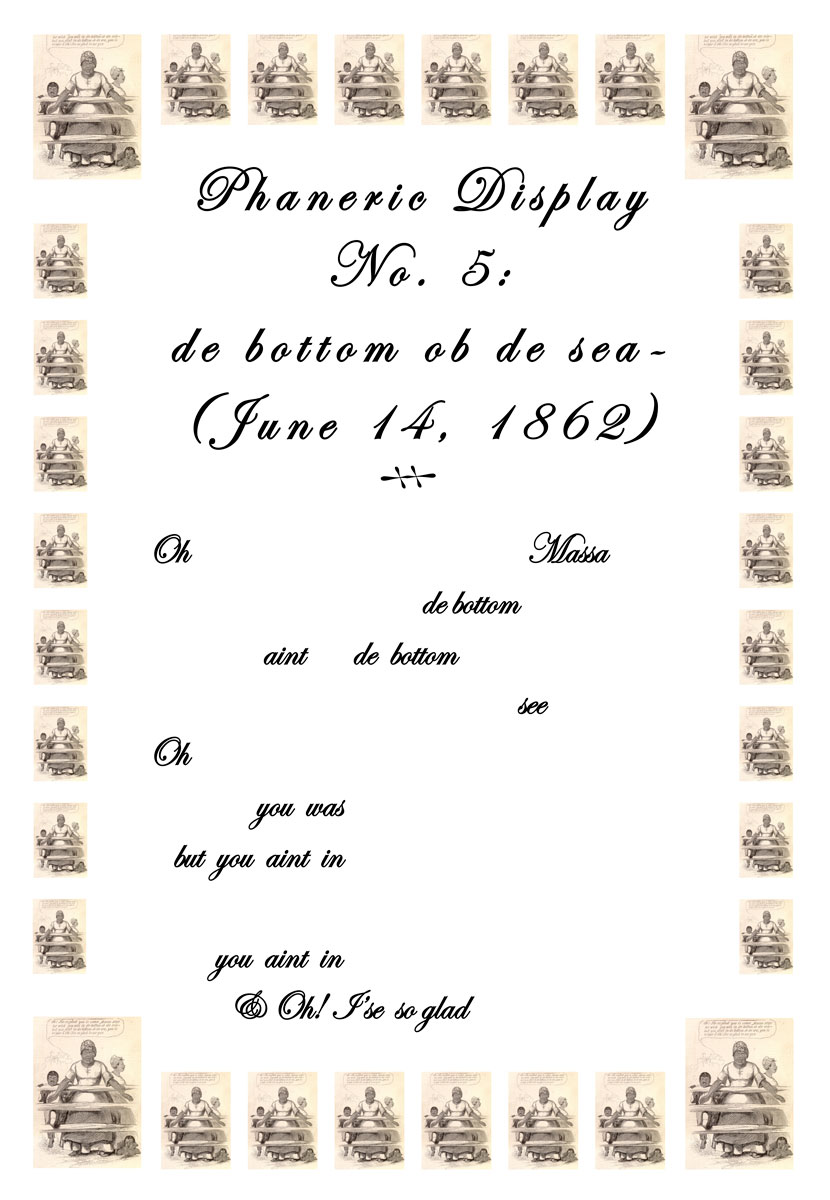

“Phaneric Display No. 5: De Bottom ob de Sea”3 designed by Duriel E. Harris using image from Harper’s Weekly (1862). Plate 1 of 2.

