may

gold bodied dragonfly God bloodied you good my knuckles are sunburnt but not brass in the water I must close my mouth you hover in my ear like a heart the hummingbird weighs less than two copper pennies hold it down til it drowns little wish sunshine throw me off again in shame

—Beth Bachmann

Insects Are Food for Thought

In Persian, whenever I hear or think of the word حشره I immediately add to it the word مزاحم, as if “insect” cannot not be “intrusive, annoying.” The English noun doesn’t bring with it the same adjective as company.

Are ants insects?

Dumb question. Google it. Check Wikipedia. What kind of education did you get in school?

Of course they are. I know. But they seem to be of a totally different genre. Their life, life-work/work-life, is majestically mysterious. You can sit and watch for hours. Their patience. Their endurance. Their elegance. Their silence.

The childhood house had cockroaches. It was an old mansion. The cockroaches continued to be there even when the old black wooden kitchen cabinets were replaced by light-yellow metal ones. The adult cockroaches were disgusting. The baby ones scary, reminding you that cockroaches believed in reproduction for the survival of their species, believed in traditional family values.

Lizards are not insects, but now that we are in the childhood house kitchen, I want to pause for a moment and remember the beautiful lizards who sat there on the uneven large black stones of the stove chimney, posing for us while memorizing our food.

Humans in a sports stadium. Humans in an outdoor musical festival. Humans in a political rally. Humans fleeing en mass from one conflict toward another. Humans stopped at borders, herded into camps, if only lucky. To points of view far away in the universe, humans could be insects, petite creatures doing their thing, perhaps worth studying, perhaps easily ignorable. To points of view right here on earth, humans could sometimes be even less than insects.

—Poupeh Missaghi

No Collective

Believing themselves to be quite progressive for their species, a group of ants gets together and decides to form a collective. They gather the necessary documentation, fill out all the proper information in the correct little boxes, get photos taken in the right size and dimensions and angle, and step precisely through every single hoop required of them to become an officially recognized collective.

Their application is denied, however, on the grounds that ants are an inherently collective species, and this designation would be redundant and downright unnecessary.

One ant is so upset by this verdict that it begins to cry, thereby forging a breach in the collective emotional unity of the group. This very breach, however, makes the officer falter, reconsider for a brief moment, entertain the possibility of a radical change of heart, but this very possibility of a change in the officer’s heart makes the ant’s tears dry up, which lands them all back at their original, inherently collective state, and that’s the end of that story.

—Sawako Nakayasu, from The Ants

Gryllacridadae, The Impoverished

let’s assume you’ve seen this critter—half of something or another—or you’ve heard its abdomen thumping against the ground like a foot breaking down a door or felt the flash of its wingspread, when threatened, like how a newly brandished gun makes palm-sized men, gods.

let’s assume you’ve heard this critter leads reclusive, which is to say insular, lives, secreting balms over everything that’s not theirs—that leaf, that glass cage, that gold grill, that color, that block, that body, that finger—they will rage over a thumb in their cage. they will draw blood.

let’s assume if their god scientist, tries to contain them, they will vault out of their glass. they aren’t there for god’s ill amusement. fuck the god that put them in this predicament in the first place. they’ll jump if injured, or if they are owed, and they are owed, or if they are broken and they are broken open by one stray nick on the lip of their coop, viscera surging from their center, they will pause and eat themselves first, take in the fat of their own delicious dying, denying others the revolting pleasure of their anguish.

—Airea D. Matthews

for Edges & Fray

//

To build within the space

of a thought. As it becomes

sound, shaped into series, as it

becomes sentence and series,

as it becomes. This sensory logic

transfusing into linguistic design

holds us from the inside-out.

//

I study the archival patterns carried across

lineages: the New Guinea ladder-web

spider, coddisflies, aquatic larva,

termitaries, the tropical hornet, the

solitary wasp, ancestral bees, the bird-

species who harvest the silk of insects, who

pull out their own body hairs and bind

them with silk.

//

Can a book be like this protective

shell? A dwelling-architecture that is

at once deceptively small and

enormous, housing a body (or bodies) capable of

the largest dream?

//

Architectures of intimacy—each an archive

of internal dreaming. A breathing

record of this logic: a hive for

traveling through.

//

I think of the organ-pipe

wasp who frames long mud flutes

to reside within. They are solitary

though sometimes females may build side-

by-side, sharing a common wall.

//

Laid side by side like these solitary

hives. Become a wasp nesting

the book, our ears pressed

against each sentence.

//

When the structure has reached us.

Open it, endlessly, over time through the body.

With no tools or other artifacts, with only

our hands.

//

A cohabitation opened through the act.

