The delirium of maritime things slowly takes hold of me

The wharf and its atmosphere physically penetrate me

—Álvaro de Campos

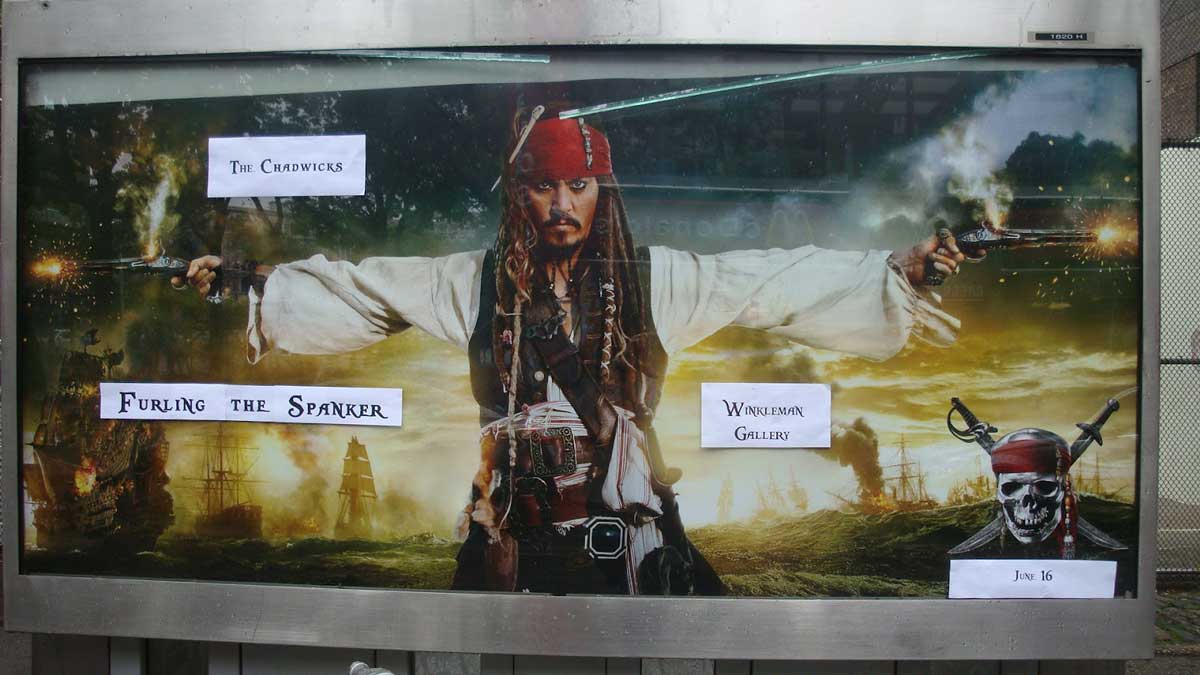

“Mumbai, Torrent, Mumbai,” I reminded a slumped form sinking further into a divan’s cushions. “It hasn’t been called Bombay for 16 years.” “The Indians may call it what they please, Mr. Shaw, so long as they don’t begin speaking of Mumbai Sapphire martinis or rename the city once again during your flight. There must be no missed connections: I want you and Mr. Blachly personally to accompany the Man o’Bar back to New York. Or do you insist on calling it New Amsterdam?” A flight to India; negotiations with museum officials who would certainly curse the Chadwicks’ role in their country’s history; packing of a ten-and-a-half-foot model; and then, if we were lucky, a two-month sea voyage on a container vessel around the Cape of Good Hope! This was several orders of magnitude more arduous than any errand we’d yet run for the family. And yet I heard Blachly agreeing without a pause. My neck spun nearly one hundred and eighty degrees to glare at him: it was all fine if, on his own time, he devoured Patrick O’Brian novels, lingered for unseemly periods in regional maritime museums, and scrawled misinformed nautical terminology into his notebook, calling it “sea poetry.” Committing me to this kind of undertaking was entirely different.

