—Joshua Ware

Poetry

This is not scientific, but every kid

who watches minor league baseball in a river town

becomes a poet. Where, at every game,

clouds of mayflies mob the field,

blooming around the false moons

of stadium lamps. They frost clothing,

our hair, and even eyelids with their bodies,

and inevitably someone’s dad says

how short their lives were,

24 hours and sometimes less. If you’re a kid

when you hear that, the concept of a day

relatively new to you, you try staring

at one of their intricate wings up close,

its membranes the work of a seamstress

in your fingers. You later recognize this

as Poetry, like what Carl Sagan said

about our human bodies being made

of star matter. But it’s too easy, making

a poem out of a mayfly or Carl Sagan.

And hard to resist seeing jellyfish

in a photo of a supernova when I want to see

a gaseous cloud moving since, literally,

the start of time. Bees are too much

to take, with their irresistible

honey, and queen, and swarms,

admit it. Aristotle wrote about

the ephemeron, a species of mayfly,

and scientists love to point out how wrong

he was, but then, he wrote the Poetics

about tragedy, and he called opsis,

or spectacle, the least artistic part of it.

—Erin Hoover

I’m Swallowtail-Young

Voices of the past cried out, Don’t forget me.

Don’t forget me nodding in the wallop,

Don’t forget me wrongfully seized along the callose wall,

Don’t forget me knotting, rolling,

in the warty pipevine,

Like colpi: a knock, a shock, a shot

of pollen! A blast of autotrophic

Aristocracy

Rolling in the pollen-coat of discipline,

writhing in the guzzle-cup,

pounding corpse-like nectar castagnettes

carcinogens

surround, inflata, tongues of camera,

camera sounds, aperture, aperture

Aristolachia

trumpet-punctum

And what pipevines out from trumpet-bod?

Aristolochic acid!

It spits the pollen in status-quo fashion same way

television spits 256 shades of red, 256 shades of blue,

256 shades of green—16, 777, 216—the number

always trying to influence my diet, always

trying to negate class, trip up my pillar-crawl

But I know my class: insecta.

I accept it, I do. And I’m not to be tampered with,

not meant to help grow you all

Richly glanded, spreading like fungmoss

“healing,” “cancerous,” “worm-killer”—top speed ejaculate!

Your powder, your power, your top speed ejaculate!

Thankfully I’m weed-killer of the kingdom Animalia!

the scent, a thread I know far too well

Call me Swallowtail!

I’m larva-young,

I’m Swallowtail-young,

I’m forked with

adornments, I’m stout with

compartments, sepulchral inscriptions

I’m a far fall from where I’ll one day be!

With farfalle wings, through canopy,

through sacellum: I will be praised

Call me Swallowtail! At the unction,

But at the moment I trapeze shapely

along the peristome, all lipid-lidded

I bring down the pretty weeds, I bring down

the haustorium, I nail a spike into

prey-capture effectiveness stats,

Because I dine (unlike the others),

on Aristolachia, I’m quite chlorophylled,

with all the rich, I do eat the rich,

I do eat them, glands and all.

—Paul Cunningham

In insects which are beheaded, however readily they respond to stimulation of the nerves, they are almost completely wanting in will power. Yet insects which have been decapitated can still walk and fly. Hymenoptera will live one or two days after decapitation, beetles from one to three days, and moths (Agrotis) will show signs of life five days after the loss of their head.

That the loss of will power is gradual was proved by decapitating Polistes pallipes. A day after the operation she was standing on her legs and opening and closing her wings ; 41 hours after the operation she was still alive, moving her legs, and thrusting out her sting when irritated. Ichneumon otiosus, after the removal of its head, remained very lively, and cleaned its wings and legs, the power of coordination in its wings and legs remaining. A horse-fly, a day after decapitation, was lively and flew about in a natural manner.