When I first come upon the image of the woman in the scene, with her neatly kerchiefed head, heavily lidded eyes, slight bosom, and welcoming arms outstretched over the fence, I do not know quite what to make of it. I am searching the Internet for images of a particular “negro mammy,” looking for a trading card I’d cited in an earlier poem some time before. “Lor’ bress yo’ honey!” the trading card caricature had declared. Ridiculed as an “uppity negress,” the woman had donned ill-fitting garish garb, and with a wide-brimmed sunbonnet and parasol she seemed to twirl, suspended in mid air. Her words were a series of awkward mispronunciations and exclamations common to whites’ spectacular late nineteenth-century buffoonery, their racist imaginations rendered in cork spit minstrelsy, mocking Black speech and manner, and through it Blacks’ suitability for freedom. But the Harper’s Weekly mammy is less of a spectacle. As an illustration for the column “Our Black Friends Down South,” she is fairly unremarkable, in her modest dress and apron. Though she is round in stature, there are no wide eyes, no clownish mouth, no dramatic scowl. The children with her are neat and pleasant looking, the woman behind her chatty and unconcerned. It is an almost neighborly image (a palatable motherly one?) but for (or due in part to?) the exaggerated dialect of the speech bubble. “Oh! I’se so glad you is come….”

The site on which I find the image nestled among other Civil War era Harper’s Weekly spreads labels it “Negro Mammy to Union Soldier.” Surely the original publishers’ intent can’t have been derisive. And the contemporary publishers? What of the impact, dear reader?

The image, as of now (2015) labeled alternately “Negro Mother” and “Negro Mammy” on the wistfully pastoral Civil War site, serves as the centerpiece of my proportional dialogue “Phaneric Display No. 5: De Bottom ob de Sea,” (Amnesiac: Poems) and anchors a series of musings on the figures therein: the frozen metaphor of the Negro mammy, her attendant accoutrements, and the specter of enslaved Black female bodies become one in their coded repetitions.

The musings are differential poetic events equally legitimate iterations, versionings manifest in different media, instantiations—embodied a cappella live performance(s), print text, recorded digital audio, live digital audio performance.

The figures are activated, re-envisioned, re-presented, in performance

captive. all but forgotten / obscured

Radically embodied

Click for larger image

“Phaneric Display No. 5: De Bottom ob de Sea” designed by Duriel E. Harris using image from Harper’s Weekly (1862). Plate 2 of 2.

With others in the series, the stylized text and image are re-envisioned and re-presented in my current on-going poetry-based theatrical project, the one-woman show Thingification.

When I first come upon the image, the woman, the scene, the seen, I want to work with it because I believe, I imagine, Sarah’s voice beneath the rubble. Her body, unfathomable.

Notes Toward Withness

But, Duriel, when is poetic activity = labor—alienated / alienating—a drag, a kind of death, a black body bag? And when is it something else—self possessed / life affirming, life giving—ala drag with swag (you better work!), a black body’s imagination extending realness into real objects in the world, to create and augment if not pleasure, in the least reward.

Or here, liberation. What would that look like now, in this specific instance, during this particular, situated, socio-historical moment? What does Duriel desire? With Thingification4? If there’s any exploration of the title here, it must be brief. We want at the meat—

What creative yield the vulnerability of flesh inspires. What its aliveness and injurability provoke us to imagine, to create. THIS IS INNOVATIVE NECESSITY!

As I begin this writing, as is often the case when I begin making in uncertainty, I ruminate upon selections from The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Attending to the push and pull, the demands of dis-ease and desire, I sidestep manifesto to turn toward the interior. What human need do I intend to meet? What longing, what hunger to satisfy?

To arrive at something useful. Surely joy. Worth the effort.

Amnesic, I have been a ghost in my own memory, absented to preserve the living body / self that has remained, vague / numb moving as fog and in fog

The veil / mantle / cloak / hood,

Breathing through the veil / gauze /

Moving through my life, as if in fog (the clinical diagnoses PTSD, GAD)

what besides my body and its intimates—the girl and boy suspended in the moments before drowning—haunts the theatre of my desire, fashioned of / in the new world that is my inheritance?

What creative yield the vulnerability of flesh inspires. What its aliveness and injurability provoke us to imagine, to create.