Back at the studio I hit Blachly with a gale-force berating. There was, to begin with, the abject financial nature of the Chadwicks’ proposition: under-budgeted travel expenses alone (perhaps half of what we’d actually have to spend), with no compensation for our time. Then there was the time itself: what on earth led Blachly to believe that I had two free months to give to an object I had never even seen, and about whose place in the family collections I had, frankly, serious doubts? Finally there were the manifold difficulties of the trip—negotiations, hardships, inevitable contingencies. Under normal circumstances—with a supportive client—I might even be okay with these. But things were different with the Chadwicks. Both of us knew that if we didn’t achieve precisely what they expected, the Chadwicks would hold us personally responsible—and perhaps dock our expenses. How would it feel to call them from Mumbai explaining that the Man o’Bar had actually been de-accessioned from the museum, broken into tiny shards to feed a funeral pyre, or that the curators wanted twenty three times more money than we’d established? How much support would we get then?

I was warming to the topic. And yet, it was as if the promise of the exotic nautical trip had rendered Blachly oblivious, thickening his oily skin into an impermeable membrane. There was something cretinous, to be sure, in the smile I couldn’t erase from his visage, but—I realized as I lobbed my string of objections and, later, insults—something contagious as well. And so in time I succumbed to the germ of a nautical voyage. Why not? I was on a year off from teaching. Perhaps I needed to stray beyond my comfort zone?

Mumbai had been frictionless. The curators were eager, in fact, to unload what they thought of as a lower-end relic of the colonial period. And so the trip had all seemed smooth enough—even glamorous—until one night in the middle of the Arabian Sea when the mosquito-like buzz of motorboats signaled the approach of the Somali pirates.

I could make them out maybe three hundred yards away, and closing quickly. Our crew on the Yaadon hadn’t seemed like the type for a gun battle. Which meant that, in the likely event of a ransom scenario, we’d be at the mercy of the Indian government, or, worse, the Chadwicks—who had neither the money nor the patience to be of much use. Blachly was snoring loudly. I gathered the essentials: water, beef jerky, rope, knife, flare—and rousted him. Though ashen and somewhat wide-eyed, he seemed surprisingly accepting of this turn of fate. Had he been abducted by pirates before? There was no time to inquire.

We had arranged for the Man o’Bar’s shipping crate to remain accessible during the voyage, placed at ground level at the bow, so that, during the long days at sea, we could open the front end of the container, pull the boat out on the weather deck, and begin the restoration process. This had cost some money in port, but was easily enough achieved. Now we made our way up the starboard side of the wall of stacked containers, invisible to the pirates, approaching from port, and wedged ourselves inside ours. The struggle didn’t last long. A few rocket propelled grenades, some rounds from a Russian-made machine gun—and the pirates were in charge. Several times they rounded the bow—sizing up the loot, securing the boat’s perimeter. But there didn’t seem to be a concerted search for us. Had the others lied about our existence? Had they imagined that we might rescue them? Two pirates sat guard on the bow—conversation filtering into our metal cell thirty yards away, where, baking, we tried our best to remain silent. But on the second night they made their way back to the navigation bridge—happy enough with its view, higher and covering most of the ship. Except those containers, like ours, that opened onto the weather deck. And so, about three o’clock in the morning, we quietly opened the doors, hauled the Man o’Bar out, and plunged over the Yaadon’s railings.

The hull rushed by us. Now we were to keep our heads under our vessel, which we hoped would either escape notice or appear merely as a piece of random flotsam. We heard no raised voices, no shots, saw no flares. From the corner of the Man o’Bar we could now see the cargo ship’s stern, receding into the distance. Apparently we were free—though also floating alone in the middle of the Arabian Sea.

Which brings us to our precarious life raft, the Man o’Bar, whose proper introduction has thus far been rendered impossible by the rush of events. Clinging to it day and night in the open ocean, however, brought us more than enough time to appreciate this singular curio. Especially since I had stopped speaking to Blachly, except to issue brief commands. My thoughts in his direction, upon our plunge into the water, had been reduced to a single question: could I bring myself to eat him? I saw no ethical objections—the problem was entirely aesthetic, or, gastronomic. But so far the beef jerky was holding out, and thus we floated in relative peace.