—Danielle Vogel

Archive

enclose the burring beetle

enclose the flour moth

its white-mouth overdose and hereafter

enclose the white, the wet whites

of eyes or cocoon thread or the arctic

blank of projector-screen light

enclose the bone flutes and the percussive

devices, the delicate cranium now

light enough to build a hive in

enclose its leftover thoughts

nighttime carries an arc and hive

enclose any gold-touched ones

any that flicker, any called assassin

any with lace wings, nerve wings

enclose the field gone fanatical

with locusts, their victory pyrrhic

their pluranimity

enclose a report from an old catastrophe

enclose all the flying migrations

all the cross-atlantics

in hulls, in missile silos

in the deep sleep position for mars

enclose the one deep in a middle-of-nowhere

thought with beast roses and barbiturates

the mob of thoughts come to feast

on the cloth-night

enclose its peepholes, no one is ever

alone, mites live in your follicles

you glow in search-engine light

enclose the sent flowers made of pixels

you’re shamefaced, a little halo-faced

—Carolina Ebeid

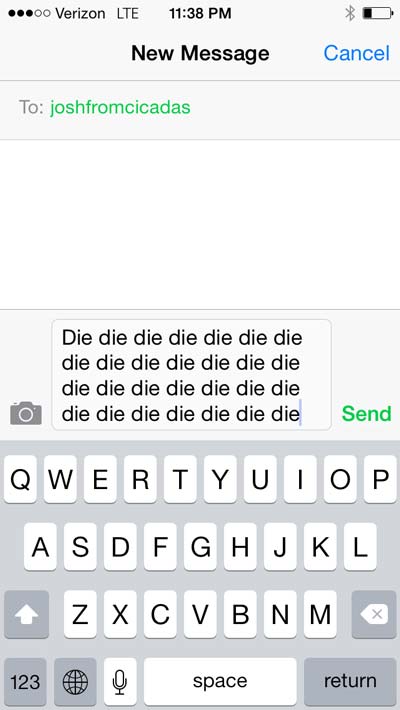

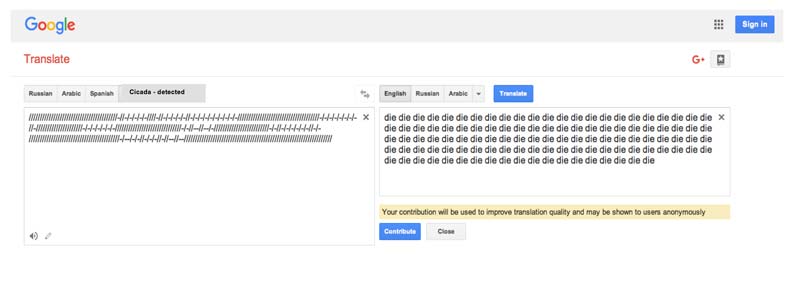

Cicadas (or, the problem of bodies / the problem of noise)

I.

Every July the cicadas came, vibrating the trees, singing the night, falling from the skies onto pavement, clogging gutters, littering walkways, piling up in streets and driveways.

They were relentless, the males, with their mating calls so loud they blocked out the usual summer noises: humming air-conditioning units, kids playing box-ball in the street past dark, parents’ cars turning into driveways late home from work.

When we rode bikes at dusk, our wheels would crunch over their bodies, their green eyes and green wing-veins, or just the empty golden shells of the almost-adults, called nymphs.

The Latin word “exuviae,” meaning “that which is stripped from a body,” is found only in the plural.

Our bodies—our bodies were lithe and leaned into the turns and coasted the hills—our bodies vibrated all summer.

The thing about poems is that they have bodies.

If you walked down the street and kicked at the black and green carcasses of the cicadas, sometimes a not-quite-dead one would rise up and shudder-buzz, and collapse again onto the warm asphalt.

II.

My brothers used to collect the shells in every available cup we had. I remember the sounds being calming.

Our dog would eat them. They’d continue to buzz in his mouth until he actually crunched his way through. I remember him sitting on the patio chomping away, and every once in a while he’d just have a wing hanging out of his mouth at a rakish angle.

And I remember always having a fear of kicking one of them away only to find it was still alive and in the process of dying where it would shudder and buzz for a second and go back to silence. I think I feared that liminal space.

I remember terrorizing a younger cousin by covering my clothing with the dried out shells (do you remember how they would cling onto fabric?) and chasing after him until he cried.