—Alpheus Spring Packard, from A Text-Book of Entomology, Including the Anatomy, Physiology, Embryology and Metamorphoses of Insects, for Use in Agricultural and Technical Schools and Colleges as Well as by the Working Entomologist

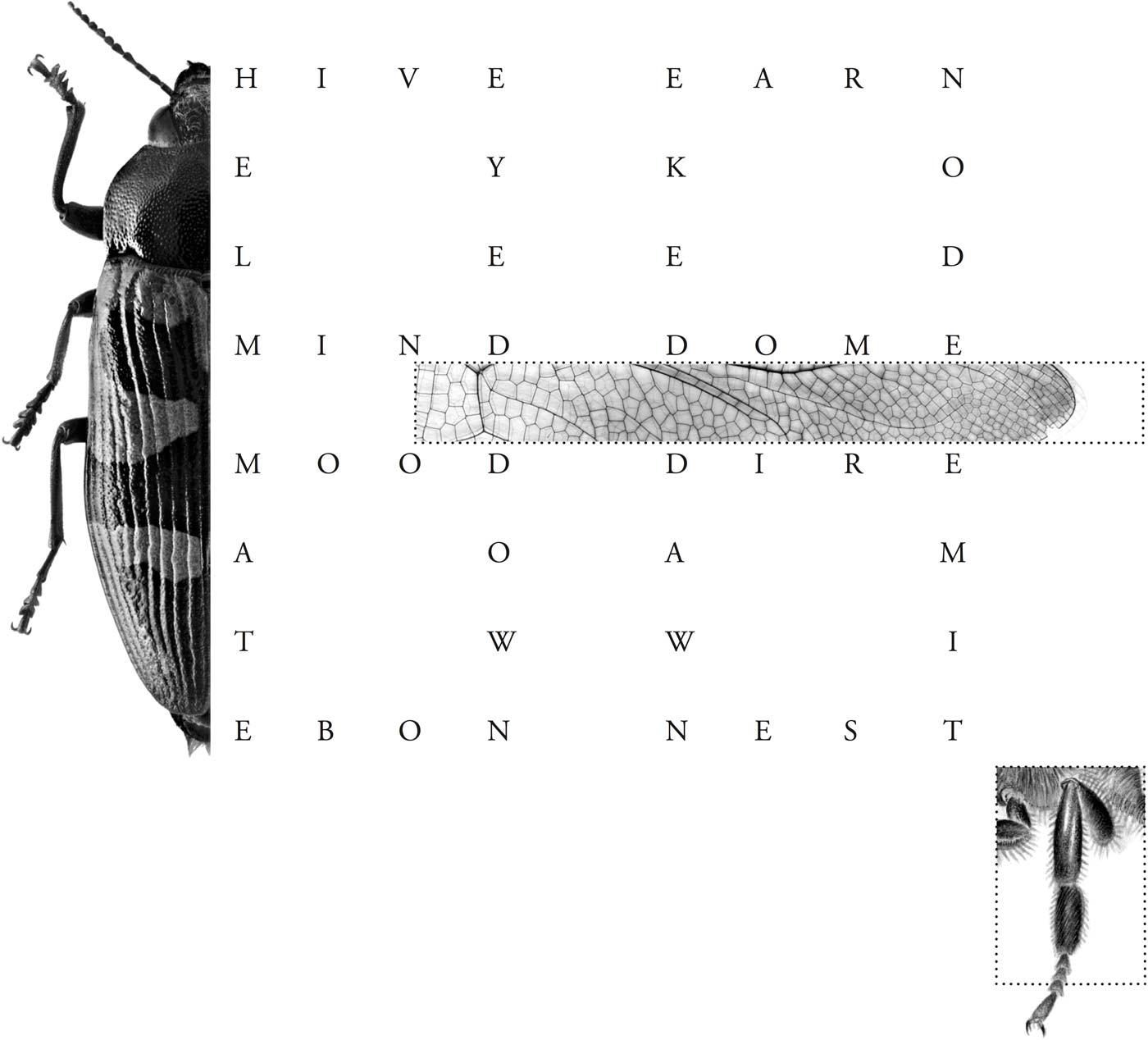

Gluing Parts of different Aphids together.