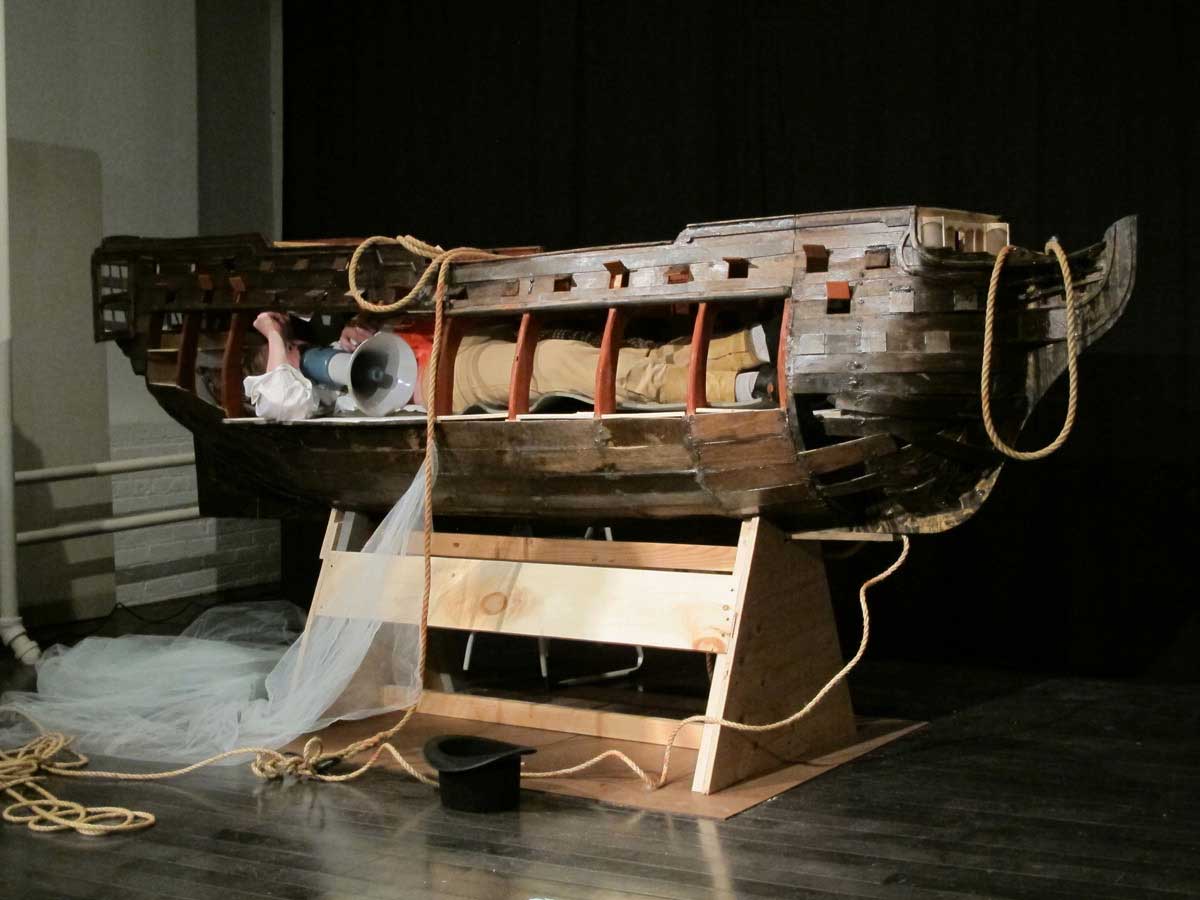

Life raft—that was a new resume line for the Man o’Bar, which already had a surprisingly long one: sea cinema, study center, casket-like proscenium theater, theme pub—the Nelson Man o’Bar has been tugged from the beginning between the scholarly and the spectacular, the precise and the preposterous. The mysterious object was constructed initially as a scale model for Lord Nelson’s customized HMS Victory, the boat the admiral commanded in his decisive sea campaign against Napoleon, and on which he was killed by a French sharpshooter during the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. As the English nation mourned the loss of this newly deified sea savior, and churned out all manner of memorials to his life and labors, the Chadwicks quietly purchased the model itself. It is described in the family papers as a “machine for private grief.” Most writers have glossed this ambiguous phrase as a shrine. But our dive into this region of the archive, before the fateful Mumbai jaunt, suggested rather different uses: apparently the Chadwicks found the passive contemplation of the boat as funeral monument too remote and discovered that, by removing sections of the exterior planking, it was possible, through some exertion, to wedge a human body fully inside the hull. Chadwick Dalton was the first to attempt this nautical model spelunking. Inside, Dalton would re-enact the known portions of Nelson’s famous death speech—which had in life lasted three hours, much of the duration of the Battle of Trafalgar. Perhaps impatient with these monologues, and certainly less interested in scholarly reconstructions (or, as he called them, “historical reinaccuracies”), Torrent Chadwick then began, on Dalton’s absences from the manor, to use the model as a kind of nautical pub—and it was he who introduced the term Man o’Bar. At once prop for historical mourning, and nautically-themed bar, the model navigated this cross-current of conflicting uses at Chadwick Manor until sometime in the 1940s.