You Better Work, Bitch

To work, like a (drag) queen, is to “work” the body, to strut, to give an outstanding presentation, to put in the effort necessary to impress and stun

To strut: to dance or behave in a confident and expressive way,

to strut is to manifest empowered presence, display a recognition / understanding / embrace of one’s own value and the value of one’s expression(s), whatever one’s modes or manners—the self / body’s expression is always already valued / valuable, essential, a treasure—such that the expressive way, needs no external affirmation, confidence in self-expression… to be fierce and “own” it, to live it, to embody fierceness—

To impress: make someone / audience feel admiration and respect, to make a mark upon—in this case the psyche, to be unforgettable or better to resist amnesia, to make a mark upon the psyche such to resist ordinary processes of forgetting—to suggest, to teach, to encode differently on memory than just a passively witnessed something which would suggest that there would be some kind of emotional component? Research this—

To make the experience memorable:

Make as many neuronal / synaptic connections as possible, to strengthen memory

How much attention the people are paying (grab and hold their attention)

How novel and interesting the experience is, surprise, things people don’t expect

Have the experience be connected to something they’re already familiar with—building on existing connections

To work, is definitively a manifestation of lu-fuki—metaphorically this exertion would produce the sweat smell symbolic / indicative of the integrity of the bearer’s art. And yet it is more like sweat equity: contribution in the form of effort (as opposed to capital) [equity: the value of shares issued by a company, which translates to its market value]

Other ways of talking about work? You better

Work: do the activity requiring mental and / or physical and / or emotional effort to accomplish the purpose. Be engaged in the mental, physical, emotional effort required to accomplish the purpose, the task at hand. EFFORT: vigorous, determined attempt (but life into it, energy into it and also—determination, which suggests / means WILL)

Bitch:

A fierce woman, term of endearment amongst drag queens,

Latrice Royale’s acronym: Being In Total Control of Herself…

To say the emphasis is a being in total control of herself. Being—as an active state, Royale speaks here of presence, a fullness of presence, a kind of awareness, balance.

Here insert material about what slavery was / is like.

Changes that reshaped the entire world began on the auction block where enslaved migrants stood or in the frontier cotton fields where they toiled. Their individual drama was a struggle to survive. Their reward was to endure a brutal transition to new ways of labor that made them reinvent themselves every day. Enslaved people’s creativity enabled their survival, but, stolen from them in the form of ever-growing cotton productivity, their creativity also expanded the slaveholding South at an unprecedented rate. Enslaved African Americans built the modern United States, and indeed the entire modern world, in ways both obvious and hidden.

—Edward E. Baptist, “Introduction: The Heart,” The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism

Let Us Consider Sarah

How did Sarah endure bondage?

What were the details of her life?

Who / how did she become from one moment to the next?

What marked her embodiment, in motion, in rest?

Could there be such a thing as rest?

And the “nonevent of emancipation” manifest in the body as

Like other African Americans survived postwar poverty and other hardships of war and reconstruction by “pooling their meager resources....[w]hen all other tactics failed to meet subsistence needs, some among the poverty-stricken resorted to appropriating the food they needed from the backyard vegetable gardens of better-off residents.” (Hunter 24) —all of this depends on how you see it.

She was a domestic laborer—like she had been under the system of chattel slavery: a washerwoman, cook and maid of all work. Called Polly by her white employers. With the children… one in particular “her shadow” who fondly remembered her. (“From Recollections of My Early Life”)

What did she have to do to protect herself, try to give herself a life, make up for what she had lost?

There was some pleasure. What was it? How did her pleasure as a free woman relate to her pleasure under slavery?

Why is she a ghost? A haint?

At once recognizing her openness to them but at the same time holding on to racist ideologies that degrade, belittle, and demean. The both / and of Harper’s Weekly. Northerners, damned Yankees, were often both more accommodating of the possibility of the Negroes’ humanity than Southern, slaveholding whites and similarly and decidedly racist. Not quite a matter of degree. A different part of the same monster.