The auxiliary verb

Pliable in its form

To become buffalo

Which rides me like I ride,

An adjective.

No mandible holding the jaw

In place, the skeletal structure

Askew.

Outer lobe or galea maxilla, not an ear

Or an eye. As in divided (thread-like) or nearly so.

Begin with the mammoth

Gently erase his hindquarters into zigzag

Transverse shapes.As in tarsal, cylindrical, common.

Gently replace an antenna with a marsupial.

Sew along the dotted line and cut

Out femora.

Measure wingspan

Only a few strokes redrawn, then ask

Again, where I am found ovate, convex, interrupted

By a bright red sutural stripe or something

Left over from birth.

Antennae and legs pale.

Begin with one or two pairs

Of forceps.

Then crawl bull-like

Across an outer-edge.As in prothorax long and slim,

First segment short.

Remove the insides,

Examine several tiny wingless species

Diagonal stripes on femora

And now your hands are found folded

On leaves, bulbs and pigeons.

Otherwise unwoven. As in smell like a species of bird

Cared for in the early days of entomology.

*If antennae are filiform the first ventral segment should always be examined.

Look closely to distinguish it,

They are usually Staphylnids.

—Andrea Rexilius

First Published in Volt, 2005.

I was once a humdinger

An ensorcelled luscious butcher

I netted a howler

& the days collapsed

like ha ha

During the riots

I bit in2 my own

insect nerve

Now I’m ajerk

in neo-animal furs

Newly brain-free

Open the sunless socket

Make an army

of my voided joy

~

Boom Boom

is almost dead

Hi bunny

I’m trolling 4 murder

Riding swags of glory

I sew on my swine head

I snoop around

this strict machine

4 some plug ugly joy

Don’t tell the president

I’ll let you lick my insect

~

The neo-animal

gushes in the hole

Perforated lungsparkle

meatjoy

I’m crouching atop

the termite century

Pink + weaponized

my arousal goes feral

This is gestural pudding

The tumor crown

Don’t think around the muscle

I’ll loosen it all up 4 u

w obscene balloons

+ high kicks

My neo-animal army

is foxy like that

—Lara Glenum

In Every Fried Pie

Insect poetics might be said to be about scale, considering that beetles alone represent a fifth of all living organisms and a fourth of all animals. Or span—as midges, mayflies, and mosquitos colonized air, land, and sea, making their wingless ways from the Sahara to Antarctica. Or time—since progenitors kin to fishmoths circling our bathtub drains traversed dinosaur dung, their world-wise ancestors having emerged 420 million years ago.

As if the top of my head were physically removed, I ponder their individualism.

The lens that could encompass such magnitude justified monotheism. Then cracked. Linnaeus died an unhappy man, his life’s work of taking God’s species two by two names into the catalog endless as Sisyphus’.

And what of the translation, which may as well be intergalactic, considering the distance from sonogram to the Latin alphabet. Do the cadences treehoppers thrum across neem branches not mean but be, their concert forever irreducible? And doesn’t such a radically different system of communication alter beauty’s definition.

Rather than an aesthetic in opposition to usefulness, the orb weaver’s form follows more than function. Biology’s brass knuckles glitter with a comely luster. As if this planet’s garment is featherstitched not against reason but to lift it, hemmed in celebration of all that checkers infinity’s niches. I might even call it Appalachian, bound as it keeps being to squeezing something out of nothing, and that something sumptuous as a butter-full cauldron of mason bee-pollinated apples.