Then, as the family’s debts mounted, the Man o’Bar was sold, first to the Maritime Museum in Greenwich, which, unannounced to the family, sent it off (possibly for authentication) to a maritime specialist at the Victoria and Albert Museum—in Bombay. There it was displayed for some years until that institution, too, decided to dock the vessel in mothballs.

By the third day I could barely see. The glare had worked its way back inside my head. At points Blachly appeared to me as a slightly undercooked porpoise on a spit—though this may have been an optical illusion caused by him clinging to one of the masts that had, by now, fractured off the boat. As yet he wasn’t even a vaguely tempting meal. Our first hours in the water had been the most difficult. When we tried to install the sails we discovered that they’d been largely devoured by insects. It had been Blachly who’d recommended keeping them furled until we reached the studio. Though I still held him responsible for our predicament, the very hardship seemed, after three days, to bring us together somewhat. At regular intervals he doggy paddled a few strokes to retrieve rigging fragments or parts of the model that were by now regularly breaking off. These he then wedged as best he could into openings in the Man o’Bar. Since neither of us had much strength left, I interpreted this shepherding of the model as a gesture of reconciliation. More, the boat listed strongly to port in the open water. And it was only with one of us kicking from behind and holding the Man o’Bar straight that the other could find respite on the deck. But since my ankle was still swollen from a break six months earlier, I pleaded for a smaller share of the paddling. Blachly accepted. And so it was that I was “on deck” when, mid-afternoon on the fourth day, a vessel came into view. I waited a few seconds to make sure the appearance wasn’t another optical trick—got Blachly’s confirmation—and then fired the flare.

“Non ho mai visto una cosa così! Giys thes ahhhhh … boat … esn’t deesined for d’open seas.”

It was an Italian freezer trawler that, tempted by the richer waters of the Arabian Sea, had made its way through the Suez Canal to fish from the Gulf of Aden up to the Gulf of Oman. Luckily it was now on its return voyage. Amused to no end, the fishermen hoisted the Man o’Bar onto the deck and got down to studying it—and us. We were apparently the most exciting catch they’d made on the entire trip. Eruptions of laughter and idiomatic phrases in a Neapolitan accent I couldn’t understand punctuated their examination. I tried to explain the circumstances of our winding up floating on the boat. But nothing I could say in my poor Italian could disabuse them of the idea that we had set out in this vessel. Still, their ridicule was a small price to pay for our deliverance.

Safely below deck with a full stomach and a glass of grappa, Blachly confessed a story that shed new light on what had seemed to me the extraordinary endurance he had demonstrated during our four days at sea. It concerned an event that, until then, he had been too embarrassed to narrate to me. But now our new ordeals apparently put this previous event into perspective. Our conversations about going to Mumbai had occurred, in fact, several months after we had first learned of the Chadwicks’ interest in putting together a blockbuster nautical retrospective. At the first discussion of the show, Blachly’s response, unknown to me, had been rather different from his later blithe acceptance. “I was terrified,” he confessed. I paused to clarify: “Wait, a two-month trip aboard a cargo vessel was fine, but the prospect of co-curating a nautical exhibition sent you into a crisis?” “All I knew of ships was from Patrick O’Brian, and actually I didn’t really understand a lot of the vocabulary in the novels.” Lacking a solid nautical education, Blachly had worried that his new task would expose his ignorance—or, worse, cause him to make irremediable errors during restoration. And so Blachly, then nearly 50, had resolved to confront this problem by going to sea, or at least going near to sea: the next week he had volunteered for an internship on a schooner called the Pioneer which, owned by South Street Seaport, made tourist voyages out into New York Harbor, and occasionally beyond. I had known all about his internship; it was Blachly’s style to take on, with each project for the family, a version of the Chadwicks’ life within his narrow means. This helped him comprehend his work. But here the discrepancy had seemed simply abject. Still, I had overcome this feeling and even accompanied him out on the schooner one day, documenting the nautical knots and rope coils in a manner that had made some of the more butch lads aboard slightly uncomfortable. I had even helped Blachly learn the arcane vocabulary required on board the ship, a project that had given rise to a pamphlet called Practicing Nautical Sentences.