And by innovative necessity—because they will not let mammy go, must perpetuate her image and stance? Knowing what I know I must create Sarah, to complicate and interrogate the portrayal, the field of instance.

And what, where is the affective labor? Whose labor? Mine? Sarah’s?

Mine. I am an empath. I feel so much and have difficulty separating out others’ psychological suffering. Part of the difficulty of this writing, of considering, truly considering Sarah is the pain, disappointment, fear, disgust I experience when studying the Atlantic Slave Trade. I watch and weep, read and weep, listen weeping, find myself unraveling, heaving and then feel shame. But these are my ancestors, my kin, and this, my flesh. My suffering is both expected and suspect.

This Is Flesh

The making that happens through language in the play / onstage (i.e. Scene 1: You are a black thing—blackness and its attendant imagery are conjured; Scene 2: Audience is transported into the interior of a book (a volume of poems / a made thing), to a drawing (made) of a plantation scene created by an artist for Harper’s Weekly, the said drawing that appeared in the influential political magazine on June 14, 1862 featuring a caricature of a negro mammy, a doubly made thing—the figure of the negro mammy the beloved and faithful servant (cook, nanny, maid of all work), an American dream, a fulfillment of a wish made up (imagined) and made real (reified) in order to populate the US imaginary with a compelling fiction that serves as a public symbol of duty—the Lord loves a cheerful giver. & the caricature of the dream drawn in the cartoon, a wide dark figure, kerchiefed and aproned, with wide-open arms and happy darky enthusiasm marked most noticeably in her “typical” negro speech patterns. The speech bubble etched above her head “Oh, I’s so glad you is come!” welcoming the Union soldiers and the promise of freedom, deliverance in their care.

In live performance, the interior of the book, turned out such that the mammy—a determined fiction awakened and animated by the song in scene one, emerges, embodied. Mammy’s racialized exaggerations arousing Sarah, the ghost of a formerly enslaved woman, who forces her way into presence, speaking a truth long held silent during her life in captivity. This glimpse of Sarah’s truth followed by a song, a riff appearing in the book as a march (to fife, bugle and drum) typical of the music of the period with an atypical minstrel mockery solo.

This Is Flesh

FLESH

The prize is being able to feel, to sense

With regard to biology, flesh is the soft substance of the body of a living thing. In a human or other animal body, this consists of muscle and fat; for vertebrates, this especially includes muscle tissue (skeletal muscle), as opposed to bones and viscera. Animal flesh may be used as food, in which case it is commonly called meat. In plants, “flesh” is similarly used to refer to the soft tissue, particularly where this is the edible part of fruits and vegetables.

Considering the unshareability of (physical) pain, I have had certainty and I have had doubt. And the lack of awareness distilled as doubt has made it easier for me to cause injury to others and (more often the case) to move without regard for and inattentive to the pain of others.

The body in pain is omnipresent in the stage play Thingification as it is omnipresent in the fabric of American life / the US imaginary.

The distance between the body in pain and the body free to extend beyond itself into abstraction, the self with certainty and the self with doubt is vast; how much more so between other and self? As vast as the difference between slave and master? Between worker and capitalist? Between knowable object and knowing self? Between radically embodied flesh and disembodied voice?

Whatever pain achieves, it achieves in part through its unshareability, and it ensures this unshareability, through its resistance to language. (Scarry)

And further the anticipation of pain is pain.

Significantly, pain has a complex relationship with tissue damage. “Pain is a feeling that can be distinguished from other types of emotions and sensations by the way in which—accurately or not—it connects that feeling to a sense of tissue damage.” (Thernstrom) So, while tissue damage may or may not exist, the self that is in pain is experienced as sustaining physical damage, and is therefore inhabited by injury.

The slave or other so radically embodied as to be deeply woundable and fully responsible to the master. In the making when does the slave become an object? Or does the idea that the slave is an object come before the relationship between master and slave such that it is inherited by the master even as it is resisted by the enslaved person. The history of the idea moving alongside the history of the people.