—Amy Wright

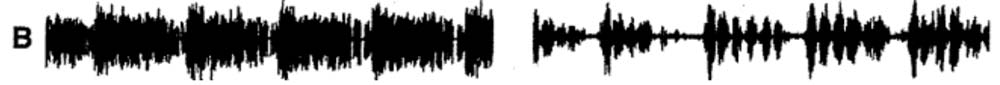

[ insect sound ] by [ insect light ]

That his ear still might echo,1

strophic reversals and profound regressions that seem2

serve as an assembly call. While the hunt is on, short, rapid3

“The Curved Lens of Forgetting”4

the eye. Through a tiny instrument one sixth of an inch across,5

mediates recycling of Cl ions back to the lumen in order to resupply parallel6

other that kind of truth—truth of structure, relation of parts,7

Thus female Pieris at first show a preference for blue, purple, and yellow, the colours of8

dominance hierarchies vary according to conditions, as9

They buzzed straight up from the collecting sites, and it apparently re-11

1090 Morse, Albert P. 1897. Notes on New England Acrididae, III. Oedipo-12

strophic reversals and profound regressions that seem13

do you know she’s there? // Balanced lightly on a leaf,14

jornais e a cor da letra kou / Boulevard Raspail Stein Sorgues15

bador Peire Vidal or Emily Dickinson. There was a luminosity about16

light experiments of, 166-174 Nippur, ruins of, 817

equipotential, where they ceased to record18

All systems of classification in practice are hierarchical; animals are placed19

who sat his village blacksmith ‘under a spreading chestnut tree’ knew what he20

ing) and the inaccessible dream of the human sciences (the utopian21

‘I must leave this hotel,’ was her only thought, and she slept22

—Edric Mesmer

Notes

1Wright, James Arlington. The Branch Will Not Break: Poems. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1963: 14.

Return to Reference.

2Ronnberg, Ami., Kathleen Martin, and Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism. The Book of Symbols. Köln ; London: Taschen, 2010: 110.

Return to Reference.

3Selsam, Millicent E. (Millicent Ellis), and Kathleen Elgin. The Language of Animals. New York: Morrow, 1962.

Return to Reference.

4Sears, Peter., and Michael Malan. Millennial Spring: Eight New Oregon Poets. Corvallis, OR: Cloudbank Books, 1999: 99.

Return to Reference.

5Highet, Gilbert. The Powers of Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1960.

Return to Reference.

6Gerencser, George A., and Gregory Allen 1943- Ahearn. Electrogenic Cl- Transporters in Biological Membranes. Berlin ; New York: Springer-Verlag, 1994.

Return to Reference.

7Burroughs, John. John Burroughs’ America: Selections From the Writings of the Hudson River Naturalist. New York: Devin-Adair, 1951: 51.

Return to Reference.

8Chapman, R. F. (Reginald Frederick). The Insects: Structure and Function. New York: American Elsevier Pub. Co., 1969: 569.

Return to Reference.

9Gordon, Deborah (Deborah M.). Ant Encounters: Interaction Networks and Colony Behavior. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2010: 110.

Return to Reference.

10Gerhardt, H. Carl., and Franz Huber. Acoustic Communication in Insects and Anurans: Common Problems and Diverse Solutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002: 102.

Return to Reference.

11Hutchins, Ross E. Insects. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966: 266.

Return to Reference.

12Frings, Mable., and Hubert Frings. Sound Production and Sound Reception By Insects: A Bibliography. [University Park]: Pennsylvannia State University Press, 1960: 61.

Return to Reference.

13Ronnberg, Ami., Kathleen Martin, and Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism. The Book of Symbols. Köln ; London: Taschen, 2010: 110.

Return to Reference.

14Frost, Helen, and Rick Lieder. Step Gently Out. Somerville, Mass.: Candlewick Press, 2012.

Return to Reference.

15Bonvicino, Régis R., Régis R. Ossos de Borboleta. Selections Bonvicino, and Michael Palmer. Sky-eclipse: Selected Poems. København ; Los Angeles: Green Interger, 2000.

Return to Reference.

16McClure, Michael. Lighting the Corners On Nature, Art, and the Visionary: Essays and Interviews. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, College of Arts and Sciences, 1993: 93.

Return to Reference.