What I didn’t know, however, and what Blachly now began to narrate, was an event that had occurred some weeks before my first and only voyage. He stumbled often in the narrative, described key elements in vague or imprecise ways, and generally lacked the zing I would like this pamphlet to radiate. So I’ll avoid cumbersome quotation marks and just present my own version of his story. The conflict began with the hoisting of a sail, an activity requiring the full participation of at least two deck hands. On this day Blachly’s hoisting mate was a woman named Elizabeth, who combined a salty knowledge of things nautical with an elegant and well-exercised torso. Or so it struck Blachly, who betrayed a fascination with the lone female mate upon their first co-hoisting operations. On this fateful day, however, when the ship was making a celebratory cruise part way down the New Jersey coast, Blachly had taken advantage of her arms’ occupation with the rope to drop his portion of the burden and lift her shirt enough to catch a full view of the anchor tattoo on her stomach. A roundhouse kick to the temple had halted Blachly’s inquiries. When he rose, sheepish and swollen, he had been ordered to furl the spanker, a dangerous operation he had accomplished only once before, with significant aid. This time, however, Elizabeth turned her back, joining the rest of the crew at the bow. And so it was, a few minutes later—after he had climbed into position—that Blachly’s accidental plunge into the sea went unnoticed. When he came up to the surface an intense wave of embarrassment sealed his mouth. Then, just as he had gathered himself to scream, he was swamped by a real wave. By his third rise, the ship was out of range. He was about two miles from shore. A doable swim, if he could find some jetsam on which to rest. Before long he had located a plastic bait cooler—fetid, sticky—to which he clung periodically. In about three hours he had washed up on Sandy Hook. After this unexplained departure, the crew aboard the Pioneer insisted on calling him Lord Jim-bo.

The trawler made its way around the boot of Italy and docked in Naples. There we flipped a euro to see who would call the Chadwicks. Blachly looked at the coin once it had landed, and then flipped it over once more into his other hand, as if he had intended to do that from the beginning. I protested.

But since we hadn’t specified just a flip, or a flip and a slap to the other hand, it was I who steadied myself for the barrage to come: the container was gone, the boat was severely damaged, and we were late. “You’re in Naples you say, well that may be a stroke of luck.” Had Dalton located his lost laudanum supplies? Where was the explosion? “Well, do your best with restoration in the field—we’ll simply have to finish it in the studio. And while you’re waiting for a new shipping container, gather all the materials you can on the Chadwicks and Winkelmann for the 2017 tri-centennial exhibition, and on Admiral Nelson’s stay in Naples. I’m sure the family name still opens the gate at Palazzo Sessa.” I didn’t question.

That the Chadwicks would have felt a deep connection to Admiral Nelson is not surprising. Nelson was noted for his ability to inspire the best in his men: the Nelson Touch, as it was called, which became even more focused after he lost an arm at the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife in 1797. Indeed, the admiral’s grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics produced a number of decisive victories, especially the Battle of the Nile (1798), the Battle of Copenhagen (1801), and, of course, the Battle of Trafalgar. When standard military strategy dictated that commanders brought their line of frigates parallel the enemy and then fired at close range, Nelson perfected a method of slicing through the enemy line, isolating one section of the opposing fleet and destroying it while the other hostile ships tacked to reposition themselves.

Nelson’s ties to the Chadwicks emerged through mutual connections, in particular the Hamiltons—Lord William, British Envoy in Naples, and Emma, Lady Hamilton, with whom Nelson carried on an open affair. It was also through the Hamiltons that the Chadwicks first made the acquaintance of their current gallerist’s predecessor, art critic Johann Joachim Winckelmann, whose life was cut short by a hustler and petty thief in Trieste in 1768. Thus Nelson, who was born in 1758, was 10 years old when Winckelmann died: old enough, that is, to have translated the Odyssey, published three or four books of poems, and had several romantic liaisons at Eton, if one was a good English literary prodigy. But Nelson was bound for the sea, not the study. His rise was to take place amid the rough shouts of deck hands, not the lisping of antiquarians. And so he did not meet the famous critic of Greek sculpture.