*

[I have dissociative amnesia and for some time I fantasized about unmaking my amnesic self. Thinking that since the amnesiac, like any other thing, had at some point been conceived as an idea and then made manifest as an actual identity, I could hazard to deconstruct it / her and emerge otherly defined. Perhaps as if whole. Or somehow remade. Of course it wasn’t that easy. The profound memory loss could not / cannot be readily undone. The numerous episodic memories to which I have no access do not come when called, do not simply submit themselves to my will. But I did arrive at an alternative understanding of recovery, one that did not necessitate the restoration of what by definition has been lost but rather accepted the gaps and called upon invention as a fair substitute for absent memory. I returned my focus toward the process of making in earnest.]

*

Enslaved peoples daily invented—in order to survive.

The characters in the play emerge from innovative necessity—specifically Sarah, emerges against and alongside Mammy—a variation on form she has taken / adapted constructed for survival—a manifestation of the imagination, a mask—

Notes

1Taking up withness as primary mode was inspired by sustained interaction with poet Lisa Samuels, and initiated in writing / public speech for the panel “Withness: Thought-start in Creative-Critical Practice,” with Lisa Samuels, Marthe Reed, and Megan Kaminksi at the inaugural [Dis]Embodied Poetics Conference: Writing / Thinking / Being at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University in Boulder, CO, in October 2014. Other instances of withness informing this meditation include the panels “Poetic Labor: The Paradoxes of Making (It) Work,” with Catherine Wagner, Rodrigo Toscano, and Marie Buck and “Revisiting ‘Embracing the Verb of It: Black Poets Innovating,’” with Ruth Ellen Kocher, Douglas Kearney, and Lillian-Yvonne Bertram at the 2015 AWP Conference in Minneapolis, MN, April 2015, as well as conversations with Black Took Collective (myself, Dawn Lundy Martin, Ronaldo V. Wilson), Eunsong Kim, Tara Reeser, Evie Shockley, Erica Hunt, and Claudia Rankine.

Return to Reference.

2In this meditation I consider, alongside one another, several separate but related explorations of the US imaginary, specifically in relation to theory and praxis of my own contemporary arts practices. In these explorations I deliberately take up the mode of withness, engaging new writing and thought in the companionship of certain texts from my “ographe”—a subjective field of long-favored and often revisited fundamental anchoring works.

Return to Reference.

3Images originally published on line with audio at mipoesias.com (2007), collected in Amnesiac: Poems (2010).

Return to Reference.

4My title refers to Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism where he states colonization diminishes the humanity of both colonizer and colonized. Recognizing thing-ification as the annihilating objectifying force at the core of all oppressions, I make this analogy: like blues music is played to stomp blues feeling, Thingification is performed to stomp thing-ification.

Return to Reference.

Bibliography

Baptist, Edward E. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. New York: Basic Books, 2014.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Hunter, Tera W. To ’Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

JanMohamed, Abdul R. “The Economy of Manichean Allegory: The Function of Racial Difference in Colonialist Literature.” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 1 (1985): 59-87.

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley: Crossing Press, 1984.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. New York: Knopf, 1987.

Nielsen, Aldon L. Reading Race: White American Poets and the Racial Discourse in the Twentieth Century. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988.

Ronda, Margaret. “Work and Wait Unwearying: Dunbar’s Georgics.” PMLA 127, no. 4 (October 2012): 863-78.

Scarry, Elaine. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Thernstrom, Melanie. The Pain Chronicles: Cures, Myths, Mysteries, Prayers, Diaries, Brain Scans, Healing, and the Science of Suffering. New York: Picador, 2011.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. New York: Vintage, 1984.

“Negro Mother, Harper’s Weekly, June 14, 1862” Son of the South, accessed May 12, 2015.