—Erika Meitner

(with special thanks to Margaret McCann, Devorah Adler, Margot Meitner, and Emily Dillof)

—Joshua Poteat

Cockroaches are thigmotropic. They feel pleasure, this term tells us, when all sides of their bodies, sides, top, bottom, back, are pressed against something. Crevices and cracks are places of pleasure to the cockroach. Maybe their antenna sticking out, forwardly, but otherwise—five of six—secure, sort of a travelling home, maybe even, to them, erotic. This is the reason we don’t see them. They’re off, being pleased. And when we do: suddenly! And: short-lived! Their horrible scurry is, in fact, the pursuit of pleasure or, same thing maybe, displeasure at the lack of pleasure. To us: horrible! And look at the entomologists, are they laughing at us? All entomologists must feel they live in another world but the cockroach entomologist especially, don’t we think? Yes, we do. What are they saying? “They’re thigmotropic, they scurry, it’s natural.” So our aversion is a prejudice to them. Yet here we are, the rest of the world, who say everyone, all, we. Fear of roaches is innate, we say. Darwin, filth, etc., etc. You entomologists, you roaches, are what’s unnatural. And look there! Such a lovely feeling when a concept like the “innate” settles around us. All our sides are pressed by its firmness. What a pleasure is fixity: things, behaviors, thoughts, governments. Maybe we won’t die. Maybe no one will call attention to us until we’re past this troubling time, out here in the open. We, the general, more like the object of the entomologist’s love than the entomologist. Are you jealous, entomologist? Firmness, pressingness, things and ideas backing us up, down, left, right, back. But then? This means? Well, it means the roach is us. Yes, we feared that. And that’s why, when they’re under the toaster, when one pops out of the flour, it’s like it is. My own severed hand is on the counter! My own eye has popped out of the flour! Ours! We! Everyone! Not here where we are but there where we aren’t. A thing like us! Anything to return, to get back, killing is honestly mild at that moment. It’s the lowest response we can think of. Why not? It pulled us out of us. And: we don’t like that.

—Brent Cunningham

DISTURBANCES

A soft bug from Gysinge, Sweden

Color Sketch, 1987

Cornelia Hesse-Honegger

What would have the meter surfaced around

it, shelled

Cornelia Hesse-Honegger is a scientific illustrator. She is known for her field studies of radiation-contaminated areas, a documentation of insects’ mutational disturbances. At publication there were of course scientists who opposed her premise of deviation, claiming that her bug-study amplified what is a normal rate of disturbance—that her inferred assembly between natural cycles and human interruption was groundless. The soft bug, however, lives to corrugate this binary. This binary, the soft bug asserts from its disaster ground, is maybe another form disturbed (retained) by contamination. This binary, the soft bug shows us, is a permeation in degrees. There is a form that is an extension of our trouble bodies. But the disturbance intervenes when the stanza infers a fallout that is not legible, our honey, squashed, surfaced. A landscape permeated. Cicadas wake up late.

Maybe now we encounter it in perma-dormancy, a casing

of a former form, “prototypes of a future nature” we look back on

Early morning nihilism: the charmed late summer vines dragging over the river, southern breezes, the marshes deep in their supermoon tides, Indian Point Energy Center feeding into the boroughs. Cicadas wake up late. There are few concepts too fluid to inhabit the present long enough to dip and roll over the waves, above the transparency of the surface. Deep in the cicada noise, their electricity whirs in fits, the boroughs whir in fits. In the parking lot I stand over its casing, inscribed with my tendency to expand against the membrane along the train-line, into an intimacy. An intimacy that is inanimate. An inanimate dynamism, long-form in its disturbance. A living poem, which hatches generations, transgresses its own logic, documents our long-form disturbances. Sometimes, together, we look backward.

—Brooke. H. Ellsworth

A volatile chemical cocktail spreads through the air. Plague thoughts. Source of alarm. Labor. I find video of Fred Moten’s talk titled, “Blackness and Performance.” He says, “blackness is a pretty radical disruption of the idea of self or of individuation precisely insofar as it is always both more and less than one,” and my immediate thought is swarm. Think, “It looked like a demon.” Slander from the frogmouth of Darren Wilson. To be at once greater than, excess, “the hulking demon,” and less than, the “it.” More and less than one. The eusocial swarm, both infinitesimal and infinite. I feel this. I am anathema. An oxymoronic valuation of my life. I transmit through trophallaxis a message, I am small, overwhelmed by my own nothingness in contrast to the true nameless other mysteries. This is my creature-consciousness, from Rudolf Otto the Christian. From this exo-skin, this excised skull, these skeletal kin, I can only estimate myself in the vacuum of self-depreciation, my nullity. Am I insect? Forage? Build? Defense? Which do I perform? Can I recognize my nest mates? My salivary reservoir phagostimulates an entymologist zaddy with a thing for rare bugs. A synergy. I soldier up the days with effigies of white men in my mandibles. I’ve been thinking a lot about my life as a termite, how they weaken and tear down existing infrastructure, ingest it. I am sitting beneath the architecture of my own spit—a termite queen pheromonal and in complete control.

—Joey De Jesus

Death is like the insect

—Emily Dickinson