And yet Nelson got on surprisingly well with the learned. His close friend Lord Hamilton, or the Cavaliere—as he was known—was, judging by volume of patronage, among the most distinguished Neapolitan antiquarians. He collected more than 1000 Greek vases; 600 bronzes, 375 pieces of ancient glassware; 175 terracottas; 6000 coins, along with cameos, intaglios, gems, statuary, erotic curiosa, and paintings—some 350 canvases. The publication of Hamilton’s collection of classical antiquities—Antiquités étrusques, grecques et romaines (4 vols., 1767–76, text by Pierre François Hugues)—was a massive work for which he paid more than 6000 pounds.

The impact of these volumes throughout Europe was profound, and played a major role in the development of neo-classical aesthetics, as did Lady Hamilton’s famous “attitudes,” in which she posed for distinguished guests (Winkelmann, Goethe, Beckford, the Chadwicks, Nelson) as various classical figures, draped in antique costume. Hamilton tutored her in these performances, and even designed a black-velvet-lined niche for her to stand in, encasing her performances in a backdrop similar to those on his vases and cameos. It may have been this willful confusion between objects and persons that led Hamilton’s close friend Horace Walpole to remark that the Cavaliere had “actually married his gallery of statues;” and it was probably also what led Goethe to describe Emma as an “object” (Gegenstand) to which Hamilton’s “whole soul was devoted.”

Apparently, though, this soul-devotion left room for the living sculpture to mingle freely with other bodies—like Nelson’s. The Chadwicks seemed to have hoped for similar contact with this intermediate matter—encouraged not merely by the stories of Emma, but by those—from William Beckford—about Hamilton’s first wife, Catherine. Like Beckford, the Chadwicks cloaked their advances under pleas for guidance from a sympathetic woman who fully understood their maladies. All of which may explain their protracted visit at Palazzo Sessa, which tested even Hamilton’s patience.

Together with charges that a Chadwick lifted erotic curiosa from the collection, and tried to broker an antiquities sale with a known tomb looter—such were our discoveries in the Palazzo Sessa archive. The palazzo sits on Vico Santa Maria Cappella and overlooks the Bay of Naples. We, however, were in the basement, previous site of the Cavaliere’s collection storage—a location only a few visitors in the eighteenth century were invited to see, most being offered only a tour of the study. There was of course much more to learn—but given the view of the family in the documents so far, we decided not to wait another week for the two hours—Wednesday from 1 to 3pm—the archive was open to the public. More discoveries like these would no doubt end the Chadwicks’ inexplicably good humor.

And so, when the Finish container vessel on which we had booked passage was ready to depart from the Port of Naples several days later, we did not hesitate to board. There was no coast of Somalia between Naples and New York. Only beloved Palma, Gibraltar, and Cape Trafalgar itself, the little-known site of the battle that gave its name to the square at the symbolic center of imperial England. As we floated past these locations, our attention turned once again to Nelson. The terrors of our ordeal in the Arabian Sea now safely behind us, we began to bask in the admiral’s biography, trading famous Nelson quips one for one on the forecastle.

Blachly:You know, Foley, I have only one eye—I have a right to be blind sometimes.

Shaw:I have fought contrary to orders, and I shall perhaps be hanged: never mind, let them.

Blachly:Take, sink, burn, and destroy them.

Shaw:Our weather-beaten ships will make their sides like plumb-pudding.

Blachly:Our plumb-pudding will make their insides like weather-beaten ships.

Shaw:You know, Blachly, I have only one good ankle—I have a right to be towed sometimes.

Blachly:There is no way of dealing with a Frenchman but to knock him down.

Shaw:All Frenchmen are alike—a country of fiddlers and poets, whores and scoundrels

Blachly:I believe that’s “At least country poets aren’t like French whores.”

Shaw:Although a military tribunal may think me criminal, the world will approve my conduct.

Blachly:Let me alone, I have yet my legs left, and one Emma.

Shaw:They have done for me at last, Hardy … my backbone is shot through… my sufferings are great, but will soon be over.

Blachly:Brave Emma! Good Emma! If there were more Emmas, there would be more Nelsons

Shaw:I never saw fear, what is it?

Blachly:Brave Emma—it’s a Frenchman’s enema!

Shaw:I am ready to quit this world of animus, and envy none, but those of the estate six feet by two.

Blachly:Oh! How I hate to be stared at!

Shaw:If it is a sin to covet glory, I am the most offending soul alive.