17Mlodinow, Leonard. Euclid’s Window: The Story of Geometry From Parallel Lines to Hyperspace. New York: Free Press, 2001: 301.

Return to Reference.

18McGill, Thomas E.. Readings in Animal Behavior. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1965: 65.

Return to Reference.

19Ridley, Mark. Evolution. Oxford [England] ; New York: Oxford University Press, 1997: 197.

Return to Reference.

20Thomas, Peter, and John R Packham. Ecology of Woodlands and Forests: Description, Dynamics and Diversity. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007: 407.

Return to Reference.

21Raffles, Hugh. Insectopedia. New York: Pantheon Books, 2010: 310.

Return to Reference.

22Rhys, Jean. The Collected Short Stories. New York: W.W. Norton, 1992: 92.

Return to Reference.

murmurations

it’s not our home this frame of wood dust glued with spit – the winter ladybugs swarm a house for warmth collected against the vinyl siding of the house they run muted red in the gutters – a swarm takes over suddenly – a movement in the corner of your brain turned live and shimmering – a gush of sound– the crawling bodies moving wings – a paper wasp enters a window screen osmotically – it crowds the edges of the skylight pushing in to build a chambered nest in caulk and tar – we rent our bones from blow flies – our eyes grow facets as they wait.

—Thera Webb

Know What Happened Last Year? A Hive of Bees Moved into My Mind. Bbzzzzz.

Water leaks into my bedroom & I watch the tide to see how high it gets how close to my bed before the sun takes it back before the picnic blanket sprawls dirtier & dirtier. In the flood I save a bureau, a box of papers, miscellaneous socks, a vintage accordion. I do not save the ants, the ants whose trail I stand over every morning to look in the mirror, my legs spread on either side of their diligent path, in any season. The ants that bite me, that sleep in the clothes I neglect to fold, that swarm any crumb that falls to the floor. Is what I’ve done. Have given death.

The palmetto bug I squished in your shower as your father faded in a dark study. Water by slow spoonfuls & applesauce. Blue feet. I’ve never had a brain growing inside my “belly.” Are there ever even humans?

I’ve killed indoor spiders. I’ve killed ants by accident. I’ve killed a parakeet with moldy rice when I had pneumonia. I’ve killed a career in journalism. I’ve killed the impulse to retreat. I’ve killed maggots (boiled to death in chicken broth). I’ve killed an 18 yr old dog that was about to die. I’ve killed Miller moths (got paid .25 cents per moth). I’ve killed miscellaneous bugs with the bumper of my speeding car. I’ve killed femininity with a neutral nickname & shorn hair. I’ve killed my father’s spider plant. I’ve killed a relationship with disgust of flared nostrils & fear of sex. I’ve killed mosquitoes everywhere I could. I feel responsible for any dead humming bird I find. The hobby of beauty.

In all of our knees, in all of our planning have we accounted for feelings & how to relay them? I’m embarrassed by how hard I try to live.

Numbers have no end but I do—a river running through the bedroom my bed the floor of the river. On porcelain, blood has never looked better.

No, I have not given life.

Have taken lives when they annoyed me.

Have made up some poems for you, drying in the yard. Made of images & those images of feelings so have I given you feelings & my bees have my bees given you beethoughts & how does the bzzz make the feeling & thoughts mash up like two clouds on the dance floor. What beeflood. What deranged murmur.

A fiery poem to heat the shore for ships? A calcified poem to steady your gate? A muscular poem, lifting boxes on moving day? What watery poem can save this plant? No, poems do not work like this.

The poem is a ceiling fan. Is a porch. A lawn. No, you are. Blood & it takes 10 days to notice the absence of ants. The slippers sprawled on the floor, no ants. Jeans piled under the bureau, directly in an empty path, no ants. Who will hear my bbzzzzing as I stand above & who will hold my wrists as my sound ceases. Like a bed made of cinnamon.

—Julia Cohen

N-sect Poetics

—Law Alsobrook