Our banter had been very much like historic sea warfare itself: Blachly, not three feet from me, firing a Nelson quip across my bow; and I, then, answering back, letting loose the best word-volley I could remember. But, temporarily out of ammunition, we had come to a stalemate. “Kiss me, Hardy,” I offered as a truce. But Blachly was not so easily pacified: “Kismet, Hardy,” he corrected, and explained how, considering “Kiss me, Hardy” a little light in the docksiders, the most pressed polo-shirted of naval historians had argued that in fact Nelson was suggesting that his death was a matter of “kismet” or fate. Smooch me, undersecretary could simply not have been the last words of the fiercest naval commander in the history of western civilization! Or perhaps, I countered, Nelson was actually disputing the fatefulness of the French sharpshooter’s hit: “Kismet, hardly!” His speech was rather slurred by that point in the battle. We seemed to be gearing up for more broadsides of banter.

But at just that moment Blachly did something genuinely surprising: he abandoned his defensive position alongside me and, with a brief narrative, shot through my line of prepared quips! Blachly’s story, which again I prefer to narrate myself, concerned the resolution of his time aboard the Pioneer. On the subsequent extended jaunt up the New Jersey coast the weather had been rather rougher. Squalls had started in the harbor and, by the time the schooner was under the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, there was talk of returning to port. But the captain had pressed on. It was at this point that Blachly asked to be lashed to the mast. This was not a defense against the siren songs of the mysterious Perth Amboy! Blachly was not now tempted by that greasy vortex of American art history. No, to the contrary: he wanted greater immersion in the present storm. He pined to become an embodied eye, engulfed entirely in the violent elements. Not winding up floating on a cooler back to Sandy Hook this time would also be a plus. The deck hands had, at first, protested at this novel request from a mere intern. But it was Elizabeth who had overcome their objections, cinching the ropes to the point of blisters as Blachly was hoisted into position, grimacing (with anticipated pleasure?) until the others had gone below deck. Now the drama began. Blachly was pitched violently over the troughs of waves, up high into the air, and then down close to the sea’s surface again as the boat swung erratically through the enormous swells. He nearly passed out with the first few lunges, wetted himself excessively, then emitted wide arcs of vomit over the seascape and deck. But once he had emptied himself and become acquainted with the ship’s range of motions, his terror began to abate. Gradually he was impressed by a vision of the murky, swirling environments with which he would overlay his copies of drawings from the Chadwick nautical archives.

But something else happened on that mast as well. After ten minutes the bobstays parted and the spanker, one of the few sails small enough to remain usable in this weather, ripped from earring to clew. By this point Blachly’s harness was slightly less snug. He discovered that he could wiggle an arm entirely free. From there it was only a matter of moments until he was, to his thrill and horror, merely holding onto the mast that swung with such violent motions. But now these lurches were more predictable. His steps up the mast were quick and assured. He located the spanker, furled and unfastened its two separate sections—and reattached a new sail in their place. His actions were so fast that the crew, concerned with the immediate dilemmas of navigation, had not even glanced up until the task was accomplished. Even Elizabeth was less icy when he rejoined the sailors below.

Several days later, as we were finally coming in view of New York harbor, I felt somewhat empty on seeing the patch of coastline Blachly had described in his story. Yes, I had had more nautical experience. Yes, this had better prepared for the Chadwicks’ current retrospective. And yes, most of all, I had had downright unbelievable adventures on this journey to retrieve the Man o’Bar. But despite all this I wondered if I might not have missed something in not accompanying Blachly on his expedition up the New Jersey coast—and particularly in not having myself lashed to the mast of the Pioneer in a storm.

What was it about my own experiences that made them less attractive than the ones I knew Blachly was exaggerating? What was it about my immediate, tangible domain of scholarly seafaring that made it seem less powerful—less total, less immersive—than his imperfectly and partially recounted stories?

No, Blachly was clearly overstating his accomplishments. Had I been there, I’d have been able to frame the events in a more accurate way. They would have seemed, as they did now that I really thought about them, but a prelude to our real drama of recovering the Nelson Man o’Bar. Perhaps the Chadwicks were rubbing off on him—with their sense that whatever they had done was the most important thing in the world, no matter how far fetched, peripheral to the culture at large, and amplified in grandeur. If we often found ourselves agreeing, this was only because with them—at least—we were offered the adventure of tacking in pursuit of their claims in that vast ocean of evidence—the Chadwick archive—to which we were now returning.